CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and its experiments are back in action, now taking physics data for 2016 to get an improved understanding of fundamental physics.

Following its annual winter break, the most powerful collider in the world has been switched back on.

Geneva-based CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) — an accelerator complex and its experiments — has been fine-tuned using low-intensity beams and pilot proton collisions, and now the LHC and the experiments are ready to take an abundance of data.

The goal is to improve our understanding of fundamental physics, which ultimately in decades to come can drive innovation and inventions by researchers in other fields.

Scientists from SMU’s Department of Physics are among the several thousand physicists worldwide who contribute on the LHC research.

“All of us here hope that some of the early hints will be confirmed and an unexpected physics phenomenon will show up,” said Ryszard Stroynowski, SMU professor and a principal investigator on the LHC. “If something new does appear, we will try to contribute to the understanding of what it may be.”

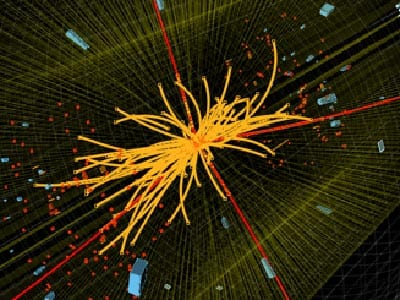

SMU physicists work on the LHC’s ATLAS experiment. Run 1 of the Large Hadron Collider made headlines in 2012 when scientists observed in the data a new fundamental particle, the Higgs boson. The collider was then paused for an extensive upgrade and came back much more powerful than before. As part of Run 2, physicists on the Large Hadron Collider’s experiments are analyzing new proton collision data to unravel the structure of the Higgs.

The Higgs was the last piece of the puzzle for the Standard Model — a theory that offers the best description of the known fundamental particles and the forces that govern them. In 2016 the ATLAS and CMS collaborations of the LHC will study this boson in depth.

Over the next three to four months there is a need to verify the measurements of the Higgs properties taken in 2015 at lower energies with less data, Stroynowski said.

“We also must check all hints of possible deviations from the Standard Model seen in the earlier data — whether they were real effects or just statistical fluctuations,” he said. “In the long term, over the next one to two years, we’ll pursue studies of the Higgs decays to heavy b quarks leading to the understanding of how one Higgs particle interacts with other Higgs particles.”

In addition, the connection between the Higgs Boson and the bottom quark is an important relationship that is well-described in the Standard Model but poorly understood by experiments, said Stephen Sekula, SMU associate professor. The SMU ATLAS group will continue work started last year to study the connection, Sekula said.

“We will be focused on measuring this relationship in both Standard Model and Beyond-the-Standard Model contexts,” he said.

SMU physicists also study Higgs-boson interactions with the most massive known particle, the top-quark, said Robert Kehoe, SMU associate professor.

“This interaction is also not well-understood,” Kehoe said. “Our group continues to focus on the first direct measurement of the strength of this interaction, which may reveal whether the Higgs mechanism of the Standard Model is truly fundamental.”

All those measurements are key goals in the ATLAS Run 2 and beyond physics program, Sekula said. In addition, none of the ultimate physics goals can be achieved without faultless operation of the complex ATLAS detector, its software and data acquisition system.

“The SMU group maintains work on operations, improvements and maintenance of two components of ATLAS — the Liquid Argon Calorimeter and data acquisition trigger,” Stroynowski said.

Intensity of the beam to increase, supplying six times more proton collisions

Following a short commissioning period, the LHC operators will now increase the intensity of the beams so that the machine produces a larger number of collisions.

“The LHC is running extremely well,” said CERN Director for Accelerators and Technology, Frédérick Bordry. “We now have an ambitious goal for 2016, as we plan to deliver around six times more data than in 2015.”

The LHC’s collisions produce subatomic fireballs of energy, which morph into the fundamental building blocks of matter. The four particle detectors located on the LHC’s ring allow scientists to record and study the properties of these building blocks and look for new fundamental particles and forces.

This is the second year the LHC will run at a collision energy of 13 TeV. During the first phase of Run 2 in 2015, operators mastered steering the accelerator at this new higher energy by gradually increasing the intensity of the beams.

