Panic attacks that seem to strike sufferers out-of-the-blue are not without warning after all, according to new research.

A study based on 24-hour monitoring of panic sufferers while they went about their daily activities captured panic attacks as they happened and discovered waves of significant physiological instability for at least 60 minutes before patients’ awareness of the panic attacks, said psychologist Alicia E. Meuret at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

In a rare study in which patients were monitored around-the-clock, portable recorders captured changes in respiration, heart rate and other bodily functions, said Meuret, lead researcher on the study.

The new findings suggest sufferers of panic attacks may be highly sensitive to — but unaware of — an accumulating pattern of subtle physiological instabilities that occur before an attack, Meuret said.

Monitoring data also showed patients were hyperventilating on a chronic basis.

|

| Simulated panic sufferer and monitoring equipment. (Photo: SMU) |

“The results were just amazing,” Meuret said. “We found that in this hour preceding naturally occurring panic attacks, there was a lot of physiological instability. These significant physiological instabilities were not present during other times when the patient wasn’t about to have a panic attack.”

It is notable that patients reported the attacks as unexpected, lacking awareness of either the coming attack or their changing physiology.

“The changes don’t seem to enter the patient’s awareness,” Meuret said. “What they report is what happens at the end of the 60 minutes — that they’re having an out-of-the blue panic attack with a lot of intense physical sensations. We had expected the majority of the physiological activation would occur during and following the onset of the panic attack. But what we actually found was very little additional physiological change at that time.”

Unexpected attacks have been a mystery; little research to explain them

The diagnostic standard for psychological disorders, the DSM-IV, defines panic attacks as either expected or unexpected.

Those that are expected, or cued, occur when a patient feels an attack is likely, such as in closed spaces, while driving or in a crowded place.

“But in an unexpected panic attack, the patient reports the attack to occur out-of-the-blue,” Meuret said. “They would say they were sitting watching TV when they were suddenly hit by a rush of symptoms, and there wasn’t anything that made it predictable.”

To sufferers and researchers alike, the attacks are a mystery.

Change-point analysis uncovered physiological instabilities one hour before attacks

Meuret and her colleagues discovered the significant physiological instabilities using change-point analysis, a statistical method that searches for points when changes occur in a “process” over time.

“This analysis allowed us to search through patients’ physiological data recorded in the hour before the onset of their panic attacks to determine if there were points at which the signals changed significantly,” said psychologist David Rosenfield of SMU, lead statistician on the project.

The study is significant not only for panic disorder, but also for other medical problems where symptoms and events have seemingly “out-of-the blue” onsets, such as seizures, strokes and even manic episodes.

“I think this method and study will ultimately help detect what’s going on before these unexpected events and help determine how to prevent them,” Meuret said. “If we know what’s happening before the event, it’s easier to treat it.”

Meuret, an assistant professor in the SMU Department of Psychology, reported the results in the journal Biological Psychiatry in the article “Do Unexpected Panic Attacks Occur Spontaneously?” Rosenfield is an associate professor in SMU’s Department of Psychology.

A multi-disciplinary collaboration, other authors on the study were psychologist Thomas Ritz, SMU Department of Psychology; psychologist Frank H. Wilhelm, University of Salzburg, Austria; electrical engineer Enlu Zhou, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and psychologist Ansgar Conrad and psychiatrist Walton T. Roth, both of Stanford University.

Meuret discusses the research in an SMU Research youtube video.

Subtle physical changes impact panic sufferers more severely

People with panic disorder probably won’t be surprised by the results, Meuret said.

By definition, the majority of the 13 symptoms of panic attack are physiological: shortness of breath, heart racing, dizziness, chest pain, sweating, hot flashes, trembling, choking, nausea and numbness. Only three are psychological: feeling of unreality, fear of losing control and fear of dying.

“Most patients obviously feel that there must be something going on physically,” Meuret said. “They worry they’re having a heart attack, suffocating or going to pass out. Our data doesn’t indicate there’s something inherently wrong with them physically, neither when they are at rest nor during panic. The fluctuations that we discovered are not extreme; they are subtle. But they seem to build up and may result in a notion that something catastrophic is going on.”

Notably, the researchers found that patients’ carbon dioxide, or C02, levels were in an abnormally low range, indicating the patients were chronically hyperventilating. These levels rose significantly shortly before panic onset and correlated with reports of anxiety, fear of dying and chest pain.

“It has been speculated, but never verified with data recordings in daily life, that increases in CO2 cause feelings of suffocation and can be panic triggers,” Meuret said.

Fanny pack monitor tracked physiological changes before, during and after attacks

To capture the physiological data, 43 patients wore the monitoring devices for 24 hours on two separate occasions. The researchers collected 1,960 hours of ambulatory monitoring data, including 13 unexpected panic attacks.

Participants, all of whom suffer from panic disorder, were each outfitted with an array of electrodes and sensors attached to various parts of their bodies.

The ambulatory monitoring device was toted in a small waist pack the patients wore. Also included was a portable capnometer to measure CO2 collected from exhaled breath. The physiological responses were recorded continuously as digital data in a time series.

Each monitoring pack included a “panic button.” Patients were instructed to press the button if they had an attack and to write down their symptoms. By triggering the panic button, patients inserted a marker into the time-series data, marking the moment the attack began.

The sensors measured eight physiological indices, including changes in respiration, such as how deep, fast or irregular people were breathing; cardiac activity; and evidence of sweating.

Data analysis found strikingly significant changes in the hour before attacks

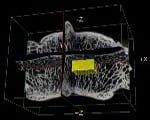

From the nearly 2,000 hours of data, the change-point analysis program allowed the researchers to slice out 70-minute periods around each of the 13 panic attacks — from one hour before onset until 10 minutes after the attacks began.

For each index, the program checked for any significant change in the signal that remained stable over a specified period of time.

Those results were collapsed across all 13 panic attacks, with minute-by-minute averages. The information was then compared to a 70-minute control period randomly chosen during non-panic periods.

“We found 15 subtle but significant changes an hour before the onset of the panic attacks that followed a logical physiological pattern. These weren’t present during the non-panic period,” Meuret said.

“Why they occurred, we don’t know. We also can’t say necessarily they were causal for the panic attacks. But the changes were strikingly and significantly different to what was observed in the non-panic control period,” she said.

Findings prompt look at “panic” definition and treatment

The study’s results invite a reconsideration of the DSM diagnostic definition that separates “expected” from “unexpected” attacks, Meuret said.

Also, the study might explain why medication or interventions aimed at normalizing respiration for treating panic are effective, she said. Medication generally buffers arousal, keeping it low and regular, thereby preventing unexpected panic attacks.

For psychological treatments such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), the results are more challenging. CBT requires a patient to focus on examining thoughts to prevent an attack.

“But a patient can’t work on something they don’t know is going to happen,” Meuret said.

New methodology can be universalized to other unexpected medical problems

The study’s use of change-point analysis can be applied to other medical issues. Traditional statistics are ineffective at analyzing such data, Meuret said, because they look only at level differences at pre-determined times and won’t find a signal for an unknown point.

“This study is a step toward more understanding and hopefully opening more doors for research on medical events that are difficult to predict. The hope is that we can then translate these findings into new therapies,” she said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health, Department of Veterans Affairs and the Beth and Russell Siegelman Foundation. — Margaret Allen

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.