Study by SMU, UT Austin and Stanford scientists rates faults for potential earthquakes; Faults under DFW urban area viewed as lower quake hazard

DALLAS (SMU) – Scientists from SMU, The University of Texas at Austin and Stanford University found that the majority of faults underlying the Fort Worth Basin are as sensitive to forces that could cause them to slip as those that have hosted earthquakes in the past.

The new study, published July 23rd by the journal Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America (BSSA), provides the most comprehensive fault information for the region to date.

Fault slip potential modeling explores two scenarios: a model based on subsurface stress on the faults prior to high-volume wastewater injection and a model of those forces reflecting increase in fluid pressure due to injection.

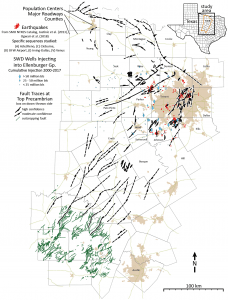

None of the faults shown to have the highest potential for an earthquake are located in the most populous Dallas-Fort Worth urban area or in the areas where there are currently many wastewater disposal wells.

Yet, the study also found that the majority of faults underlying the Fort Worth Basin are as sensitive to forces that could cause them to slip and cause an earthquake as those that have hosted earthquakes in recent years.

Though the majority of the faults identified on this map have not produced an earthquake, understanding why some faults have slipped and others with similar fault slip potential have not continues to be researched, said SMU seismologist and study co-author Heather DeShon, who has been the lead investigator of a series of other studies exploring the cause of the North Texas earthquakes.

Earthquakes were virtually unheard of in North Texas until slightly more than a decade ago. But more than 200 earthquakes have occurred in the region since late 2008, ranging in magnitude from 1.6 to 4.0. A series of studies have linked these events to the disposal of wastewater from oil and gas operations by injecting it deep into the earth at high volumes, triggering “dead” faults nearby.

A total of 251 faults have been identified in the Fort Worth Basin, but the researchers suspect that more exist that haven’t been identified.

The study found that the faults remained relatively stable if they were left undisturbed. However, wastewater injection sharply increased the chances of these faults slipping, if they weren’t managed properly.

“That means the whole system of faults is sensitive,” said the lead author of the study Peter L. Hennings, a research scientist from UT Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology and the principal investigator at the Center for Integrated Seismicity Research (CISR).

DeShon said the new study provides fundamental information regarding earthquake hazard to the Dallas-Fort Worth region.

“The SMU earthquake catalog and the Texas Seismic Network catalog provide necessary earthquake data for understanding faults active in Texas right now,” she said. “This study provides key information to allow the public, cities, state and federal governments and industry to understand potential hazard and design effective public policies, regulations and mitigation strategies.”

“Industrial activities can increase the probability of triggering earthquakes before they would happen naturally, but there are steps we can take to reduce that probability,” added co-author Jens-Erik Lund Snee, a doctoral student at Stanford University.

Earthquake rates, like wastewater injection volumes, have decreased significantly since a peak in 2012. But as long as earthquakes occur, earthquake hazard remains. Dallas-Fort Worth remains the highest risk region for earthquakes in Texas because of population density.

Even after the earthquakes died away, North Texas residents have wondered about the region’s vulnerability to future earthquakes – especially since no map was available to pinpoint the existence of all known faults in the region. The new data, while still incomplete, benefited from information gleaned from newly released reflection seismic data held by oil and gas companies, reanalysis of publicly available well logs, and geologic outcrop information.

U of T at Austin and Stanford University provided the fault data and calculated fault slip potential. SMU, meanwhile, has been tracking seismic activity — which measures when the earth shakes —since people in the Dallas-Fort Worth area felt the first tremors near DFW International Airport in 2008. A catalog of all those tremors was recently published in June in the journal BSSA.

SMU seismologists have also been the lead or co-authors of a series of studies on the North Texas earthquakes. SMU research showed that many of the Dallas-Fort Worth earthquakes were triggered by increases in pore pressure — the pressure of groundwater trapped within tiny spaces inside rocks in the subsurface. An independent study done by SMU’s seismologist Beatrice Magnani found that wastewater injection reactivated dormant faults near Dallas that had been dormant for the last 300 million years.

DeShon said any future plan to mine for oil or natural gas in Fort Worth basin should be done with an understanding that the basin contains several faults that are highly-sensitive to pore-pressure changes. The study noted that rates of injection dropped sharply in the Fort Worth basin, but the practice still continues. Most of the injection that has taken place has been concentrated in the Johnson, Tarrant, and Parker counties, near areas of continued seismic activity.

“The largest earthquake the Dallas-Fort Worth region experienced was a magnitude 4 in 2015” DeShon said. “The U.S. Geological Survey and Red Cross provide practical preparedness advice for your home and work places. Just as we prepare for tornado season in north Texas, it remains important for us to have a plan for experiencing earthquake shaking.”

Many outlets covered the news:

- Dallas Morning News

- NBC 5

- KRLD

- The Weather Channel

- OK Energy Today

- Science Codex

- Homeland Security Today

- Science Daily

- Scienmag

About SMU

SMU is the nationally ranked global research university in the dynamic city of Dallas. SMU’s alumni, faculty and nearly 12,000 students in seven degree-granting schools demonstrate an entrepreneurial spirit as they lead change in their professions, communities and the world.