SMU biologists tap supercomputer in fight against recurring cancer when chemotherapy fails

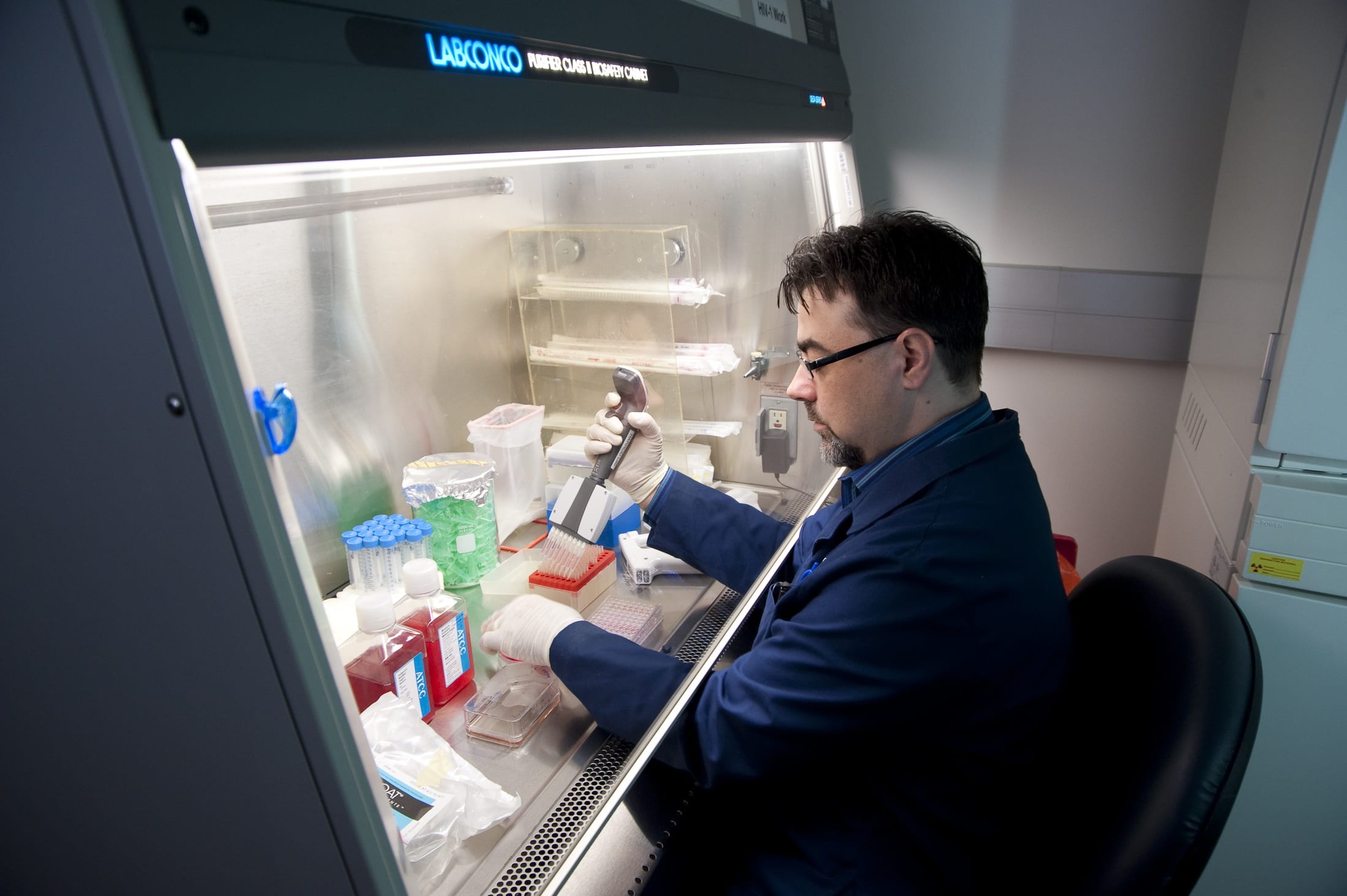

SMU biologists Pia Vogel and John Wise in the SMU Department of Biological Sciences are using the computational power of the SMU high-performance supercomputer to screen millions of drug compounds. They hope to find one that will aid in the fight against recurring cancer.

Vogel is an associate professor and director of SMU’s Center for Drug Discovery, Design and Delivery*. Wise is a research associate professor. Together they are seeking a compound that can be developed into a drug that re-enables chemotherapy when cancer recurs and chemotherapy appears no longer effective.

In the following interview, Vogel and Wise discuss their quest, made possible by the massive computational power supplied by supercomputers — a technique not possible even a decade ago.

Q: You’re searching for a cancer drug that provides hope for chemotherapy failure?

Vogel: Yes. Since the 1970s it’s been known that a sort of sump pump, the protein called P-glycoprotein, is most likely responsible for the failure of many chemotherapies — the drug is being pumped out of cancer cells by this sump pump that occurs naturally within all cells, even cancer cells.

Q: Tell us about P-glycoprotein.

Wise: This particular protein is one of nature’s great solutions to the problem of getting toxic things out of the cell. When a toxic substance enters a cell, the protein pumps it out.

