A nomadic tribe pushed into New Mexico by frontier settlement, the Jicarilla slipped off the radar and became the last tribe to avoid forced settlement onto an American Indian reservation

North America’s Jicarilla Apache tribe cloaked themselves in trade, diplomacy, and intermarriage and nearly escaped incarceration on an American Indian reservation. How they did it has been a mystery of the historical American Southwest – until now.

“In some ways, the Jicarilla still remain invisible,” according to anthropologist B. Sunday Eiselt at Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

The Jicarilla Apache, an amalgamation of nomadic tribes that in the 18th century migrated off the plains and settled in the northern Rio Grande of New Mexico, were accustomed to armed resistance, guerrilla tactics and inter-tribal warfare.

They fought alongside the Pueblo Indians in the Revolt of 1680 and later resisted Comanche raiders, sometimes as contract fighters and security guards for the Spanish and American trade caravans. Then quietly, deliberately and peacefully they slipped off the radar of Spanish colonization and U.S. Manifest Destiny until 1888, when the Jicarilla became the last Native American tribe forcibly settled on a reservation.

Invisibility was no accident, rather a strategy for survival

“This was not an accident of history,” says Eiselt. The Apache, particularly the Jicarilla, were experts at invisibility — not just physically, but also socially and economically. For example, Jicarilla warriors on raids would paint themselves during the journey to the plains with white clay to avoid detection by their enemies.

The protocol beckoned supernatural or spiritual protections to bring the warriors home safely. Just as white clay was a warrior strategy for self-preservation, it stands as a metaphor for the primary message of the book.

“By ‘becoming white clay’ in their social and economic dealings,” Eiselt contends, “the Jicarilla turned the tables on non-Indian expansion and disappeared into the cultural fabric of the Southwest’s Pueblo colonies as other Native Americans were being forced onto reservations.” The Jicarilla, without firing a shot, not only avoided confinement and even extermination for nearly two centuries, they rescued their culture from extinction.

How did they manage it?

“The Jicarilla essentially colonized the colonies,” says Eiselt, an expert on the Jicarilla. “They became invisible to government authorities because they were always on the move, they intermarried with the Pueblo and Hispanic peoples, and they established long-standing trade with them. They disappeared by becoming essential, an everyday part of the frontier society of New Mexico, which sustained Spanish, Mexican and ultimately U.S. interests.”

Encapsulation of one society within a larger, dominant or more powerful society is a phenomenon known as enclavement. As a strategy it was not new to the ancestors of the Jicarilla. In fact, enclavement may have occurred multiple times as their Athapaskan ancestors migrated from Canada to the American Southwest beginning as early as the 12th century, Eiselt says.

That phenomenon, however, makes the Jicarilla difficult for scholars to study. Unlike Pueblo archaeology and history, the Jicarilla for the most part have existed outside the realm of historical scholarship in spite of their importance to the social fabric and the economy of New Mexican villages after the fall of the Spanish empire.

Today, bases of tipi rings such as the ones Eiselt identified during field work in the Rio del Oso Valley of New Mexico, are all that remain of historic Jicarilla homes in the archaeological record. Tipi ring stones would have been used to secure the superstructure.

Jicarilla contribution to New Mexico’s history is underappreciated

“Few scholars recognize how significant the Jicarilla contribution was to the survival of the traditional cultures of New Mexico,” says Eiselt, whose new book “Becoming White Clay” (U. of Utah Press, 2012) is a comprehensive study of one of the longest-lived and most successful nomadic ethnic group enclaves in North America. “There hasn’t been a whole lot of research into the Jicarilla, even though they’ve always been there and their contribution to New Mexican history is almost entirely underappreciated.”

Eiselt’s research drew on archaeological investigations, Native American land claims cases, U.S. government agency records, Spanish and Mexican records, oral histories and the tribe’s myths and legends. “Ironically, being invisible is not just how the Jicarilla are, but often how they are ‘seen’ or even missed by scholars of the Southwest,” Eiselt says. The tribe resides today on reservation land in northwestern New Mexico.

A definitive work on Apache history

“Sunday Eiselt has produced the definitive work on Jicarilla Apache history and archaeology,” says Ronald H. Towner, University of Arizona. “She uses a strong theoretical approach to enclavement and combines history, archaeology and ethnohistory to not only describe past Jicarilla movements and cultural development throughout the Southwest, but to explain how and why Jicarilla social organization at different scales structured that development during times of warfare, removal from traditional lands and economic stress. Eiselt’s scholarship is second-to-none.”

