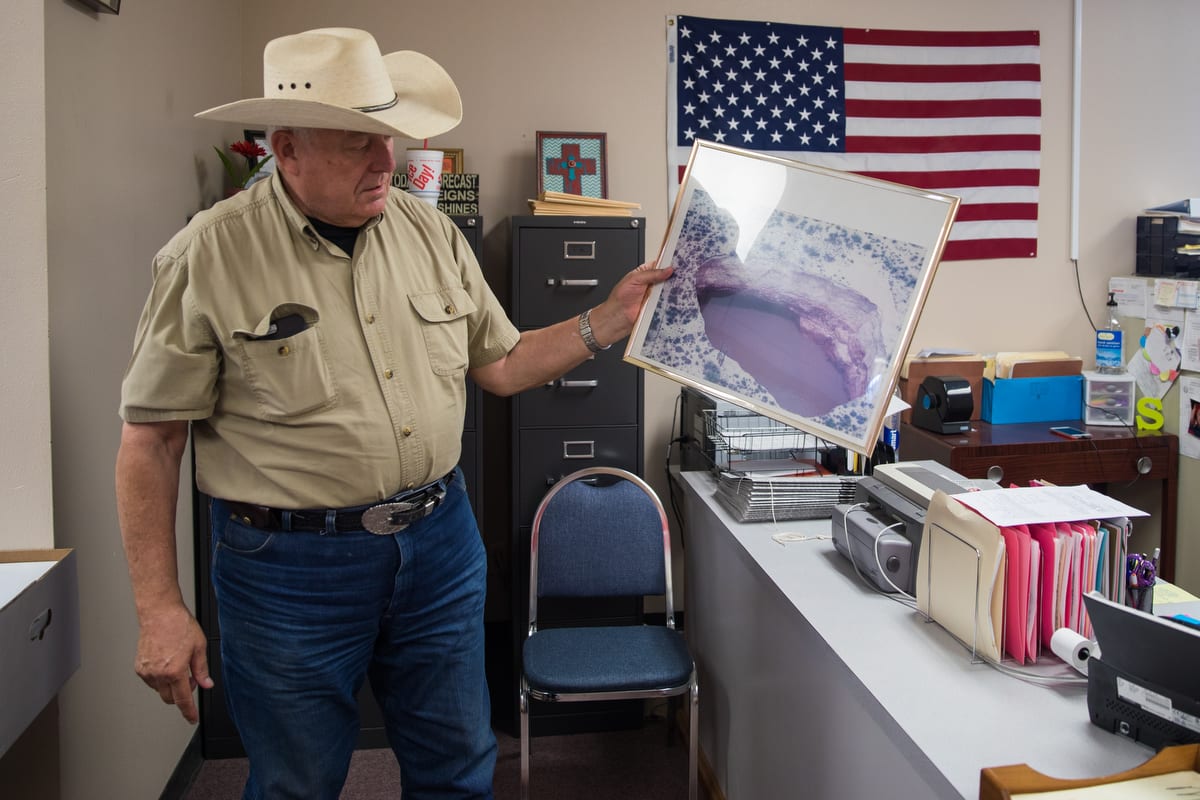

If the hole dramatically expands, “Wink will have some beachfront property,” Keely jokes. “Somebody’s going to make a marina out of it.” — Winkler County Sheriff George Keely to The Texas Tribune.

The Texas Tribune journalist Jim Malewitz covered the research of SMU geophysicists Zhong Lu, professor, Shuler-Foscue Chair, and Jin-Woo Kim research scientist, both in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at SMU. Malewitz’s article, “Sinkhole Warnings Don’t Faze West Texas,” published July 12, 2016.

The Dedman College geophysicists are co-authors of a new analysis using satellite radar images to reveal ground movement of two giant sinkholes near Wink, Texas. They found that the movement suggests the two existing holes are expanding, and new ones are forming as nearby subsidence occurs at an alarming rate.

Lu is world-renowned for leading scientists in InSAR applications, short for a technique called interferometric synthetic aperture radar, to detect surface changes that aren’t visible to the naked eye. Lu is a member of the Science Definition Team for the dedicated U.S. and Indian NASA-ISRO InSAR mission, set for launch in 2020 to study hazards and global environmental change.

InSAR accesses a series of images captured by a read-out radar instrument mounted on the orbiting satellite Sentinel-1A. Sentinel-1A was launched in April 2014 as part of the European Union’s Copernicus program.

Lu and Kim reported the findings in the scientific journal Remote Sensing, in the article “Ongoing deformation of sinkholes in Wink, Texas, observed by time-series Sentinel-1A SAR Interferometry.”

The research was supported by the U.S. Geological Survey Land Remote Sensing Program, the NASA Earth Surface & Interior Program, and the Shuler-Foscue Endowment at Southern Methodist University.

EXCERPT:

By Jim Malewitz

The Texas Tribune

WINK — Sheriff George Keely’s truck bobbed as he cruised down a particularly warped and cracked stretch of county road.“This is the road I don’t like to drive on if I don’t have to,” he said as brown-green West Texas scrubland reflected in the rearview mirror. The trip is riskier than he’d like.

But here was Keely — a few months away from retirement after more than 20 years as a Winkler County lawman, five of them as sheriff — again escorting a reporter and photographer across the unstable terrain toward the Wink Sinks, the community’s chasms of fascination and fear.

The two gaping sinkholes, which sit between the small towns of Wink and Kermit atop the largely tapped out Hendrick oilfield, aren’t new. Wink Sink No. 1 — more than a football field across and 100 feet deep when it collapsed — turned 36 years old last month. Its more massive cousin to the south, Wink Sink No.2, swallowed a water well, pipelines and surrounding desert back in 2002.

A recent study by two Southern Methodist University geophysicists has thrust the sinkholes back into conversations here and across the wider realm of social media.

The research, published last month in the peer-reviewed journal Remote Sensing, used satellite imagery to chart what other researchers and folks like Keely have noticed: the sinkholes keep growing, and land surrounding them is sinking — likely due to a mix of geology and human intervention.

The instability raises the possibility that more abysses could open without further notice, the SMU researchers suggested.

“A collapse could be catastrophic,” research scientist Jin-Woo Kim said in a statement upon the study’s release.

“I would be very concerned,” his partner Zhong Lu, a professor, said in an interview.

Those findings quickly garnered attention from news media across Texas and the U.S. and other websites. The headlines grew more alarming and less accurate as blogs and other websites aggregated and re-aggregated the news. (“Giant Sinkholes Threaten to Swallow Two Tiny West Texas Towns,” “Sinkholes May Take Texas Down”).

In Winkler County, the prognostications were greeted largely with a yawn.

Follow SMU Research on Twitter, @smuresearch.

For more SMU research see www.smuresearch.com.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information, www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

To request an interview with Zhong Lu call SMU News and Communications at 214-768-7650 or email SMU News at

To request an interview with Zhong Lu call SMU News and Communications at 214-768-7650 or email SMU News at  To request an interview with Jin-woo Kim call SMU News and Communications at 214-768-7650 or email SMU News at

To request an interview with Jin-woo Kim call SMU News and Communications at 214-768-7650 or email SMU News at  Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger

Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data

SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns

Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple

Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought

Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought