Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Peter Weyand in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Related links

- Peter Weyand

- Journal of Applied Physiology: “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up”

- Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development

More SMU Research news

Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt‘s record-setting performances have unleashed a wave of interest in the ultimate limits to human running speed. A new study published Jan. 21 in the Journal of Applied Physiology offers intriguing insights into the biology and perhaps even the future of human running speed.

The newly published evidence identifies the critical variable imposing the biological limit to running speed, and offers an enticing view of how the biological limits might be pushed back beyond the nearly 28 miles per hour speeds achieved by Bolt to speeds of perhaps 35 or even 40 miles per hour.

The new paper, “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up,” was authored by Peter Weyand of Southern Methodist University; Rosalind Sandell and Danille Prime, both formerly of Rice University; and Matthew Bundle of the University of Wyoming.

“The prevailing view that speed is limited by the force with which the limbs can strike the running surface is an eminently reasonable one,” said Weyand, associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics at SMU in Dallas.

“If one considers that elite sprinters can apply peak forces of 800 to 1,000 pounds with a single limb during each sprinting step, it’s easy to believe that runners are probably operating at or near the force limits of their muscles and limbs,” he said. “However, our new data clearly show that this is not the case. Despite how large the running forces can be, we found that the limbs are capable of applying much greater ground forces than those present during top-speed forward running.”

|

| SMU sprinter Ebony Cuington. Photo: SMU Athletics |

In contrast to a force limit, what the researchers found was that the critical biological limit is imposed by time — specifically, the very brief periods of time available to apply force to the ground while sprinting.

In elite sprinters, foot-ground contact times are less than one-tenth of one second, and peak ground forces occur within less than one-twentieth of one second of the first instant of foot-ground contact.

The researchers took advantage of several experimental tools to arrive at the new conclusions. They used a high-speed treadmill capable of attaining speeds greater than 40 miles per hour and of acquiring precise measurements of the forces applied to the surface with each footfall. They also had subjects’ perform at high speeds in different gaits. In addition to completing traditional top-speed forward running tests, subjects hopped on one leg and ran backward to their fastest possible speeds on the treadmill.

The unconventional tests were strategically selected to test the prevailing beliefs about mechanical factors that limit human running speeds — specifically, the idea that the speed limit is imposed by how forcefully a runner’s limbs can strike the ground.

However, the researchers found that the ground forces applied while hopping on one leg at top speed exceeded those applied during top-speed forward running by 30 percent or more, and that the forces generated by the active muscles within the limb were roughly 1.5 to 2 times greater in the one-legged hopping gait.

The time limit conclusion was supported by the agreement of the minimum foot-ground contact times observed during top-speed backward and forward running. Although top backward vs. forward speeds were substantially slower, as expected, the minimum periods of foot-ground contact at top backward and forward speeds were essentially identical.

According to Matthew Bundle, an assistant professor of biomechanics at the University of Wyoming, “The very close agreement in the briefest periods of foot-ground contact at top speed in these two very different gaits points to a biological limit on how quickly the active muscle fibers can generate the forces necessary to get the runner back up off the ground during each step.”

The researchers said the new work shows that running speed limits are set by the contractile speed limits of the muscle fibers themselves, with fiber contractile speeds setting the limit on how quickly the runner’s limb can apply force to the running surface.

The established relationship between ground forces and speed allowed the researchers to calculate how much additional speed the hopping forces would provide if they were utilized during running.

“Our simple projections indicate that muscle contractile speeds that would allow for maximal or near-maximal forces would permit running speeds of 35 to 40 miles per hour and conceivably faster,” Bundle said.

New Mexico “Childhood Archaeology Project” unearths centuries of change

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date September 15, 2009

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of Ranchos de Taos in northern New Mexico.

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of Ranchos de Taos in northern New Mexico.

The plaza, once a hub of village life in Ranchos de Taos, these days is notably absent of children. Their families have been driven to the outskirts of the Catholic village by a booming tourism industry that has pushed up property values.

But the children left their mark, says archaeologist Sunday Eiselt, who for three years has led digging crews in some of the homes through her work at the Archaeology Field School of the SMU-in-Taos campus of Southern Methodist University. They’ve unearthed children’s artifacts up to 100 years old, including pieces of clay toys, tea sets, doll parts, clothing, mechanical trains, jacks, marbles, child-care implements, modern plastic Legos, Barbie doll parts, action figures and jewelry.

Eiselt’s interest in childhood artifacts is unique because children are rarely documented in archaeological narratives — particularly in the Spanish borderlands, where they appear as victims of slavery and boarding schools.

Her pilot excavations in 2007 and 2008 revealed patterns that suggest children were integral to the workforce and household economy in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the 1930s, the evidence shows, they were drawn from the workforce into the home and pulled as a consumer into the expanding commercial market as well as into the public education realm, says Eiselt, an SMU anthropology professor.

Now Eiselt is launching the SMU-in-Taos Childhood Archaeology Project — thanks in large part to community relationships and trust formed over the past few years. A systematic and scientific examination of children’s lives will provide new perspectives on the dynamics of Spanish and American occupation of New Mexico, she says.

Now Eiselt is launching the SMU-in-Taos Childhood Archaeology Project — thanks in large part to community relationships and trust formed over the past few years. A systematic and scientific examination of children’s lives will provide new perspectives on the dynamics of Spanish and American occupation of New Mexico, she says.

“When state resources and institutions are aimed at children’s lives, cultures are irrevocably changed,” she says. “We’re asking, ‘What can the archaeology of children tell us about the transformation of Hispanic Rio Grande communities over time?'” We’re investigating the impact of state expansion on child-rearing and education in the Spanish borderlands by examining childhood on the Ranchos de Taos Plaza.”

The Ranchos de Taos artifacts bear witness to changes the community has undergone over the past 200 years, she says. Settled by the Spanish in 1716, Ranchos de Taos ultimately absorbed many aspects of Anglo culture. The Catholic grade schools eventually closed, and Hispanic children were forced into the public school system.

The Ranchos de Taos artifacts bear witness to changes the community has undergone over the past 200 years, she says. Settled by the Spanish in 1716, Ranchos de Taos ultimately absorbed many aspects of Anglo culture. The Catholic grade schools eventually closed, and Hispanic children were forced into the public school system.

“What we’ve learned so far is that as you go back in time children are harder to see because you don’t have the inundation of commercial toys,” Eiselt says. “During the Depression Era the plaza is fairly active. We see a lot of communal games like jacks that kids play together. Later in the ’60s and ’70s we see more toys that are individually based and that promote individual play.”

Now Eiselt has the blessing of Ranchos de Taos adults who are interested in their history and anxious to preserve their heritage. The plan is to include children in grades K-12 in the project with fully integrated activities such as oral history interviews, photographs, history education and hands-on excavating. Besides archaeological survey and excavation, Eiselt is digging through files at the state historical archives in Santa Fe. There she’s gathering clues about everything from riddles and toys to customs and education.

The Childhood Archaeology Project also will include analysis of images made by Works Progress Administration photographer John Collier Jr., who chronicled the Great Depression. Many of his photos are on exhibit at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology.

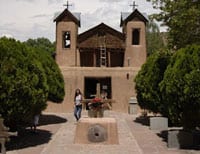

While excavation and research progresses, service projects in the local community also will continue as they have the past few years. University students at the field school work closely with property owners. Each summer 30 undergraduates engage in three weeks of hard labor to re-plaster the historic San Francisco de Asis, a church that’s not only venerated locally by its parishioners but also appreciated worldwide as a unique architectural monument.

