At 10 p.m. on a Saturday night in April, a handful of SMU scientists continue working at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, called by its acronym CERN, in Geneva, Switzerland. A scattering of lights illuminates the windows in several buildings along the Rue Einstein, where researchers from dozens of countries and hundreds of institutions are combining their expertise on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) — the biggest physics experiment in history.

Ryszard Stroynowski, chair and professor of physics at SMU, points out each building in succession to a group of visitors. “By October, every light in every one of these windows will be on all night,” he says.

By then, the LHC is expected to be fully tested and ready to work. When the largest particle accelerator ever constructed becomes fully operational, it will hurl protons at one another with precision to a fraction of a micron and with velocities approaching the speed of light. These conditions will allow physicists to recreate and record conditions at the origin of the universe — and possibly discover the mechanisms that cause particles in space to acquire their differences in mass.

For Stroynowski, who has worked for almost 20 years to help make the experiment a reality, words seem inadequate to capture the anticipation surrounding its imminent activation.

“It is somewhat like that of a 6-year-old kid on Christmas Eve, waiting for Santa Claus,” he says. “The time stretches almost unbearably long.”

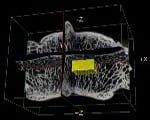

The LHC will be the site of several experiments in high-energy physics with high-profile collaborators such as Harvard and Duke and national laboratories including Argonne, Brookhaven, Lawrence Berkeley and Fermilab. None of the experiments is more imposing than ATLAS, one of two general-purpose particle detectors in the LHC array. At about 42 meters long and weighing 7,000 tons, ATLAS fills a 12-story cavern beneath the CERN facilities in Meyrin, Switzerland, just outside Geneva. It is a tight fit: ATLAS overwhelms even the vast space it occupies. A catwalk, not quite wide enough for two people to stand side by side, encircles the device and allows an occasional dizzying view into its works.

Size Matters

The detector’s scale will help to focus and release the maximum amount of energy from each subatomic collision. A series of bar codes on each of its parts ensure that the detector’s components, whether palm-sized or room-sized, are aligned and locked with the perfect precision required for operability. Scientists from 37 countries and regions and 167 institutions participated in its design and construction.

As U.S. coordinator for the literal and experimental heart of the ATLAS detector — its Liquid Argon Calorimeter — Stroynowski is helping to finalize the last details of the detector’s operation in anticipation of the extensive testing, scheduled to begin in August. He leads an SMU delegation that includes Fredrick Olness, professor, and Robert Kehoe and Jingbo Ye, assistant professors in the SMU Department of Physics in Dedman College.

SMU scientists are completing work on the computer software interfaces that will control the device, which measures energy deposited by the flying debris of smashed atoms. A cadre of University graduate students and postdoctoral fellows also is working on data processing for ATLAS’ 220,000 channels of electronic signals, an information stream larger than the Internet traffic of a small country.

An estimated 53,000 visitors crowded the CERN facilities on the organization’s “Day of Open Doors” April 6, eager for a glimpse of the work that CNN International has named one of the “Seven Wonders of the Modern World.”

At the beginning of May, the areas were sealed off in preparation for the first round of testing. Computers will remotely control the ATLAS experiment, which will not be touched by human hands because of the radiation released by the atomic collisions. Safety is the reason for the elaborate lockdown procedure involving more than 80 keys, each coded to a different individual’s biometric data. The system is designed to lock out any use of the device if even one key is unaccounted for.

“ATLAS has been built to run for at least 15 years with no direct human intervention,” Stroynowski says. “It will be as if we have shot it into space.”

Currently, the initial test run is scheduled to begin Sept. 1.

The Waiting Game

Once data start streaming in, the game of expectations management begins. The ATLAS detector will produce a staggering amount of raw information from each collision, and the most useful bits will be few and far between. Out of 40 million events per second, the researchers hope to pinpoint 10 events a year. The challenge seems a little like looking for a needle in a haystack the size of Mars.

