The Congo Basin — with its massive, lush tropical rain forest — was far different 150 million to 200 million years ago.

At that time Africa and South America were part of the single continent Gondwana. The Congo Basin was arid, with a small amount of seasonal rainfall, and few bushes or trees populated the landscape, according to a new geochemical analysis of rare ancient soils.

The geochemical analysis provides new data for the Jurassic period, when very little is known about Central Africa’s paleoclimate, says Timothy S. Myers, a paleontology doctoral student in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at SMU.

“There aren’t a whole lot of terrestrial deposits from that time period preserved in Central Africa,” Myers says. “Scientists have been looking at Africa’s paleoclimate for some time, but data from this time period is unique.”

There are several reasons for the scarcity of deposits: Ongoing armed conflict makes it difficult and challenging to retrieve them; and the thick vegetation, a humid climate and continual erosion prevent the preservation of ancient deposits, which would safeguard clues to Africa’s paleoclimate.

Myers’ research is based on a core sample drilled by a syndicate interested in the oil and mineral deposits in the Congo Basin. Myers accessed the sample — drilled from a depth of more than 2 kilometers — from the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, where it is housed. With the permission of the museum, he analyzed pieces of the core at the SMU Huffington Department of Earth Science’s Isotope Laboratory.

“I would love to look at an outcrop in the Congo,” Myers says, “but I was happy to be able to do this.”

The Samba borehole, as it’s known, was drilled near the center of the Congo Basin. The Congo Basin today is a closed canopy tropical forest — the world’s second largest after the Amazon. It’s home to elephants, great apes, many species of birds and mammals, as well as the Congo River.

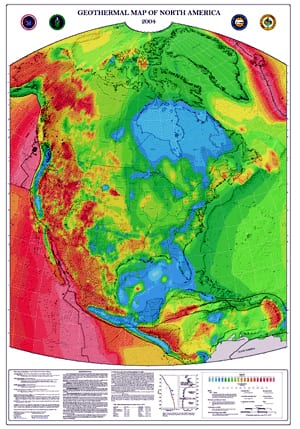

Myers’ results are consistent with data from other low paleolatitude, continental, Upper Jurassic deposits in Africa, and with regional projections of paleoclimate generated by general circulation models, he says.

“It provides a good context for the vertebrate fossils found in Central Africa,” Myers says. “At times, any indications of the paleoclimate are listed as an afterthought, because climate is more abstract. But it’s important because it yields data about the ecological conditions. Climate determines the plant communities, and not just how many, but also the diversity of plants.”

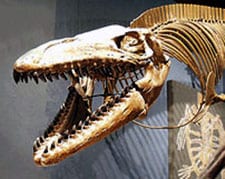

While there was no evidence of terrestrial vertebrates in the deposits Myers studied, dinosaurs were present in Africa at the same time. Their fossils appear in places that were once closer to the coast and probably wetter and more hospitable, he says.

The Belgium samples yielded good evidence of the paleoclimate. Myers found minerals indicative of an extremely arid climate typical of a marshy, saline environment. With the Congo Basin at the center of Gondwana, humid marine air from the coasts would have lost much of its moisture content by the time it reached the interior of the massive continent.

“There probably wouldn’t have been a whole lot of trees; more scrubby kinds of plants,” Myers says.

The clay minerals that form in soils have an isotopic composition related to that of the local rainfall and shallow groundwater. The difference in isotopic composition between these waters and the clay minerals is a function of surface temperature, he says. By measuring the oxygen and hydrogen isotopic values of the clays in the soils, researchers can estimate the temperature at which the clays formed.

Myers presented his research, “Late Jurassic Paleoclimate of Central Africa,” at a scientific session of the 2009 annual meeting of The Geological Society of America in Portland, Ore., Oct. 18-21. The research was funded by the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at SMU and SMU’s Institute for the Study of Earth and Man. — Margaret Allen

Polcyn is a world-recognized expert on the extinct marine reptile named

Polcyn is a world-recognized expert on the extinct marine reptile named