Led by SMU psychologist and UTSW psychiatrist, Dallas Asthma Brain and Cognition Study will use brain scans to explore relationship between inflammatory lung disease and brain function in older adults

DALLAS (SMU) – SMU psychologist Thomas Ritz and UT Southwestern Medical Center psychiatrist Sherwood Brown will lead a $2.6 million study funded over four years by the National Institutes of Health to explore the apparent connection between asthma and diminished cognitive function in middle-to-late-age adults.

DALLAS (SMU) – SMU psychologist Thomas Ritz and UT Southwestern Medical Center psychiatrist Sherwood Brown will lead a $2.6 million study funded over four years by the National Institutes of Health to explore the apparent connection between asthma and diminished cognitive function in middle-to-late-age adults.

The World Health Organization estimates that 235 million people suffer from asthma worldwide.

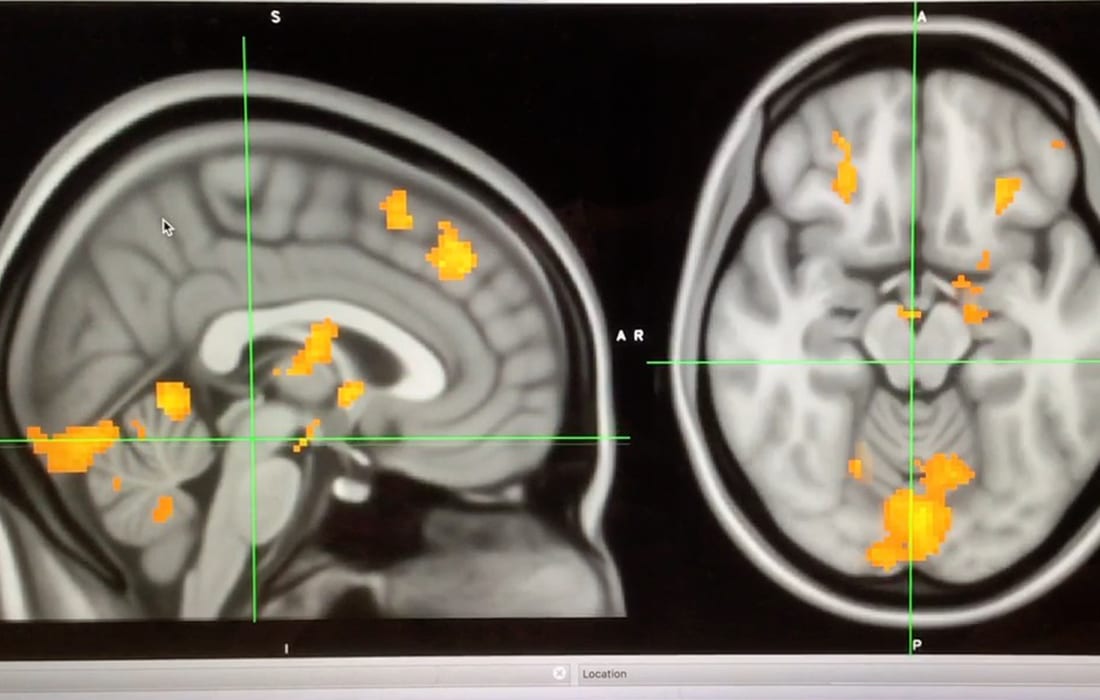

The study will build on the work Brown and Ritz have accomplished with a core group of researchers over a period of eight years. Their pilot data, gleaned from brain imaging and analysis of chemical changes, indicates that neurons in the hippocampus of young-to-middle-age adults with asthma are not as healthy as those in the control group without asthma. The hippocampus is that portion of the brain that controls long-term memory and spatial navigation.

“In our early study, we found that there were differences between healthy control participants and young-to-middle-age asthma patients in that the latter showed a slightly lower performance in cognitive tasks,” Ritz said. “We wonder how that looks in older age. When you have asthma for a lifetime, the burden of the disease may accumulate.”

The early findings also led his group to wonder if the impact on cognition is related to the severity of the disease.

“This all makes sense, but no one has looked specifically at how that relates to brain structure,” Ritz said. “With this grant we will look at structures – the neurons and axons, the white and gray matter of the brain, how thick they are in various places. We look at what kind of chemicals have been accumulating, which are the byproducts of neural activity. We want to know how various areas of the brain function during cognitive tasks.”

The four-year project will allow researchers to study a sample of up to 200 participants who are between the ages of 40-69. In addition to Ritz and Brown, the research group includes Denise C. Park, director of research for the Center for Vital Longevity at the University of Texas at Dallas; Changho Choi, professor of radiology at UTSW; David Khan, professor of internal medicine at UTSW; Alicia E. Meuret, professor of clinical psychology at SMU, and David Rosenfield, associate professor of psychology at SMU. SMU graduate students working on the grant are Juliet Kroll and Hannah Nordberg.

“This is how neuroimaging works today – it is a team sport,” Ritz said. “You cannot do it on your own. You have to strike up collaborations with various disciplines. It’s very exciting because it is stimulating and interesting to collaborate with colleagues in different areas.”

The study, scheduled to run through May 31, 2022, will allow the research team to examine several possible factors that may impact cognition in people with asthma.

“Is it lack of oxygen? That’s a very good question,” Ritz said. “But it cannot be the full story. Real lack of oxygen only happens in severe asthma attacks and in most cases, people having an asthma attack are still well saturated with oxygen.

Carbon dioxide levels are often too low in asthma patients – but it is uncertain whether that is a .”

Another possibility, he said, is that the problems with disrupted sleep experienced by many people with asthma might relate to cognitive function.

“Just imagine you how you perform after lack of sleep,” Ritz said. “In the long run, we know sleep is important to the health of our brain. If over a lifetime you’ve had interruptions in sleep, it may impact your neural health.”

This research is being supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number 1R01HL142775-01.