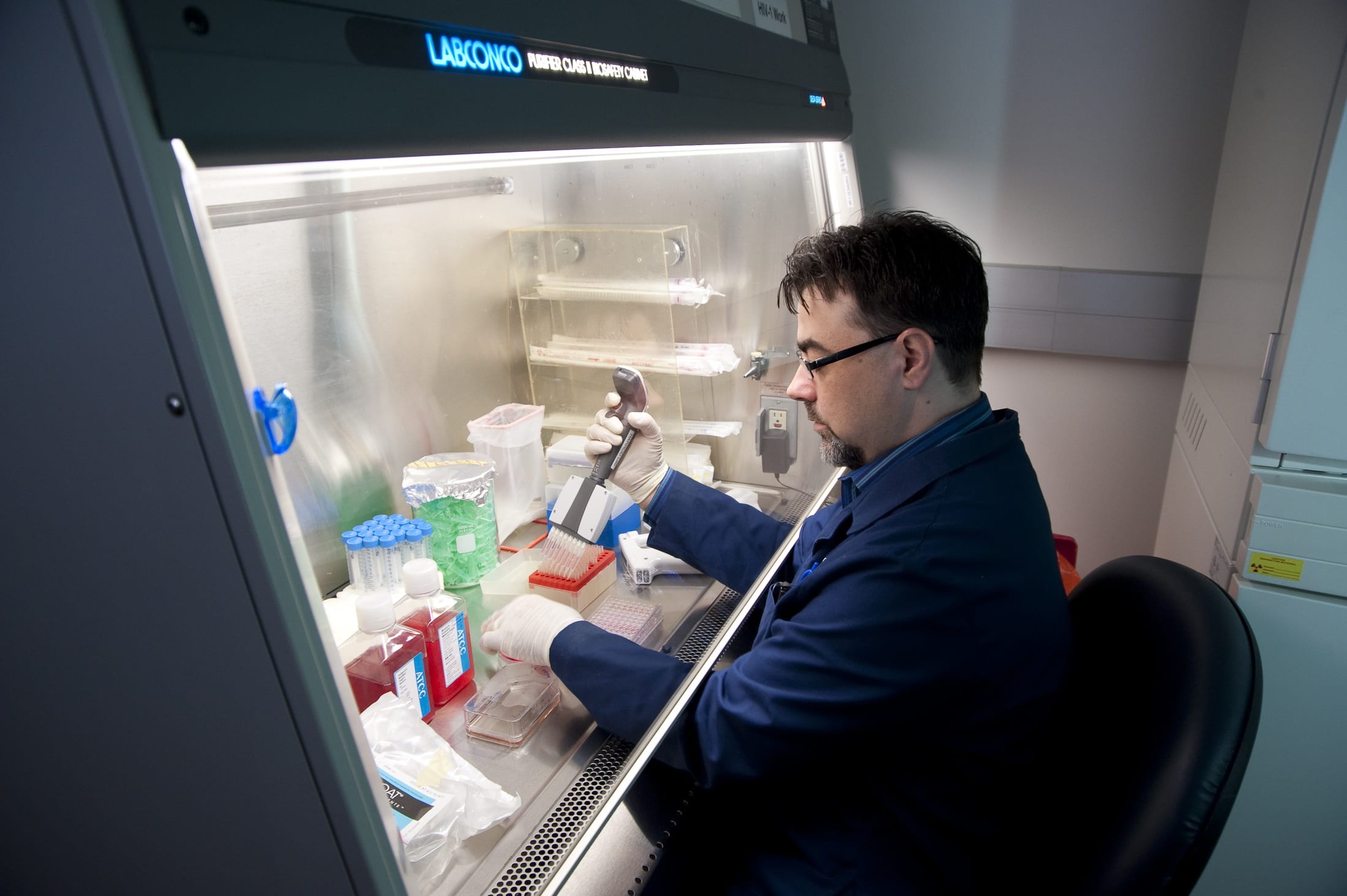

In his third-floor laboratory in Dedman Life Sciences Building, biologist Robert Harrod and his team are zeroing in on a new way to inhibit the virus that causes AIDS. They already have shown that their approach, which involves the rare genetic disorder Werner syndrome, works when the disorder’s enzyme defect is introduced into cells.