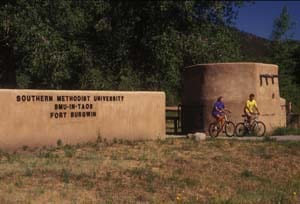

B. Sunday Eiselt is an assistant professor of anthropology at Southern Methodist University and is active in anthropological fieldwork at the SMU Taos campus. She is author or co-author of books and articles on the Jicarilla and Hispanic societies of New Mexico, community-based and engaged approaches in archaeology and ceramic source geochemistry.

“The scholarship is broad, intrinsically sound, and highly significant to the discipline of archaeology today,” says John W. Ives, Institute of Prairie Archaeology and professor of Northern Plains archaeology, University of Alberta. “The author has a fluid, lucid style, making her subject matter readily approachable to both the professional and the interested lay reader.”

Follow SMUResearch.com on Twitter.

For more information, www.smuresearch.com.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Academic achievement improved among students active in structured after-school programs

Academic achievement improved among students active in structured after-school programs Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual

Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance

Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance Middle school boys who are reluctant readers value reading more after using e-readers

Middle school boys who are reluctant readers value reading more after using e-readers

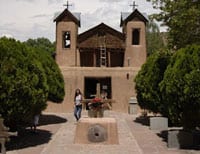

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of  Now Eiselt is launching the SMU-in-Taos

Now Eiselt is launching the SMU-in-Taos  The Ranchos de Taos artifacts bear witness to changes the community has undergone over the past 200 years, she says. Settled by the Spanish in 1716, Ranchos de Taos ultimately absorbed many aspects of Anglo culture. The Catholic grade schools eventually closed, and Hispanic children were forced into the public school system.

The Ranchos de Taos artifacts bear witness to changes the community has undergone over the past 200 years, she says. Settled by the Spanish in 1716, Ranchos de Taos ultimately absorbed many aspects of Anglo culture. The Catholic grade schools eventually closed, and Hispanic children were forced into the public school system. While excavation and research progresses, service projects in the local community also will continue as they have the past few years. University students at the field school work closely with property owners. Each summer 30 undergraduates engage in three weeks of hard labor to re-plaster the historic

While excavation and research progresses, service projects in the local community also will continue as they have the past few years. University students at the field school work closely with property owners. Each summer 30 undergraduates engage in three weeks of hard labor to re-plaster the historic  The goal of the Taos Collaborative Archaeology Program (TCAP) is to unite the strengths of SMU’s community-based archaeology and Mercyhurst’s excavation, documentation and analytical protocols to offer students an unparalleled archaeological training experience.

The goal of the Taos Collaborative Archaeology Program (TCAP) is to unite the strengths of SMU’s community-based archaeology and Mercyhurst’s excavation, documentation and analytical protocols to offer students an unparalleled archaeological training experience. The first TCAP session was June 1 through July 15, and joined 12 students from SMU with 16 from Mercyhurst. SMU’s TCAP director is

The first TCAP session was June 1 through July 15, and joined 12 students from SMU with 16 from Mercyhurst. SMU’s TCAP director is  The Mercyhurst group is supplying a new remote sensing device known as a gladiometer that works in tandem with computer software to detect features and structures buried at shallow depths, to generate subsurface maps and to better target excavation efforts.

The Mercyhurst group is supplying a new remote sensing device known as a gladiometer that works in tandem with computer software to detect features and structures buried at shallow depths, to generate subsurface maps and to better target excavation efforts. SMU-in-Taos has offered summer education programs tailored to the region’s unique resources since 1973, but the rustic campus dormitories were impractical for use during colder weather. New construction, recent renovations to housing and technological improvements provided through a $4 million lead gift from former Texas Gov. William P. Clements and his wife, Rita, will allow SMU students to take a full semester of classes for the first time this fall.

SMU-in-Taos has offered summer education programs tailored to the region’s unique resources since 1973, but the rustic campus dormitories were impractical for use during colder weather. New construction, recent renovations to housing and technological improvements provided through a $4 million lead gift from former Texas Gov. William P. Clements and his wife, Rita, will allow SMU students to take a full semester of classes for the first time this fall.