This process may become a problem, however, once a cancer patient has been treated with chemotherapy, and appears to be cured.

If the cancer later returns, the cancer cells may express more P-glycoprotein than cells normally would. For that reason, chemotherapy is no longer effective because the protein considers it a “toxin” and pumps it out of the cells before the chemotherapy can destroy the cancerous cell.

Theoretically, if we can knock out the sump-pump proteins, then all those cancer chemotherapies that don’t work anymore, will work again.

Q: How does the sump pump work?

Wise: P-glycoprotein has a generic binding site for drugs. When the drug binds, that activates the part of the protein that uses the energy in ATP energy molecules by breaking the ATP down. This release of energy from ATP then moves the drug from one side of the protein to the other. It turns out that the “other side” of the protein is on the outside of the cell, so the drug has just been pumped out of the cell. The process takes only a fraction of a second and moves the drug from inside the cell, where it would kill the cancerous cell, to the outside where it is essentially harmless to the cancer.

So nature’s kind of outfoxing us here, because the pump has this beautiful generic toxin-binding site that allows the cells to survive. The downside is in cancer chemotherapy. Here the “toxin” is actually the drug we are hoping will kill the cancer and it will also be pumped out. So what we are doing is we’re looking for drugs that will temporarily inhibit the pump. What we’re hoping for is a new drug that stops the sump pump in the cancer cell so that the cancer chemotherapy can remain in the cell so it can kill the cancer.

Q: Tell us about the search.

Wise: Everything that lives has a version of this type of protein. So there are evolutionary connections between bacterial versions of this protein and the human versions. They all seem to work the same way, and are close in structure and function.

No one has actually determined the structure of the human P-glycoprotein directly. We don’t know what it looks like. Relying on these evolutionary relationships and with our understanding of how proteins are put together, I’ve deduced a structure of the human protein. We then use computer programs to model the protein in a way that brings the static picture of the human pump to life in the computer.

This is a very different tack than has been used historically in the field of protein structure biochemistry. Historically, proteins are very often viewed as static images, even though we know that in reality these proteins move and are dynamic.

Using simulation software (NAMD Molecular Dynamics, a freely downloadable software developed by researchers at the University of Illinois), we can physically build these molecules in the computer, in silico, and computationally we can model a variety of conditions: We can raise the temperature to 37 degrees centigrade, we can have the right pH, the right salts and all the right conditions, just like in a wet lab experiment. We can watch them thermally move and we can watch them relax.

The software is good enough that the model will relax and move according to the laws of physics and biochemistry. In this way we can see how these compounds interact with the protein in a dynamic way, not just in a snapshot way.

Q: How many screenings have you carried out on the supercomputer?

Wise: So far we’ve run about 8.8 million computational hours since August 2009, and screened roughly 8 million drugs. We are currently screening about 50,000 drugs per day on SMU’s High Performance Computer.

Vogel: We found a couple hundred compounds that were interesting, and so far we chose about 30 of those to screen in the lab. From those, we found a handful of compounds that do inhibit the protein. So we were very thrilled about that. Now we’re going back into the models that John has created and we’re looking for other compounds that might be able to throw a stick in the pump’s mechanism. We’re going at it in a selective way, so we don’t waste money with huge high-throughput screening assays in the lab.

Q: What have you learned so far?

Wise: This has been a good proof-of-principle. We’ve seen that running the compounds through the computational model is an effective way to rapidly and economically screen massive numbers of compounds to find a small number that can then be tested in the wet lab.

Q: Why is this kind of research possible now?

Wise: There have been huge increases in computational power in recent years. Ten years ago you couldn’t dock 8 million drugs — there just wasn’t enough computational power. Now SMU owns enough to do that.

Q: Has anyone else used the software in this way?

Wise: I don’t think anyone else has looked at 8 million drugs. And I’m almost positive that no one has looked at drug binding dynamically on that scale.

Q: How have you tested it in the lab?

Vogel: We use the purified protein itself and see whether those compounds really inhibit the power stroke, the ATP hydrolysis. We work with mouse protein, which is closely related to the human protein, but a little more stable.

Q: What’s the next step?

Vogel: We’ll collaborate with cell culture researchers here at SMU’s Center for Drug Discovery, Design and Delivery* and see if the compounds are toxic to cultured cancer cells and whether they will reverse chemo-resistance in some cell lines that we know do not respond to chemotherapeutics.

Wise: The ultimate goal of our research would be a compound that is safe and effective. To give an idea of the odds, out of a hundred good inhibitors that we might find, 95 of them might be extremely toxic and can’t be used. In the pharmaceutical industry, there are many, many candidates that fall by the wayside for one reason or another. They metabolize too quickly, or they’re too toxic, or they’re not soluble enough in the acceptable solvents for humans. There are many different reasons why a drug can fail. Finding a handful has been a great confirmation that we’re on the right track, but I would be totally amazed if one of the first we’ve tested was the one we’re looking for. — Margaret Allen

Although the department is small, a synergy has developed from building a faculty that is focused on cellular and molecular biochemistry, Orr says.

Although the department is small, a synergy has developed from building a faculty that is focused on cellular and molecular biochemistry, Orr says.