Now they are trying to find practical ways to use this pathway to inhibit the AIDS virus. The beauty of this approach is that the AIDS virus will not be able to mutate in a way that can defeat this treatment, says Harrod, associate professor in the Biological Sciences Department of Dedman College.

Down the hall from Harrod’s lab, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences Jim Waddle is preparing to file for a patent on a tiny “worm” that is expected to be highly useful in drug-testing, producing results far more quickly than tests run on larger lab creatures.

Meanwhile, their colleagues, Associate Professor Pia Vogel and her husband, John Wise, a lecturer in the Biological Sciences Department, are conducting work that may have implications for cancer treatment.

In university laboratories throughout the world, enormous strides have been made in biology research in recent years, including the mapping of the human genome. With young faculty members like Harrod, Waddle and Vogel working on cutting-edge conundrums, and a recent $3.6 million gift to Biological Sciences, SMU’s department is poised to play a high-profile role in biology advances in coming years, says William Orr, chair and professor of biological sciences.

The gift from philanthropist and SMU Board of Trustees member Caren Prothro and the Perkins-Prothro Foundation includes $2 million for an endowed chair, $1 million for an endowed research fund, $500,000 for a graduate fellowship fund and $100,000 for an undergraduate scholarship fund.

The endowment will enable the University to attract a biologist with a national reputation in research to join a faculty that is strong in cellular and molecular biology and biochemistry and is doing research that could have practical applications in medicine, Orr says.

For example, Vogel and Wise are looking for a way to improve the long-term efficacy of chemotherapy treatments. Wise uses a nautical metaphor to explain their work: “Picture a cancer cell as a ship on a sea and the chemotherapy being dumped into the ship, there’s a mechanism like a sump pump that will dump that chemical back overboard,” he says.

That cellular “sump pump” is important to normal cell health because it keeps toxins out.

“Of course, with cancer cells that are targeted for destruction by chemotherapeutics, you’d like to be able to turn off that mechanism,” Wise adds.

John Wise

Vogel explains that many cancer cells respond to treatment by pumping out more and more of the toxins as time goes on, so that a cancer treatment that works well initially might not work as well in later stages.

“Switching chemotherapy drugs doesn’t help because the cancer cells just pump out everything, resulting in multi-drug resistance,” she says.

Using Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy, a biophysical technique that obtains structural information about the cellular pump, Vogel’s research group is trying to find a way to shut off the ATP energy usage by this cellular sump pump.

“If you can knock out the pump, you can sink the cancer ship,” she says.

Harrod, who studies retroviruses that infect humans and who is focusing on transcriptional gene regulation, is working on a mechanism that might sidestep a more specific type of multidrug resistance — of the virus that causes AIDS to the conventional HAART (highly active antiretroviral treatment) drug regimen.

Pia Vogel

His approach is related to a rare genetic disorder called Werner syndrome, which causes premature aging in those who have the disease. Researchers have noted that individuals who are carriers for Werner syndrome do not develop AIDS. Harrod hypothesized that the enzyme involved in Werner syndrome is necessary for transcription of the retrovirus.

Using cells that had the Werner syndrome defect inserted into them, his lab was able to confirm this link, and last year he and co-researchers published the findings in “The Journal of Biological Chemistry.” Now his group is looking for molecules that might be used to block this transcription-necessary enzyme. Included among the researchers cited in the journal article were several biological sciences students. Both graduate and undergraduate students assisted Harrod in his lab work on retroviral transcription.

Ask Assistant Professor Jim Waddle about the contributions made by students, and he’ll talk about the weird “worm” discovered by one of his graduate students. Waddle, whose Ph.D. work was in molecular genetics, has been studying the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for food absorption in the human gut.

Fingerlike projections called microvilli, which are necessary for the absorption of nutrients, line the human gut; nematodes have microvilli on every gut cell.

