Brian Stump, Albritton Professor of Earth Sciences in SMU’s Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences, has been elected chair of the board of directors for a university-based consortium that operates facilities for the acquisition, management and open distribution of seismic data.

The programs of the Incorporated Research Institutes for Seismology contribute to scholarly research, education, earthquake hazard mitigation and verification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. IRIS was founded in 1984 with support from the National Science Foundation: the late Eugene T. Herrin, Jr., who held the Shuler-Foscue Endowed Chair in SMU’s Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, was a founding member. IRIS facilities primarily are operated through its more than 100 member universities and in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey.

IRIS supports global seismic network, shares information, ideas, equipment

Scientists from member institutions participate in IRIS management through an elected nine-member board, eight regular committees and ad hoc advisory groups. Stump’s term of office as chair of the board is for three years, and will expire at the end of 2013.

“IRIS was formed because it was realized that we needed to support the global seismic network and needed the free exchange of information and ideas,” Stump said. “Instrumentation is so expensive that the seismic community needed to find a way to make equipment available to anyone who needs it for research, regardless of the size or funding capability of their parent institution.”

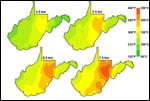

More than 4000 portable monitors are available through the IRIS PASSCAL facility at New Mexico Tech in Socorro, New Mexico. These instruments proved invaluable to Stump and his SMU team in researching a series of small earthquakes that occurred in North Texas between Oct. 30, 2008, and May 16, 2009. The ability to quickly place monitors at the site of the original quakes allowed scientists to record 11 earthquakes between Nov. 9, 2008, and Jan. 2, 2009, that were too small to be felt by area residents.

“The monitors available to IRIS members are well-used assets,” Stump said. “They’re constantly in service, like library books that fly off the shelves. We never have enough equipment.”

IRIS sponsors Stump as distinguished lecturer

Stump also is one of two distinguished lecturers sponsored this year by IRIS and the Seismology Society of America. One of his four scheduled talks on “Forensic Seismology and Nuclear Testing: The Detective Work of Seismologists” will be at 1:30 p.m. Jan. 29 at the Geology Museum at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J.

The Global Seismographic Network consists of more than 150 permanent stations around the world. It is operated by IRIS in cooperation with the USGS Geological Survey and allows seismologists to examine large events occurring anywhere to determine if they were caused by natural events such as earthquakes, or man-made events such as mine explosions or nuclear tests.

The connection between seismology and nuclear explosion monitoring began at the culmination of the Manhattan Project with the detonation of the first fission nuclear explosion in Southern New Mexico in July of 1945 and continues today with renewed discussions of ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. All of the data from the IRIS global and portable stations are archived at the IRIS Data Management Center in Seattle, Washington, and are freely and openly available on-line to researchers, educators and the public.

Stump research includes characterization of explosions

Brian Stump’s primary research interests include seismic wave propagation, seismic source theory and shallow geophysical site characterization. Recent work has focused on characterization of explosions as sources of seismic waves. Studies have included the quantification of single-fired nuclear and chemical explosions as well as millisecond-delay-fired explosions typical of those used in the mining industry. The spatial and temporal effects of mining explosions and their signature in regional waveforms have been of particular interest. This research has application to the monitoring of a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty where even small explosions will have to be identified using their seismic signatures.

Stump received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, where he held a UC Regents Intern Fellowship. Immediately following his graduate education he spent four years on active duty with the US Air Force as a staff seismologist and ultimately as Chief of the Geological Siting and Seismology Section. He joined the SMU faculty in 1983.

Stump joined the technical staff of the Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1994 to 1997, where he was program manager of the Nuclear Test Monitoring Group and participated in the negotiations for the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in Geneva, Switzerland, as a scientific advisor for the Department of Energy. He was a member of the team that received the Los Alamos National Laboratory Outstanding Performer Small Group Award in 1996. — Kim Cobb