Higher empathy people appear to process music like a pleasurable proxy for a human encounter — in the brain regions for reward, social awareness and regulation of social emotions.

People with higher empathy differ from others in the way their brains process music, according to a study by researchers at Southern Methodist University, Dallas and UCLA.

The researchers found that compared to low empathy people, those with higher empathy process familiar music with greater involvement of the reward system of the brain, as well as in areas responsible for processing social information.

“High-empathy and low-empathy people share a lot in common when listening to music, including roughly equivalent involvement in the regions of the brain related to auditory, emotion, and sensory-motor processing,” said lead author Zachary Wallmark, an assistant professor in the SMU Meadows School of the Arts.

But there is at least one significant difference.

Highly empathic people process familiar music with greater involvement of the brain’s social circuitry, such as the areas activated when feeling empathy for others. They also seem to experience a greater degree of pleasure in listening, as indicated by increased activation of the reward system.

“This may indicate that music is being perceived weakly as a kind of social entity, as an imagined or virtual human presence,” Wallmark said.

Researchers in 2014 reported that about 20 percent of the population is highly empathic. These are people who are especially sensitive and respond strongly to social and emotional stimuli.

The SMU-UCLA study is the first to find evidence supporting a neural account of the music-empathy connection. Also, it is among the first to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to explore how empathy affects the way we perceive music.

The new study indicates that among higher-empathy people, at least, music is not solely a form of artistic expression.

“If music was not related to how we process the social world, then we likely would have seen no significant difference in the brain activation between high-empathy and low-empathy people,” said Wallmark, who is director of the MuSci Lab at SMU, an interdisciplinary research collective that studies — among other things — how music affects the brain.

“This tells us that over and above appreciating music as high art, music is about humans interacting with other humans and trying to understand and communicate with each other,” he said.

This may seem obvious.

“But in our culture we have a whole elaborate system of music education and music thinking that treats music as a sort of disembodied object of aesthetic contemplation,” Wallmark said. “In contrast, the results of our study help explain how music connects us to others. This could have implications for how we understand the function of music in our world, and possibly in our evolutionary past.”

The researchers reported their findings in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, in the article “Neurophysiological effects of trait empathy in music listening.”

The co-authors are Choi Deblieck, with the University of Leuven, Belgium, and Marco Iacoboni, UCLA. The research was carried out at the Ahmanson-Lovelace Brain Mapping Center at UCLA.

“The study shows on one hand the power of empathy in modulating music perception, a phenomenon that reminds us of the original roots of the concept of empathy — ‘feeling into’ a piece of art,” said senior author Marco Iacoboni, a neuroscientist at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior.

“On the other hand,” Iacoboni said, “the study shows the power of music in triggering the same complex social processes at work in the brain that are at play during human social interactions.”