While excavation and research progresses, service projects in the local community also will continue as they have the past few years. University students at the field school work closely with property owners. Each summer 30 undergraduates engage in three weeks of hard labor to re-plaster the historic San Francisco de Asis, a church that’s not only venerated locally by its parishioners but also appreciated worldwide as a unique architectural monument.

“It shows our commitment to the community. The people understand we’re not here to exploit the children. Your hands really become part of this church,” Eiselt says. “More and more archaeologists are having to work in communities — not just in remote places. So we’re working with the descendants of the people we’re studying. It’s much more dynamic. The secret to this kind of archaeology is you don’t try to control it. You have to step back and let it unfold.”

Some of the village’s historical traditions include the deeply religious folk society of men called Los Hermanos Penitentes. Pervasive in New Mexico in the 1800s, members of the society carried crosses and flagellated themselves to atone for their sins. Public until almost the turn of the 19th century, the society was forced underground when Catholic clergy increasingly frowned on their practices.

“The student archaeologists have earned the trust of this lay brotherhood sufficiently to be invited to excavate a morada. These are the chapels where many of their rituals take place and so this is a great honor for us,” says Eiselt. Work begins next year in tandem with the Childhood Project. — Margaret Allen

Related links:

Childhood Archaeology Project

Sunday Eiselt and her research

Sunday Eiselt brief bio

SMU’s Archaeology Field School

SMU-in-Taos

![]() Video: SMU-in-Taos

Video: SMU-in-Taos

Student Adventures Blog: Students blog about their experiences at SMU-in-Taos

SMU’s Department of Anthropology

Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences

Precedent for America’s move toward restitution for human rights abuses

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date September 9, 2009

A growing global movement to apologize and make restitution to victims of human rights abuses is now gathering steam in the United States, but it won’t be a first for the country, says the president of The Western History Association.

“In reviewing the history of reconciliation in the American West, I’ve found three examples of government restitution — where we acknowledge we’ve participated in human rights abuses and offered either an apology, restitution, reparation or all three,” says Sherry Smith, associate director of the Clements Center for Southwest Studies at SMU and an SMU history professor.

|

| Sherry Smith, SMU history professor |

The state of Montana granted posthumous pardons to Germans and Austrians convicted and imprisoned under repressive sedition laws during World War I; the U.S. government paid reparations to the heirs of Japanese Americans relocated to incarceration camps during World War II; and in a landmark native-lands case, Arizona returned 6,000 acres to the Hualapai tribe in the 1940s and the U.S. government set up the Indian Claims Commission.

“These are tiny steps considering the magnitude of the problem. But they helped turn the corner of deep injustice,” Smith says. “It’s never too late to do the right thing.”

The global move toward reparations and restitution has largely evolved since World War II, beginning with Germany after the Holocaust, Smith says. Since then other nations and some private corporations have apologized or offered reparations to reconcile the past.

Increasingly, governments are responding to victims’ rights groups that are demanding reconciliation and restitution for slavery, war crimes and other institutionalized abuse.

Most recently, the U.S. Senate in June passed a resolution apologizing for slavery — although it didn’t offer any monetary reparation.

|

| Navajo Indian mother and children in door of hogan. Credit: David deHarport, Natl Park Service Historic Photo Collection |

“The United States is in the beginning stages of this movement,” says Smith, noting that historians have been a critical part of the process as they collect victims’ testimony and verify abuses through documentation.

“To the extent reconciliation includes chronicling and teaching the sometimes troubled past, historians are central to that,” says Smith.

While Smith isn’t drawing moral or ethical conclusions, she did say “the work that historians do can have social justice implications. We need to tell the stories of abuse and keep retelling them as part of the reconciliation process. But victims also need more than words. They want acts, too.”

)

Smith will address “Reconciliation and Restitution in the American West” at the Western History Association’s annual conference in October in Denver. More than 900 association members from museums, universities and government agencies attend the conference. — Margaret Allen

News coverage of Smith’s analysis:

Physorg.com

Science Codex

Medical News Today

Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News

R&D Magazine

ScienceBlog

Related links:

Sherry Smith

The Japanese American Legacy Project

The Montana Sedition Project

Annenberg Public Policy Center: Slavery reparations?