“We may get what we’re looking for on the first try, or it may take us three years to find anything we can use,” Stroynowski says. “A big part of our job is to make sure we’re ready when we do.”

Among those entrusted with that task are graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in SMU’s Physics Department, including Rozmin Daya, Kamile Dindar, Ana Firan, Daniel Goldin, Haleh Hadavand, Julia Hoffman, Yuriy Ilchenko, Renat Ishmukhametov, David Joffe, Azeddine Kasmi, Zhihua Liang, Peter Renkel, Ryan Rios and Pavel Zarzhitsky.

“I came to SMU for postdoctoral work specifically because of the department’s involvement in the ATLAS project,” says David Joffe, a native of Canada who received his Ph.D. in physics from Northwestern University. “For particle physicists, being part of this is really a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

For Julia Hoffman, who received her doctorate from Soltans Institute for Nuclear Studies in her native Poland, that opportunity has meant expanding her own horizons.

“I learn new, and I mean really new, things every day,” she says. “Different programming languages, different views on physics analysis. I’m learning how it all works from the inside. I work with students and gain new responsibilities. This kind of experience means better chances to find a permanent position that will be as exciting as this one.”

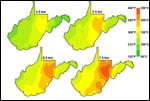

The SMU group works with formulae based in Monte Carlo methods, the “probabilistic models that use repeated random sampling of vast quantities of numbers” to impose a semblance of order on the chaos created when atoms forcibly disintegrate. Results are highly detailed simulations of known physics that will help make visible the tiny deviations researchers hope to detect when ATLAS begins taking data.

These unprecedented computing challenges also have become an impetus for new SMU research initiatives. James Quick, SMU associate vice president for research and dean of graduate studies, hopes to contain ATLAS’ vast data-processing requirements with a large-capability computing center located on campus.

Quick visited CERN in April to discuss the details with Stroynowski and other key personnel. The proposed center would provide a first-priority data processing infrastructure for SMU physicists and a powerful new resource for researchers in other schools and departments. During the inevitable LHC downtime, as beams are calibrated and software is debugged, the SMU center’s computing power would be available for campus researchers in every field across engineering, the sciences and business.

“The ATLAS experiment presents an opportunity for the University to step up in a big way, and one that will benefit the entire campus,” Quick says.

He envisions a data processing farm of 1,000 central processing units, each connected to an Internet backbone to allow the fastest possible return on SMU’s ATLAS input. Speed and access are the keys, Stroynowski says, paraphrasing Winston Churchill: “The winner gets the oyster, and the runner-up gets the shell.”

Those who have made their careers in high-energy physics are well aware of the stakes involved in the LHC, he adds, and being the first to process certain data could separate a potential Nobel Prize winner from those who will make the same discovery a day late.

As a group, high-energy physicists are accustomed to taking the long view — and for SMU researchers, the long view has been especially helpful. The ghost of the Superconducting Super Collider, which would have made its home in North Texas, still shadows the recent triumphs at CERN.

The SSC brought Stroynowski to the University, and its 1993 demise through congressional defunding was the impetus for the LHC project. The questions haven’t gone away because the experiment has changed venues, Stroynowski says. Yet even now, as the first test nears, his anticipation is tempered by caution.

“I don’t think we’ll get a beam all the way around [the LHC tunnel] on the first try,” he says.

Indeed, the subject of whether scientists will achieve a beam collision during the first tests or after additional calibration has been the subject of a few lively wagers.

“I think we’ll have to wait at least a few more weeks for that milestone,” he adds. “But in this case, I’ll be more than happy to be wrong.” — Kathleen Tibbetts

SMU has an uplink facility on campus for live TV, radio or online interviews. To speak with Dr. Biehl or Dr. D’Mello or to book them in the SMU studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650 or UT Dallas Office of Media Relations at 972-883-4321.

SMU is a private university in Dallas where nearly 11,000 students benefit from the national opportunities and international reach of SMU’s seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.