For paleobotanist Bonnie Jacobs standing atop a mountain in the highlands of northwest Ethiopia, it’s as if she can see forever — or at least as far back as 30 million years ago.

For paleobotanist Bonnie Jacobs standing atop a mountain in the highlands of northwest Ethiopia, it’s as if she can see forever — or at least as far back as 30 million years ago.

Jacobs is part of an international team of researchers hunting scientific clues to Africa’s prehistoric ecosystems.

The researchers are among the first to combine independent lines of evidence from various fossil and geochemical sources to reconstruct the prehistoric climate, landscape and ecosystems of Ethiopia in particular, and tropical Africa in general for the time interval from 65 million years ago — when dinosaurs went extinct, to about 8 million years ago — when apes split from humans.

|

|

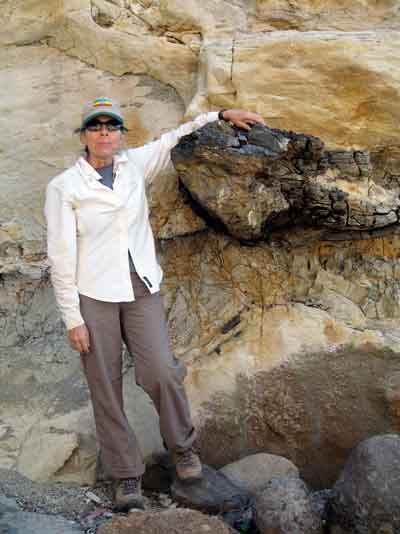

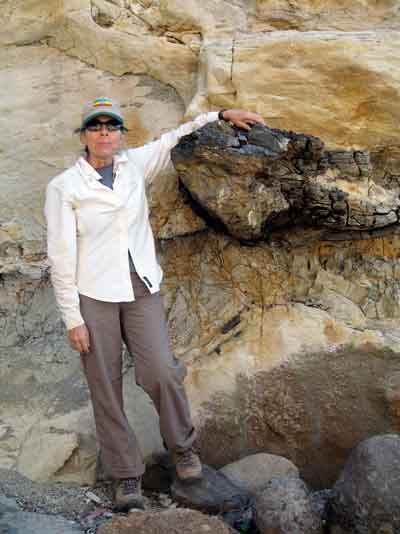

Paleobotanist Bonnie Jacobs in Ethiopia. |

While it’s generally held that human life began in Africa, ironically there is little known about changes in the continent’s vegetation during the time when humans were evolving.

The team’s work also will help climate scientists trying to model future global warming by providing data from the tropics that up to now did not exist.

The multi-disciplinary team is studying fossils they’ve found near Chilga, a small region in the agricultural highlands.

Contrary to the common notion that vegetation decomposes in the tropics too quickly to supply evidence, sediments there have preserved an abundant variety of 28 million-year-old fossils. These include fruits, seeds, leaves, woods, pollen and spores, says Jacobs, an associate professor of Earth Sciences at Southern Methodist University and director of the Environmental Science and Studies Programs.

“There are lifetimes of work to be done in Africa on plant fossils alone, and certainly a lot more to be done with vertebrates as well,” says Jacobs, who’s done research in Africa since 1980 in Kenya, Tanzania and Ethiopia. “There’s not a well established record of plant fossils, so there’s no real context. It’s all new — so whatever you find is interesting.”

With the permission of the Ethiopian government, Jacobs — along with Ellen Currano, in the Department of Geology at Miami University, and paleobotanist Aaron Pan, curator of science at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History — is now studying more than 1,600 fossil leaves the team gathered from two age-equivalent sites to understand climate, precipitation, vegetation and the physical landscape.

Jacobs is calculating precipitation and temperature estimates for the two Ethiopian sites using leaf traits for size and shape. While the rainfall estimates are statistically identical, the temperature estimates are not, an informative reflection of the method itself.

Pan has identified palm fossils, which help to address a big question about the timeframe for a decline in the presence of palm trees in Africa. He’s also calculating past climate using species composition of fossil leaves, fruit and flowers.

