An international team of scientists, including Anthony Marks, professor emeritus at Southern Methodist Univeristy, have rejected the existing view that modern humans left Africa around 70,000 years ago. Their data reveal that humans left Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously suggested and were, in fact, present in eastern Arabia as early as 125,000 years ago.

These “anatomically modern” humans — you and me — had evolved in Africa about 200,000 years ago and subsequently populated the rest of the world.

The new study is “Did Modern Humans Travel Out of Africa Via Arabia?” It was published in the journal Science and reports findings from an eight-year archaeological excavation at Jebel Faya in the United Arab Emirates. The project, led by Hans-Peter Uerpmann from Eberhard-Karls-University, Tubingen, Germany, reached Palaeolithic levels in 2006.

Palaeolithic stone tools were technologically similar to tools from east Africa

SMU’s Marks and Vitaly Usik, National Academy of Sciences, Kiev, Ukraine, analyzed the Palaeolithic stone tools found at the site and discovered that they were technologically similar to tools produced by early modern humans in east Africa, but very different from those produced to the north, in the Levant and the mountains of Iran. This suggested that early modern humans migrated into Arabia directly from Africa and not via the Nile Valley and the Near East as is usually suggested.

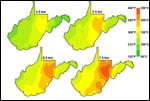

The direct route from east Africa to Jebel Faya crosses the southern Red Sea and the flat, waterless Nejd Plateau of the southern Arabian interior, both of which represent major obstacles to human migration. However, Adrian Parker, Oxford Brookes University, studied sea-level and climate change records for the region and concluded that the direct migration route may have been passable for brief periods in the past.

During Ice Ages, large amounts of water are stored on land as ice, causing global sea-levels to fall. At these times, the Bab al-Mandab seaway of the southern Red Sea narrows considerably, making it easier to cross.

Lower sea level made more direct route possible

Natural climate changes at the end of Ice Ages cause rainfall over the Nejd Plateau to increase, making the area habitable.

“By 130,000 years ago, sea-level was still about 100 meters lower than at present while the Nejd Plateau was already passable,” Parker said. “There was a brief period where modern humans may have been able to use the direct route from east Africa to Jebel Faya.”

Armitage calculated the age of the stone tools at Jebel Faya using a technique called luminescence dating. His ages revealed that modern humans were at Jebel Faya by around 125,000 years ago, immediately after the period in which the Bab al-Mandab seaway and Nejd Plateau were passable.

“Archaeology without ages is like a jigsaw with the interlocking edges removed — you have lots of individual pieces of information but you can’t fit them together to produce the big picture,” Armitage said.

At Jebel Faya, the ages reveal a fascinating picture in which modern humans migrated out of Africa much earlier than previously thought, helped by global fluctuations in sea-level and climate change in the Arabian peninsula. These findings will stimulate a re-evaluation of the means by which modern humans became a global species.

Author Information

The work at Jebel Faya was directed by Hans-Peter Uerpmann and co-directed by Margarethe Uerpmann of the Centre for Scientific Archaeology at Eberhard-Karls-University Tubingen, and Sabah Jasim, Directorate of Antiquities, Department of Culture and Information, Government of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Palaeolithic artefact analysis was carried out by Anthony Marks and Vitaly Usik. Paleoenvironmental analysis was carried out by Adrian Parker and luminescence dates were calculated by Simon Armitage.

Funding for work at Jebel Faya was provided by the Government of Sharjah, the ROCEEH project (Heidelberg Academy of Sciences), Humboldt Foundation, Oxford Brookes University and the German Science Foundation.

To interview Anthony Marks call SMU News and Communications at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu.

To interview Anthony Marks call SMU News and Communications at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu.