Reading skill fails to improve when schools follow current practices that require struggling readers to fail first before they merit tutoring or extra teaching

Reading skills improve very little when schools follow the current standard practice of waiting for struggling readers to fail first before providing them with additional help, according to researchers at Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

In contrast, a recent study found that a dynamic intervention in which struggling readers received the most intensive help immediately, enabled students to significantly outperform their peers who had to wait for additional help, said Stephanie Al Otaiba, lead author on the research.

“We studied how well struggling readers respond to generally effective standard protocols of intervention to help them improve. We found that how those interventions are provided within a school — how immediately they are provided — makes an important difference,” said Al Otaiba, professor of teaching and learning in the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development at SMU.

Proficient reading is critical, and early intervention is imperative, said co-author and academic skills measurement expert Paul Yovanoff, also a professor of teaching and learning in the Simmons School.

About 40 percent of U.S. children in fourth grade do not read at a proficient level, Yovanoff said.

“We’re not talking about a small group of children,” he said. “We’re talking about a large group. And the number is higher in urban areas and higher among minority students. How can these kids grow up and participate in society as moms and dads in the economy unless they’re literate? Reading is a bottleneck for their success in school and in life.”

Determined to help more struggling readers, the researchers hope the findings of their study will lead to further research that helps educators identify where the malleable levers are for change within school systems and in professional development for teachers.

“It’s possible schools could manage interventions and assess interventions differently,” Al Otaiba said. “And schools might also provide teachers with different or added professional development, coaching and support, particularly where so many struggling readers are included in general education for a large portion of the school day.”

A wait-to-fail system can be the unintended consequence of response to intervention as it’s currently practiced in U.S. schools, the researchers said.

“If you have to wait a certain time to demonstrate that you need more help, then it’s a wait-to-fail system,” Yovanoff said. “Good teaching would collect frequent information about the student’s performance and adjust help appropriately.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health.

Co-author was Jeanne Wanzek, the Florida Center for Reading Research, Florida State University.

The researchers reported the findings in their article “Response to Intervention” in the European Scientific Journal. It’s published online at the European Scientific Journal site.

Those with intensive intervention immediately outperformed

The study, initiated in 2011, followed 522 first grade public school students for three years through third grade.

At the start of the study, the children were young beginning readers with the poorest initial reading skills, who were struggling and at risk for developing reading disabilities.

The children were randomly sorted into two groups. One group was assigned to receive an immediate and intensive intervention, which included additional structured reading instruction 45 minutes a day, four days a week, in subgroups of three to five students.

The second group started with good classroom instruction. Children who didn’t respond well after eight weeks received additional help. If they continued not to respond, they received another layer of help. Educators call this approach a multi-tier model of response to intervention.

“We contrasted the multi-tier model with what we call a dynamic model, where we gave kids with the weakest initial skills the strongest intervention right away,” Al Otaiba said. “The kids in the dynamic system outperformed the kids who got help later.”

Struggling readers boosted skills significantly

The researchers followed up on the students in third grade, and found that those that had received the immediate intensive intervention continued to outperform the children who had to wait, Al Otaiba said.

Those children are now in sixth grade, and the researchers continue to monitor their performance.

Students in the study who received appropriate intensive interventions significantly outperformed the students who had to wait by a third of a standard deviation, Yovanoff said

“So when we say our intervention has improved performance by a third of a standard deviation, we’ve increased their skill beyond a random fluctuation in performance,” he said “We’re quite confident this child has in fact learned to a very significant degree. It’s statistically significant.”

Even those helped the most failed to catch up with peers

Did struggling readers who improved catch up to their non-struggling peers, however?

Yes — in their ability to pronounce and read a real word, the researchers found.

But they continued to lag behind their peers in how fast they could read, and in intonation and comprehension.

“Still, they were less far behind in those areas than the kids who had to wait to get help,” Al Otaiba said.

The researchers measured growth and change over time, as opposed to a student’s performance at one specific point. So as time goes on, it’s possible to see the gap closing, the researchers said.

The researchers hope the study findings will guide schools in effective intervention practices.

“The notion is to develop more intensive, individualized interventions to help prevent reading problems and maximize reading skills for children who are struggling,” Al Otaiba said. — Margaret Allen

Follow SMUResearch.com on twitter at @smuresearch.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Top Quark: New precise particle measurement improves subatomic tool for probing mysteries of universe

Top Quark: New precise particle measurement improves subatomic tool for probing mysteries of universe New fossils intensify mystery of short-lived, toothy mammals unique to ancient North Pacific

New fossils intensify mystery of short-lived, toothy mammals unique to ancient North Pacific Drugs behave as predicted in computer model of key protein, enabling cancer drug discovery

Drugs behave as predicted in computer model of key protein, enabling cancer drug discovery Researchers discover new drug-like compounds that may improve odds for men battling prostate cancer

Researchers discover new drug-like compounds that may improve odds for men battling prostate cancer Fermilab experiment observes change in neutrinos from one type to another over 500 miles

Fermilab experiment observes change in neutrinos from one type to another over 500 miles Large genome-scale study finds Native American ancestors arrived in single migration wave

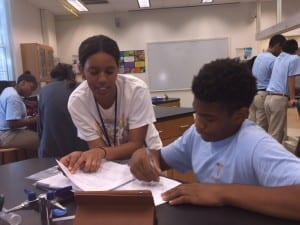

Large genome-scale study finds Native American ancestors arrived in single migration wave $3.78 million awarded by Department of Defense to SMU STEM project for minority students

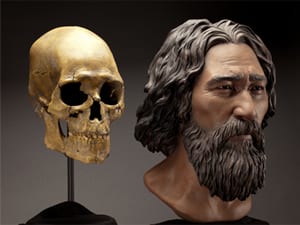

$3.78 million awarded by Department of Defense to SMU STEM project for minority students Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy

Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy At peak fertility, women who desire to maintain body attractiveness report they eat less

At peak fertility, women who desire to maintain body attractiveness report they eat less SMU seismology team to cooperate with state, federal scientists in study of May 7 Venus, Texas earthquake

SMU seismology team to cooperate with state, federal scientists in study of May 7 Venus, Texas earthquake 1st proton collisions at the world’s largest science experiment expected to start the first or second week of June

1st proton collisions at the world’s largest science experiment expected to start the first or second week of June