A new study uses carbon isotope dating to determine the first precise age for this bed, and ties the western coast of Africa to 30 million years of global geologic records

Paleontologists at Southern Methodist University have measured the carbon isotopes in marine fossils to precisely date for the first time 30 million years of sediments along Africa’s South Atlantic shoreline.

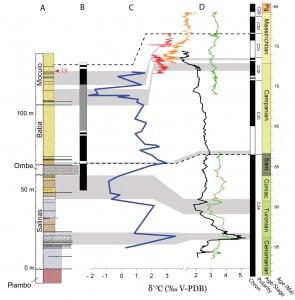

The researchers matched the pattern of ratios of carbon-13 and carbon-12 isotopes in marine fossils from Africa’s South Atlantic shoreline to known patterns of carbon ratios in fossils found elsewhere in the world. From that they determined the age of the coastal sediments at a fossil locality near the southern Angolan village of Bentiaba, said paleontologist Christopher Strganac, lead author on the study.

The analysis focused on a sequence of shoreline sediments totaling 140 meters thick. Their age spans a timeline of nearly 30 million years, from 95 million years ago to 68 million years ago. That period was about 40 million years after Africa and South America split, allowing the South Atlantic Ocean to slowly emerge.

The analysis revealed that the richest marine reptile fossil bed on Africa’s South Atlantic dated to 71.5 million years ago, he said. This new date at the Bentiaba locality is more than 2 million years older than the estimated date of about 69 million years previously assigned to those marine beds by earlier researchers.

Africa’s South Atlantic coast is remarkable in plate tectonics as the place where part of the prehistoric supercontinent Gondwana split 130 million years ago into what we now call Africa and South America.

“The precise age for these rocks allows better understanding of the ancient life and environments at Bentiaba by placing them accurately within the history of the ancient South Atlantic,” said Strganac, a doctoral student in SMU’s Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences. “It’s a benchmark now from the Southern Hemisphere with which we can better understand ancient life at that time.”

The precise dating was made possible by new scientific dating techniques. The age of the rocks hadn’t previously been assessed because Africa’s South Atlantic shore — noted for its puzzle-like fit with South America — has few localities with well-exposed rocks of this age. Also, it has been essentially unexplored by scientific expeditions since the 1960s largely because war and unrest prevented exploration in the previous century.

The new measurements stem from the work of Projecto PaleoAngola, an international team of scientists who in recent years have explored Angola and discovered an abundance of fossils. Their discoveries include the bones of dinosaurs, whales, mosasaurs and other ancient life from what is the richest marine reptile fossil bed along the South Atlantic coast.

Strganac and his co-authors report their findings in the Journal of African Earth Sciences. The article, “Carbon isotope stratigraphy, magnetostratigraphy, and 40Ar/39AR age of the Cretaceous South Atlantic coast, Namibe Basin, Angola,” is available online through open access at http://bit.ly/1v4r8xi.

“This improvement in understanding the ages of the rocks along the shore is a great first step in trying to understand the climatic and evolutionary events that accompanied the growth of this ocean,” said vertebrate paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs, also a co-author on the study and co-leader of Projecto PaleoAngola. Jacobs describes Angola as “an untapped frontier” for fossil hunters.

Aids in new knowledge of climate, temperature and vegetation

Scientists have recognized since the 1960s that ancient supercontinents split apart and their remnants drifted to the current positions of today’s continents over the course of millions of years. One of the results was the creation of vast new oceans. Little is known of the vertebrate life that lived during that time along the eastern and western margins of the emerging South Atlantic Ocean.

Fossils being discovered now by Projecto PaleoAngola hold the key to understanding the South Atlantic Ocean’s ancient past. Analysis of the fossils sheds light on the paleoenvironment, including changes in climate, temperature, vegetation and ecology.

The geologic time period covered by the 30-million-year sequence represents the Late Cretaceous. Studies have shown it was a period of dramatic change in climate, beginning with one of the warmest periods on Earth, then starting to transition to cooler climates, Strganac said.

Determining carbon ratios allowed comparison with global geologic events

To discover the age of the sediments, Strganac tested 55 fossil shells of ancient oysters and clams from 40 different rock layers on the coast. Testing determined the ratio of stable carbon isotopes, carbon-13 and carbon-12, in each shell. Because these isotopes do not decay with time, the relative abundance of each relates to the ocean when the shells formed. These isotope ratios can be compiled as a sequence with the rock layers, producing a pattern of carbon isotope change in the ancient oceans through millions of years. To accurately date the rocks, Strganac matched the pattern in isotope ratios in the shell record at Angola with the pattern known from ancient geologic events that occurred elsewhere in the world.

Specifically, the red rift-valley layers at Bentiaba were deposited as Africa and South America began to split. Also observed in the layers are a reversal in the Earth’s magnetic polarity at 71.4 million to 71.64 million years to delimit the age of marine fossils; rocks deposited in the South Atlantic Ocean 93.9 million years ago during an oceanic anoxic event; and rocks south of Bentiaba that bracket the mass extinction of dinosaurs at 66 million years.

Besides comparing the stable carbon isotopes, other measuring techniques included: magnetostratigraphy, which measures the ancient polarity of the Earth’s magnetic field when various sedimentary layers were deposited; and argon-argon radiometric dating of a volcanic basalt layer at the site, which measures the radioactive decay of potassium to argon and dates the cooling of the volcanic lava to 85 million years ago.

“Adding a new ocean to the globe, in this case the South Atlantic, has many long-lasting effects,” said SMU’s Jacobs. “One obvious example is the formation of energy resources found along the coasts of Brazil and Angola.”

The research was funded in part by the National Geographic Society and the Petroleum Research Fund of the American Chemical Society. — Margaret Allen

Follow SMUResearch.com on Twitter.

For more information, www.smuresearch.com.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Comet theory false; doesn’t explain cold snap at the end of the Ice Age, Clovis changes or mass animal extinction

Comet theory false; doesn’t explain cold snap at the end of the Ice Age, Clovis changes or mass animal extinction Real-time audio of corporal punishment shows kids misbehave within 10 minutes of spanking

Real-time audio of corporal punishment shows kids misbehave within 10 minutes of spanking Conventional vs. modern: Repertoire drives opera house identity, market share

Conventional vs. modern: Repertoire drives opera house identity, market share Women have made strides for equality in society, but gender gap still exists in art museum directorships

Women have made strides for equality in society, but gender gap still exists in art museum directorships Search for dark matter covers new ground with CDMS experiment in Minnesota

Search for dark matter covers new ground with CDMS experiment in Minnesota NOvA experiment glimpses neutrinos, one of nature’s most abundant, and elusive particles

NOvA experiment glimpses neutrinos, one of nature’s most abundant, and elusive particles SMU scientists to deploy seismic monitors in North Texas region near Azle, Texas

SMU scientists to deploy seismic monitors in North Texas region near Azle, Texas