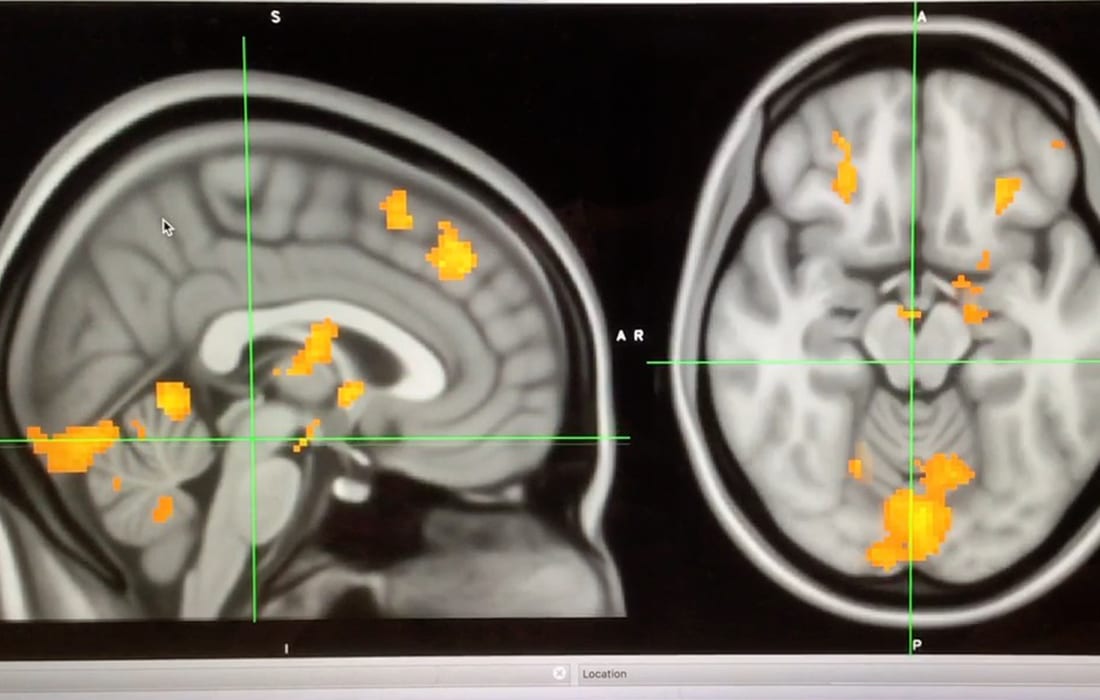

Comparison of brain scans showed distinctive differences based on empathy

Participants were 20 UCLA undergraduate students. They were each scanned in an MRI machine while listening to excerpts of music that were either familiar or unfamiliar to them, and that they either liked or disliked. The familiar music was selected by participants prior to the scan.

Afterward each person completed a standard questionnaire to assess individual differences in empathy — for example, frequently feeling sympathy for others in distress, or imagining oneself in another’s shoes.

The researchers then did controlled comparisons to see which areas of the brain during music listening are correlated with empathy.

Analysis of the brain scans showed that high empathizers experienced more activity in the dorsal striatum, part of the brain’s reward system, when listening to familiar music, whether they liked the music or not.

The reward system is related to pleasure and other positive emotions. Malfunction of the area can lead to addictive behaviors.

Empathic people process music with involvement of social cognitive circuitry

In addition, the brain scans of higher empathy people in the study also recorded greater activation in medial and lateral areas of the prefrontal cortex that are responsible for processing the social world, and in the temporoparietal junction, which is critical to analyzing and understanding others’ behaviors and intentions.

Typically, those areas of the brain are activated when people are interacting with, or thinking about, other people. Observing their correlation with empathy during music listening might indicate that music to these listeners functions as a proxy for a human encounter.

Beyond analysis of the brain scans, the researchers also looked at purely behavioral data — answers to a survey asking the listeners to rate the music afterward.

Those data also indicated that higher empathy people were more passionate in their musical likes and dislikes, such as showing a stronger preference for unfamiliar music.

Precise neurophysiological relationship between empathy and music is largely unexplored

A large body of research has focused on the cognitive neuroscience of empathy — how we understand and experience the thoughts and emotions of other people. Studies point to a number of areas of the prefrontal, insular, and cingulate cortices as being relevant to what brain scientists refer to as social cognition.

Studies have shown that activation of the social circuitry in the brain varies from individual to individual. People with more empathic personalities show increased activity in those areas when performing socially relevant tasks, including watching a needle penetrating skin, listening to non-verbal vocal sounds, observing emotional facial expressions, or seeing a loved one in pain.

In the field of music psychology, a number of recent studies have suggested that empathy is related to intensity of emotional responses to music, listening style, and musical preferences — for example, empathic people are more likely to enjoy sad music.

“This study contributes to a growing body of evidence,” Wallmark said, “that music processing may piggyback upon cognitive mechanisms that originally evolved to facilitate social interaction.” — Margaret Allen, SMU