Currano is looking at insect damage on fossil leaves, to see if the insect fauna is as diverse and as specialized as expected for tropical forests. Neil Tabor, associate professor of Earth Sciences at SMU and an expert in sedimentology and isotope geochemistry, is calculating past climate using oxygen isotopes in minerals from fossil soils.

Currano is looking at insect damage on fossil leaves, to see if the insect fauna is as diverse and as specialized as expected for tropical forests. Neil Tabor, associate professor of Earth Sciences at SMU and an expert in sedimentology and isotope geochemistry, is calculating past climate using oxygen isotopes in minerals from fossil soils.

“We’re using multiple independent lines of evidence to get at climate reconstruction during this time interval for a place — the tropics of Africa — for which there were few data before,” Jacobs says. “The lower latitudes are especially poorly documented for fossils, which tell us about climate, so the tropical regions of Earth are poorly documented for past climate as well.”

The project is funded with a three-year, $322,000 grant from the National Science Foundation. Paleoanthropologists and vertebrate paleontologists from UT Austin, Washington University and the University of Michigan have studied the fossil bones that co-occur with the plants.

Questions they will address:

- When and how did Africa’s rain forests evolve into the present day savannas and how did that impact human evolution?

- What happened to the prehistoric lowland forest that’s been hypothesized across Africa in the tropical belt?

- When did the Great Rift Valley’s formation divide the forest into eastern and western components, and how did the process evolve?

- Why is there evidence of a large diversity of palm trees at 33 million years ago in Africa, but certain species are missing by 28 million years ago?

- Why were palm trees abundant and diverse 100 million years ago in Africa and South America, but now rare in present-day Africa, while still prolific in the tropical forests of Southeast Asia, South America and Madagascar?

Jacobs will present her research in October at a seminar on “Cenozoic Evolution of African Landscapes” at Penn State. She and other members of the team will also report on the Ethiopian fossils in a Geological Society of America Topical Session called “Phanerozoic Paleoenvironmental Evolution of Africa,” which they’ve organized for the annual meeting from Oct. 18-21.

Jacobs’ research today expands on earlier work. She reported with her collaborators at the 2008 “Celebrating the International Year of Planet Earth” meeting of the Geological Society of America that palm trees were significant in Africa 28 million years ago

In a 2006 study that published in the “Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society,” Jacobs and lead author Pan reported that Chilga fossil leaves represent the earliest records of Africa’s characteristic palm genus “Hyphaene.”

The leaf fossils that Jacobs, Currano, and Pan are cataloging will be permanently housed in a new building now under construction at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa.

With a $21,600 supplemental grant from the National Science Foundation, cabinets for storing the plant and vertebrate fossils have been made in Ethiopia and Jacobs, Currano and Pan will return later this year to curate the collections. — Margaret Allen

Related links:

Ethiopia project home page

Bonnie Jacobs

Bonnie Jacobs’ research

Neil Tabor

Ellen Currano

Why fossils matter

Bonnie Jacobs’ guide to finding fossils

SMU Student Adventures blog: Research team in Ethiopia, 2007-2008

Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences

Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences

Tabor’s research supplies a picture of the paleo landscape of Ethiopia that wasn’t previously known because the fossil record for the tropics has not been well established. The fossils were discovered in the grass-covered agricultural region known as Chilga, which was a forest in prehistoric times. Tabor’s research looked at soil fossils dating from 26.7 million to 32 million years ago.

Tabor’s research supplies a picture of the paleo landscape of Ethiopia that wasn’t previously known because the fossil record for the tropics has not been well established. The fossils were discovered in the grass-covered agricultural region known as Chilga, which was a forest in prehistoric times. Tabor’s research looked at soil fossils dating from 26.7 million to 32 million years ago. For paleobotanist

For paleobotanist

Currano is looking at insect damage on fossil leaves, to see if the insect fauna is as diverse and as specialized as expected for tropical forests.

Currano is looking at insect damage on fossil leaves, to see if the insect fauna is as diverse and as specialized as expected for tropical forests.

A team of researchers led by paleobotanist

A team of researchers led by paleobotanist