As part of their research, Waddle’s lab doused the nematodes in mutation-causing chemicals and examined them via a fluorescent protein.

Ph.D. candidate Christina Paulson looked at 20,000 nematodes in this manner and came up with one that had a nematode version of diverticulosis, with outpouchings all along the gut.

Disappointingly, the mutated worm turned out to be normal in terms of lifespan, reproduction and absorption of nutrients. But, Waddle says, “we threw our heads together and thought about conditions the nematode might encounter in the wild” versus the laboratory setting. He wondered if the worm might have trouble eliminating toxins. It did.

Jim Waddle

Normal nematodes eliminate toxins too quickly for the worms to be useful in drug testing, but toxins stay in the weird worms long enough to have an effect on them. And that means the millimeter-long creature likely will be highly useful in drug-testing situations, because a nematode’s life cycle is so much shorter than that of the larger animals, such as mice, that generally are used to test drugs.

The student who identified the worm is one of 18 graduate students in the Department of Biological Sciences. Nine are working on Master’s degrees, nine on Ph.Ds. With 126 undergraduates, the department enrolls the largest segment of undergraduate majors in the natural sciences at SMU. Undergraduate students who intend to go into biological research can apply for the BRITE (Biomedical Researchers in Training Experience) program, a collaboration between SMU and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center that leads to acceptance into a UT Southwestern Ph.D. program.

Orr believes the department is poised for a leap forward in size and stature. Administrative support to boost research has come from Provost Paul Ludden, whose background is in biochemistry. Current research projects are supported by $4.3 million from agencies that include the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Christina Paulson

Orr’s dream for the department is to double the current tenured and tenure-track faculty to 18 members. Of the nine, seven conduct ongoing research projects, five of which are funded by federal agencies. The department will add an assistant professor in spring 2009. Later that year, a national search will be conducted to fill the new Distinguished Chair of Biological Sciences.

Although the department is small, a synergy has developed from building a faculty that is focused on cellular and molecular biochemistry, Orr says.

Although the department is small, a synergy has developed from building a faculty that is focused on cellular and molecular biochemistry, Orr says.

Researchers can work together on projects, brainstorming ideas for new areas of investigation. More grants can be applied for, which means more grants awarded.

“We have a strong group that is focused on certain areas. By adding new faculty we will be able to boost the overall stature of the department,” Orr says. “If we increase the academic stature and the amount of research, we can provide more opportunities for graduate students and for undergraduates. It all works together.” — Cathy Frisinger

William Orr

Related links:

Robert Harrod

Jim Waddle

Pia Vogel

John Wise

William Orr

Biological Sciences Department

Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences

Help wanted: Principals who embrace change in wake of Race to the Top

Help wanted: Principals who embrace change in wake of Race to the Top Observed by Texas telescope: Light from huge explosion 12 billion years ago reaches Earth

Observed by Texas telescope: Light from huge explosion 12 billion years ago reaches Earth Low IQ students learn to read at 1st-grade level after persistent, intensive instruction

Low IQ students learn to read at 1st-grade level after persistent, intensive instruction Richest marine reptile fossil bed along Africa’s South Atlantic coast is dated at 71.5 mya

Richest marine reptile fossil bed along Africa’s South Atlantic coast is dated at 71.5 mya Satellite view of volcanoes finds the link between ground deformation and eruption

Satellite view of volcanoes finds the link between ground deformation and eruption Comet theory false; doesn’t explain cold snap at the end of the Ice Age, Clovis changes or mass animal extinction

Comet theory false; doesn’t explain cold snap at the end of the Ice Age, Clovis changes or mass animal extinction

It is a discussion that seems familiar. But new findings show that people who travel frequently are more likely to experience déjà vu. Political liberals report more déjà vu experiences than conservatives do. And déjà vu becomes less common as people grow older.

It is a discussion that seems familiar. But new findings show that people who travel frequently are more likely to experience déjà vu. Political liberals report more déjà vu experiences than conservatives do. And déjà vu becomes less common as people grow older.