Through their research, SMU professors not only bring new information and insights to their classrooms, but also serve as role models and collaborators to students who conduct research in their laboratories across campus.

Maintaining a strong research program is significant for a number of reasons, says James Quick, associate vice president for research and dean of graduate studies.

“Research programs serve as a recruiting tool that helps a university attract the best students,” Quick says. “Research also increases the diversity of ideas on campus and creates opportunities for different departments to work together on interdisciplinary projects.”

In support of SMU’s commitment to research at both faculty and student levels, which is part of the University’s long-term strategic plan, Quick is seeking to more than triple SMU’s annual research spending to $50 million.

He emphasizes that the top 50 universities in the country, as ranked by “U.S. News & World Report,” each conduct more than $50 million a year in research.

“The great universities of the 21st century will spend significant amounts of funds on research,” Quick says. From anthropology to engineering to religious studies, SMU undergraduate and graduate students and their faculty mentors are discovering new knowledge and playing an important role in higher education through their contributions to research.

Lessons From Bolivia

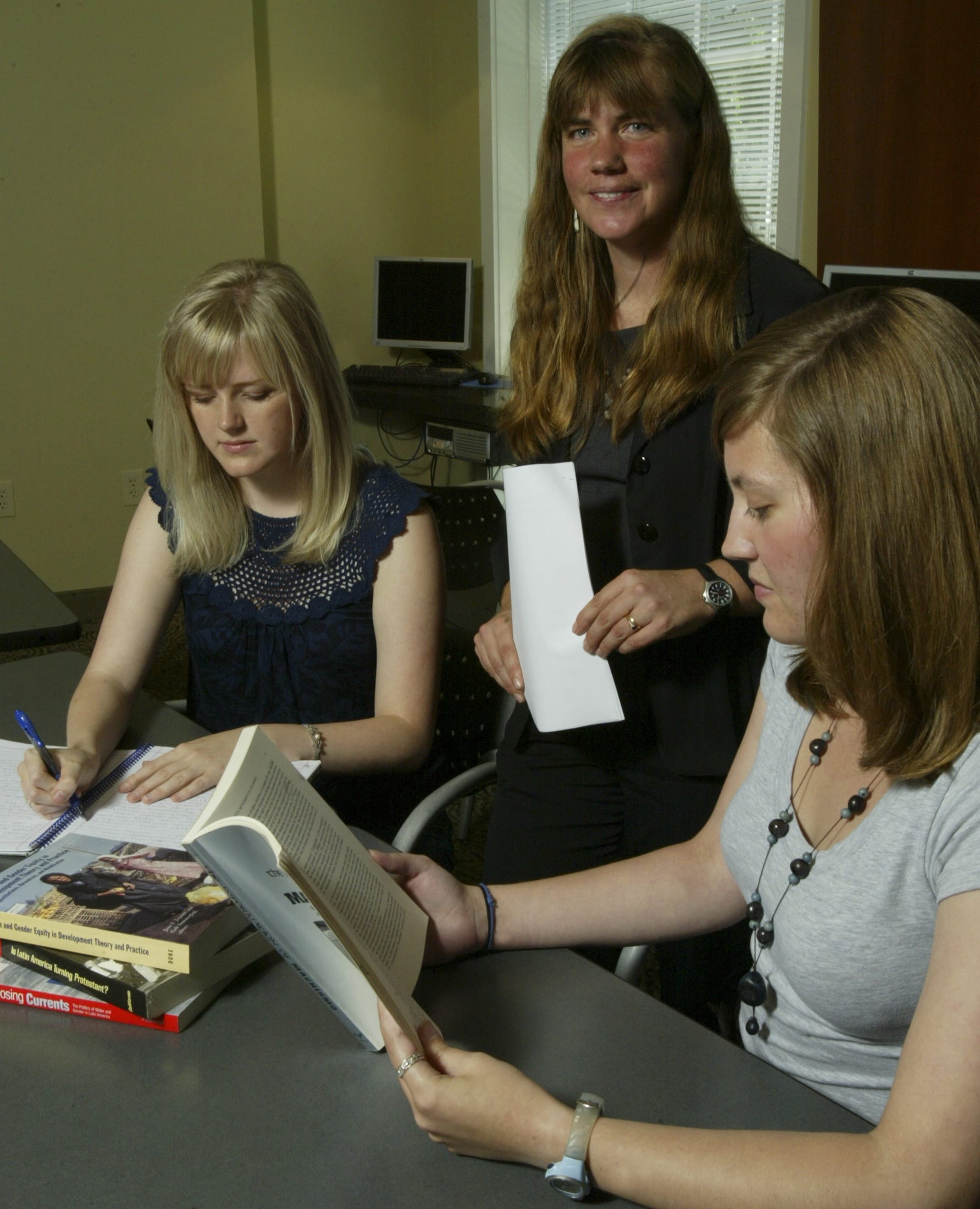

In summer 2007, SMU Seniors Erin Eidenshink and Katie Josephson spent eight weeks in Cochabamba, Bolivia’s third-largest city, researching gender roles and how they affect economic development programs in that country. Eidenshink and Josephson received financial support from the Richter International Fellowship Program, which funds independent research abroad for students in SMU’s Honors Program.

Jill DeTemple, assistant professor of religious studies in Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences, served as their adviser on the research. DeTemple, whose own research examines the effects of faith-based development programs on religious identity in rural Ecuador, spent a semester helping the two students develop a research proposal. She later remained in contact with them by e-mail while they were in Bolivia.

“I am immensely proud of what they accomplished,” DeTemple says. “They applied knowledge that they learned in the classroom and developed research skills. They have made the transition from being consumers of knowledge to being creators of knowledge.”

Now a book chapter written by the students and DeTemple, describing the messages that faith-based organizations communicate about gender roles, has been accepted into an anthology under review for publication.