The Western History Association

Clements Center for Southwest Studies

The Archaeology Channel interviews SMU’s Fred Wendorf

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date July 16, 2009

The remarkable 60-year-career of internationally recognized field archaeologist Fred Wendorf, SMU Henderson-Morrison Professor of Prehistory Emeritus, is the subject of an interview with Richard Pettigrew, president and executive director of the nonprofit Archaeological Legacy Institute.

The remarkable 60-year-career of internationally recognized field archaeologist Fred Wendorf, SMU Henderson-Morrison Professor of Prehistory Emeritus, is the subject of an interview with Richard Pettigrew, president and executive director of the nonprofit Archaeological Legacy Institute.

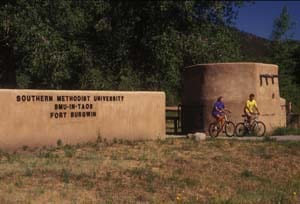

Pettigrew interviewed Wendorf for The Archaeology Channel, exploring Wendorf’s productive career: Founding the Fort Burgwin Research Center in New Mexico, now The Archaeological Field School at SMU-in-Taos; founding SMU’s Department of Anthropology; and leading the Combined Prehistoric Expedition in the Sahara Desert from 1962 to 1999, the longest international prehistoric expedition in northeastern Africa.

A collection of artifacts from the expedition are housed in The Wendorf Collection of The British Museum.

Excerpt:

Dr. Fred Wendorf came of age and began his career during a formative period in American archaeology. But after leaving his permanent mark on the development of archaeology in the American Southwest and the United States, he essentially founded the study of the prehistoric eastern Sahara, beginning with the Aswan Dam Project in the Nile River Valley.

His life, nearly ended by a bullet on a WWII battlefield in Italy, has included an archaeological research career spanning six decades and an unsurpassed record of seminal contributions.

His recently published book, Desert Days: My Life as a Field Archaeologist, is a record not only of a life, but of an epoch in the history of archaeology on two continents.

This is history he not just witnessed, but to a significant degree he created it through his innovative approaches and endless energy, which should serve as an inspiration to subsequent generations of archaeologists.

Dr. Richard Pettigrew of ALI interviewed Dr. Wendorf for The Archaeology Channel on two separate occasions, first in person at the Society for American Archaeology Conference in Atlanta on April 24, 2009, and then over the telephone on June 9, 2009.

Guided by Dr. Wendorf’s book, this interview covers a wide array of topics, including his role in the creation of the first truly large contract archaeology projects in the United States, his momentous and very fruitful decision to launch a field expedition in the Nile River Valley against the wishes and advice of others, and the contributions of his research toward the understanding of human cultural development.

Personal anecdotes combine with long considered assessments to paint a genuine picture of his life and career and the era they have spanned.

Related links:

Anthropology.net: Fred Wendorf

The British Museum: The Wendorf collection

Wendorf an archeological Midas

Desert Days: My Life as a field archaeologist

Prehistoric sites in Egypt and Sudan (By Fred Wendorf)

SMU-in-Taos

The Archaeology Field School at SMU-in-Taos

SMU Clements Center for Southwest Studies

SMU’s Department of Anthropology

Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences

New research partnership at The Archaeology Field School at SMU-in-Taos

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date July 15, 2009

The Archaeology Field School at SMU-in-Taos begins a unique education and research partnership this summer with students and faculty from Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pa., uniting two of the nation’s leading archaeology programs on Southern Methodist University’s New Mexico campus.

“This collaboration will create one of the strongest archaeology field training programs in the nation, if not the world,” said Mike Adler, SMU-in-Taos executive director. “It leverages the strengths of both institutions.”