“The restart of the LHC always brings with it great emotion”, said Fabiola Gianotti, CERN Director General. “With the 2016 data the experiments will be able to perform improved measurements of the Higgs boson and other known particles and phenomena, and look for new physics with an increased discovery potential.”

New exploration can begin at higher energy, with much more data

Beams are made of “trains” of bunches, each containing around 100 billion protons, moving at almost the speed of light around the 27-kilometre ring of the LHC. These bunch trains circulate in opposite directions and cross each other at the center of experiments. Last year, operators increased the number of proton bunches up to 2,244 per beam, spaced at intervals of 25 nanoseconds. These enabled the ATLAS and CMS collaborations to study data from about 400 million million proton–proton collisions. In 2016 operators will increase the number of particles circulating in the machine and the squeezing of the beams in the collision regions. The LHC will generate up to 1 billion collisions per second in the experiments.

“In 2015 we opened the doors to a completely new landscape with unprecedented energy. Now we can begin to explore this landscape in depth,” said CERN Director for Research and Computing Eckhard Elsen.

Between 2010 and 2013 the LHC produced proton-proton collisions with 8 Tera-electronvolts of energy. In the spring of 2015, after a two-year shutdown, LHC operators ramped up the collision energy to 13 TeV. This increase in energy enables scientists to explore a new realm of physics that was previously inaccessible. Run II collisions also produce Higgs bosons — the groundbreaking particle discovered in LHC Run I — 25 percent faster than Run I collisions and increase the chances of finding new massive particles by more than 40 percent.

But there are still several questions that remain unanswered by the Standard Model, such as why nature prefers matter to antimatter, and what dark matter consists of, despite it potentially making up one quarter of our universe.

The huge amounts of data from the 2016 LHC run will enable physicists to challenge these and many other questions, to probe the Standard Model further and to possibly find clues about the physics that lies beyond it.

The physics run with protons will last six months. The machine will then be set up for a four-week run colliding protons with lead ions.

“We’re proud to support more than a thousand U.S. scientists and engineers who play integral parts in operating the detectors, analyzing the data, and developing tools and technologies to upgrade the LHC’s performance in this international endeavor,” said Jim Siegrist, Associate Director of Science for High Energy Physics in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. “The LHC is the only place in the world where this kind of research can be performed, and we are a fully committed partner on the LHC experiments and the future development of the collider itself.”

The four largest LHC experimental collaborations, ALICE, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb, now start to collect and analyze the 2016 data. Their broad physics program will be complemented by the measurements of three smaller experiments — TOTEM, LHCf and MoEDAL — which focus with enhanced sensitivity on specific features of proton collisions. — SMU, CERN and Fermilab

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks

Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse

Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health

Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach

Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach Musicians who learn a new melody demonstrate enhanced skill after a night’s sleep

Musicians who learn a new melody demonstrate enhanced skill after a night’s sleep Study finds that newlyweds who are satisfied with marriage are more likely to gain weight

Study finds that newlyweds who are satisfied with marriage are more likely to gain weight Fruit flies fed organic diets are healthier than flies fed nonorganic diets, study finds

Fruit flies fed organic diets are healthier than flies fed nonorganic diets, study finds Center for Creative Leadership to study innovative learning method of SMU Lyle School of Engineering

Center for Creative Leadership to study innovative learning method of SMU Lyle School of Engineering NOvA neutrino detector in Minnesota records first 3-D particle tracks in search to understand universe

NOvA neutrino detector in Minnesota records first 3-D particle tracks in search to understand universe Parenting program tackles child abuse and neglect among formerly homeless families

Parenting program tackles child abuse and neglect among formerly homeless families Hiding in plain sight: How invisibility saved New Mexico’s Jicarilla Apache

Hiding in plain sight: How invisibility saved New Mexico’s Jicarilla Apache Study: Most Texas ISDs that are teaching the Bible are skirting 2007 state law

Study: Most Texas ISDs that are teaching the Bible are skirting 2007 state law

Dallas Observer: Physicists Near Discovery of God Particle

Dallas Observer: Physicists Near Discovery of God Particle

Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance

Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance Moving 3D computer model of key human protein is powerful new tool in fight against cancer

Moving 3D computer model of key human protein is powerful new tool in fight against cancer Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual

Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual Middle school boys who are reluctant readers value reading more after using e-readers

Middle school boys who are reluctant readers value reading more after using e-readers