“Their work highlights the ways in which most development organizations and scholars presume that men and women relate to households and family life,” DeTemple says.

“While we have noted that the evangelical movement in Latin America has brought men in closer relationship to household life, Katie and Erin point out that this has not necessarily freed women to become more active in the public sector, nor has it led to gender parity in the household,” she says. “I learned a lot from their research, and will look at gender roles a little bit differently when I do my research.”

DeTemple says she also has enjoyed interesting conversations with Eidenshink and Josephson.

“Because no one else on campus is doing research in my area, I don’t have these kinds of conversations unless I go to a professional conference,” DeTemple says. “They’re working in the field now. We talk as researcher to researcher.”

Eidenshink says that working with DeTemple and conducting the research “empowered me to draw my own conclusions.”

In addition, DeTemple “challenged us to look at the research that already had been done and then to analyze it based on what we had seen,” says Josephson, a President’s Scholar. “We found that the facts were complex, not simple and straightforward,” she says.

In addition, DeTemple “challenged us to look at the research that already had been done and then to analyze it based on what we had seen,” says Josephson, a President’s Scholar. “We found that the facts were complex, not simple and straightforward,” she says.

From cheerleader to colleague

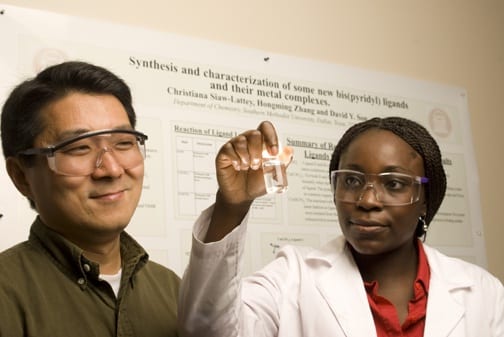

Christiana Rissing, a Ph.D. student in SMU’s Chemistry Department, studies the interaction of dendrimers based on a tetravinylsilane core with metals like copper, platinum and silver. Any interesting properties that develop “could prove useful for medical and electronic applications,” she explains.

If she has any questions, Rissing can call on Associate Professor of Chemistry David Son, her adviser. She began studying with Son as an undergraduate and stayed at SMU to pursue her Ph.D. because she enjoys working with him.

David Son advises Christiana Rissing.

“In the lab, we’re always teasing Son about his favorite line: ‘It looks promising,'” Rissing says. “He always looks for and finds the silver lining. I can work on a stubborn experiment for weeks, and I start questioning my technique. Even when the results look bad, he will look at all the data and find something that ‘looks promising.’ It makes me want to go that extra step, read that extra paper or search through the literature in case I’ve missed something.”