The goal of the Taos Collaborative Archaeology Program (TCAP) is to unite the strengths of SMU’s community-based archaeology and Mercyhurst’s excavation, documentation and analytical protocols to offer students an unparalleled archaeological training experience.

The goal of the Taos Collaborative Archaeology Program (TCAP) is to unite the strengths of SMU’s community-based archaeology and Mercyhurst’s excavation, documentation and analytical protocols to offer students an unparalleled archaeological training experience.

The SMU-in-Taos campus is sited on an archaeological treasure trove in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains within the Carson National Forest. Program participants have ready access to the restored Fort Burgwin, a pre-Civil War U.S. Cavalry cantonment, and the 13th-century Pot Creek Pueblo. The campus is located on New Mexico Highway 518 between Ranchos de Taos and Penasco. Open archaeological excavations on the SMU-in-Taos campus include the Laundresses Quarters.

The first TCAP session was June 1 through July 15, and joined 12 students from SMU with 16 from Mercyhurst. SMU’s TCAP director is Sunday Eiselt, assistant professor of anthropology, and Mercyhurst field directors are Judith Thomas, a historic archeologist, and Joseph Yedlowski, a prehistoric archeologist.

The first TCAP session was June 1 through July 15, and joined 12 students from SMU with 16 from Mercyhurst. SMU’s TCAP director is Sunday Eiselt, assistant professor of anthropology, and Mercyhurst field directors are Judith Thomas, a historic archeologist, and Joseph Yedlowski, a prehistoric archeologist.

SMU is now in its fourth decade of offering field archaeology at the Taos campus, and Adler estimates more than 1,000 undergraduate and graduate students have trained there.

“We have a lot to learn from each other,” Thomas said. “SMU is very strong in community-based archaeology and they have a top facility at which to study. We provide an intense, hands-on field archaeology experience using state-of-the art technology.”

The Mercyhurst group is supplying a new remote sensing device known as a gladiometer that works in tandem with computer software to detect features and structures buried at shallow depths, to generate subsurface maps and to better target excavation efforts.

The Mercyhurst group is supplying a new remote sensing device known as a gladiometer that works in tandem with computer software to detect features and structures buried at shallow depths, to generate subsurface maps and to better target excavation efforts.

The students will excavate at the Ranchos de Taos Plaza in the shadow of the historic San Francisco de Asis church, and in the homes and backyards of Ranchos de Taos residents whose willingness to work with SMU is a hallmark of the program. Students will also take part in the annual mudding of the church and will record rock art near the spectacular Rio Grande Gorge.

SMU-in-Taos has offered summer education programs tailored to the region’s unique resources since 1973, but the rustic campus dormitories were impractical for use during colder weather. New construction, recent renovations to housing and technological improvements provided through a $4 million lead gift from former Texas Gov. William P. Clements and his wife, Rita, will allow SMU students to take a full semester of classes for the first time this fall.

SMU-in-Taos has offered summer education programs tailored to the region’s unique resources since 1973, but the rustic campus dormitories were impractical for use during colder weather. New construction, recent renovations to housing and technological improvements provided through a $4 million lead gift from former Texas Gov. William P. Clements and his wife, Rita, will allow SMU students to take a full semester of classes for the first time this fall.

Other donors have given more than $1 million to support the student housing. They include Dallas residents Roy and Janis Coffee, Maurine Dickey, Richard T. and Jenny Mullen, Caren H. Prothro and Steve and Marcy Sands; Bill Armstrong and Liz Martin Armstrong of Denver; Irene Athos and the late William J. Athos of St. Petersburg, Fla.; Jo Ann Geurin Thetford of Graham, Texas; and Richard Ware and William J. Ware of Amarillo, Texas. — Kim Cobb (Mercyhurst College contributed to this report)

Related links:

SMU-in-Taos

The Archaeology Field School at SMU-in-Taos

Sunday Eiselt

SMU’s Department of Anthropology

Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences