The business innovation magazine Fast Company took note of the SMU Geothermal Laboratory‘s recent report on the large green-energy geothermal resource underground in West Virginia. The research was funded by Google.org.

SMU geologist David Blackwell leads the lab and its research.

The Oct. 8 article “How Google Cash Helped Find Geothermal Energy in West Virginia” by reporter Ariel Schwartz notes that Google.org’s foray into geothermal is the latest step in its renewable energy investments.

EXCERPT:

By Ariel Schwartz

Fast Company

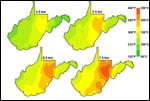

Google has already spent a lot of money on renewable energy investments. Now the search giant can be credited with bringing green energy to a state that mostly relies on coal-fired power. A project from Southern Methodist University, funded by a $481,500 grant from Google.org, has found that West Virginia has 78% more geothermal energy than previously estimated. That means the state could double its electrical generation capacity without bringing more coal power online.Now we know that West Virginia could produce up to 18,890 MW of clean energy if just two percent of its geothermal energy resources were used. The state currently has a generating capacity of 16,350 MW — and 97% of that comes from coal.

Journalist Robert Wilonsky at The Dallas Observer also covered the SMU Geothermal Lab’s release of the West Virginia mother lode of geothermal resource in his Oct. 7 Unfair Park entry: Hot Hot Heat: SMU Researchers Find West Virginia’s Just Leaking Geothermal Energy.

Wilonsky quotes Maria Richards, coordinator of the SMU Geothermal Laboratory, saying “they’ve discovered what could be enough Earth-made energy to potentially support ‘commercial baseload geothermal energy production.'”

EXCERPT:

By Robert Wilonsky

The Dallas Observer

At month’s end, researchers from SMU’s Geothermal Laboratory — among ’em, David Blackwell, Hamilton Professor of Geophysics and director of the SMU Geothermal Laboratory — will go to Sacramento for the 2010 Geothermal Resources Council annual meeting. There, the trio will present a much more detailed version of this report just posted to the Hilltop’s website, in which Blackwell, grad student Zachary Frone and geothermal expert Maria Richards say that in the western part of the Appalachian Mountains, they’ve discovered what could be enough Earth-made energy to potentially support “commercial baseload geothermal energy production.”

The international news wire service Reuters also covered the report’s release with a story by Danny Bradbury of GreenBiz.com: “Google Warms to West Virginia’s Vast Geothermal Potential.”

EXCERPT:

By Danny Bradbury

GreenBiz.com

A Google-funded project has discovered a large geothermal resource under West Virginia that could more than double the electrical generation capacity of the high-profile coal state.The research, carried out by the Southern Methodist University and funded with a $481,500 grant from Google’s philanthropic arm, found that there is 78 percent more geothermal energy under the state than originally estimated.

The researchers calculated that if 2 percent of the available geothermal energy could be harnessed, the state could produce up to 18,890 megawatts (MW) of clean energy.

The study was conducted with more detailed mapping and more data points than had been used in previous research. For example, 1,455 new thermal data points were added to existing geothermal maps using oil, gas and water wells.

The research team found that most of the high-temperature points are located in the eastern part of the state.

“The presence of a large, baseload, carbon-neutral and sustainable energy resource in West Virginia could make an important contribution to enhancing the U.S. energy security and for decreasing CO2 emissions,” the report concluded.

Other coverage:

- The Charleston Gazette: “SMU study shows West Virginia as a geothermal hot spot”

- Geothermal Energy: “It’s hot in West Virginia: Researchers discover 1,450 geothermal wells”

- Renewable Energy World: “New research suggests that West Virginia could be an East Coast leader in utility-scale geothermal”