As a Ph.D. student, Rissing works independently, Son says.

“I treat her more like a colleague now. But, in the beginning, with any student, you have to be a cheerleader,” he says. “When I was a graduate student, more than half of my reactions didn’t work. A big part of my role is to be an encourager.”

The research opportunity

Junior Amy Hand is writing a computer program to design a solenoid magnet that students will use in the physics lab to study the properties of “muons,” electron-like radioactive particles produced in Earth’s upper atmosphere. A solenoid magnet is made by wrapping copper wire in a pattern around a specially shaped mechanical frame to produce a uniform magnetic field within the frame’s interior.

Hand, a President’s Scholar, chose to study at SMU because of research opportunities made available to undergraduates, she says.

“Working with a professor who has so much more experience and can guide me through a project is a huge benefit,” Hand says.

Amy Hand learns the ropes in the physics lab

from Tom Coan.

Tom Coan, associate professor of physics and Hand’s adviser, helps students to develop a broad set of skills, from learning how to solder to selecting and purchasing mechanical and electrical components.

“There are a lot of practical things and a bewildering assortment of things that students have to learn to be efficient in a lab,” Coan says.

Hand researches, tests and refines the various components of her project, working closely with Coan to devise solutions as issues arise.

“The best way to learn the nitty-gritty details is elbow to elbow with a mentor,” Coan says. “It’s like an apprenticeship. You have to invest a fair amount of your time working with a student before you see any return, but the work can be beneficial to both of us.”

Planting The Seed Of Research

Sophomore Jason Stegall spent last summer in the Laser Micromachining Laboratory of the Bobby B. Lyle School of Engineering using a laser process called micromachining to cut tiny channels on material that can be used to make artificial bones.

Sophomore Jason Stegall spent last summer in the Laser Micromachining Laboratory of the Bobby B. Lyle School of Engineering using a laser process called micromachining to cut tiny channels on material that can be used to make artificial bones.

“I was testing to see how strong the laser needed to be and how many pulses were required per task,” Stegall says.

Jason Stegall (center) in the lab with David

Willis (left) and Paul Krueger.

A National Science Foundation grant awarded to David Willis and Paul Krueger, associate professors of mechanical engineering, supported Stegall’s research. The three-year grant funds summer research opportunities for nine undergraduate students through 2009.

Through such grants the federal government is trying to encourage more students to conduct research and go to graduate school in engineering and the sciences, Willis says.

“Part of the reason more students don’t go to graduate school is that they don’t know what researchers do, and don’t understand all the opportunities that are available to researchers,” he says.

Stegall says he eventually wants to become a college professor and do research and development for the automotive or aerospace industries.

Torrey Rick’s research involves excavating sites as old as 10,000 years on the Channel Islands off the California coast.

“The work I do is extremely collaborative,” says Rick, assistant professor of anthropology. “Students are an important part of this work, helping to complete field and laboratory analysis and often providing fresh ideas and perspectives. Conducting research also benefits students by showing them how to navigate the world of scholarly publication. Ultimately, doing research and publishing papers can help them secure an academic position.” – Joy Hart

Torrey Rick (center) and Ph.D. students Amanda Aland

and Christopher Wolff.

Related links:

Jill DeTemple

David Son

Tom Coan

David Willis

Paul Krueger

Torrey Rick

Office of Research Administration

SMU Research: Celebrating and Investing in Research at SMU

Krueger believes that pulsed jets, consisting of a series of jet pulses with no flow between them, is a promising approach to developing micropropulsion capability. He plans to develop a model system that propels itself using pulsed jets generated by a volume-displacement mechanism. The behavior of this representative vehicle will help reveal how to adapt pulsed jet propulsion for small-scale vehicles.

Krueger believes that pulsed jets, consisting of a series of jet pulses with no flow between them, is a promising approach to developing micropropulsion capability. He plans to develop a model system that propels itself using pulsed jets generated by a volume-displacement mechanism. The behavior of this representative vehicle will help reveal how to adapt pulsed jet propulsion for small-scale vehicles.