Research focuses on new tools that enable making materials for chemical detection, tissue engineering and electronics

SMU chemist Nicolay (Nick) Tsarevsky has received a prestigious National Science Foundation CAREER Award, expected to total $650,000 over five years, to fund his research into new methods of creating polymers — whose uses range from fluorescent materials to drug carriers, to everyday technologies.

NSF CAREER Awards are given to tenure-track faculty members who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through outstanding research, excellent education and the integration of education and research in American colleges and universities.

Tsarevsky, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry in SMU’s Dedman College of Humanities and Science, is a polymer chemist and the adviser to seven doctoral students who assist in his research. Polymers are molecules that can be found in just about anything and include both natural and synthetic materials. DNA and proteins are natural polymers, as is the cellulose found in wood and paper. Plastics are a group of synthetic polymers, as are many of the materials used in modern electronic technology. As the slogan for Tsarevsky’s lab group says, “It’s a polymer world…”

Prior to 20 years ago, the lab techniques used to make polymers with any precision approaching that of nature were very limited or didn’t exist. The Tsarevsky group specializes in developing methods to make large polymeric molecules in a lab with desired shapes, sizes and functionalities.

“We try to provide the tools, which can be used to prepare a vast number of complex functional materials,” says Tsarevsky, who, in a nod to history’s Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages, refers to our era as the ‘Polymer Age.’

“We make polymers that have the ability to kill bacteria on contact, and self-healing materials that you could break and that would heal by themselves,” Tsarevsky adds. “I like to think of our work as trying to design and control the architecture of very large molecules.”

Polymer research taps less toxic compounds and those with weaker bonds

To make complex macromolecules, Tsarevsky took advantage of the special behavior (reactivity) of a group of compounds that contain hypervalent chemical bonds. These bonds are weaker than other “classical” chemical bonds, and can be broken in two different ways as well as reconstructed. The atoms they connect can be “swapped” or exchanged — think building with Legos instead of permanent glue — enabling the construction of new materials that couldn’t be made otherwise. Several elements in the Periodic Table are able to form hypervalent bonds, but Tsarevsky feels iodine is one of the most attractive, in part because it’s less toxic than many alternatives.

Many of the current methods for making polymers use toxic heavy metals. The toxic impurities present in the final materials must be removed at potentially significant expense. The hypervalent iodine compounds Tsarevsky is employing aren’t just less toxic, they also allow for processes to be carried out using fewer steps than traditional methods to yield the final functional products. Another chemical element that also is promising for its diverse chemistry (including ability to form hypervalent bonds) and lack of toxicity is bismuth, which Tsarevsky would like to explore in his future research.

“The NSF CAREER funding is absolutely essential,” Tsarevsky says. “Some of the money will go to support doctoral students conducting the research, some will go to support supplies or equipment. Without this support, it would be extremely difficult or impossible to do these studies.”

Desire to show students that chemistry is beautiful, inspiring, allows creativity

Tsarevsky’s long-term educational goal is to increase interest in chemistry, a subject he says too many students are intimidated by.

“It’s only scary when you know nothing about it or when you had a bad teacher in school who made chemistry torture,” Tsarevsky says. “Without chemistry, we wouldn’t have pharmaceuticals or materials like plastics. We wouldn’t have many pigments or paints. Chemistry is not scary – it is beautiful and inspiring and allows you to be creative and make useful things nobody has seen before.”

Tsarevsky joined SMU in 2010. He was a chief science officer at ATRP Solutions, Inc., from 2007-10 and a visiting assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon University from 2005-07. Tsarevsky received a Ph.D. in chemistry from Carnegie Mellon University in 2005 and a Bachelor and Master of Science in theoretical chemistry and chemical physics from the University of Sofia, Bulgaria in 1999. — Kenneth Ryan

Follow SMUResearch.com on twitter at @smuresearch.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Fermilab experiment observes change in neutrinos from one type to another over 500 miles

Fermilab experiment observes change in neutrinos from one type to another over 500 miles Large genome-scale study finds Native American ancestors arrived in single migration wave

Large genome-scale study finds Native American ancestors arrived in single migration wave $3.78 million awarded by Department of Defense to SMU STEM project for minority students

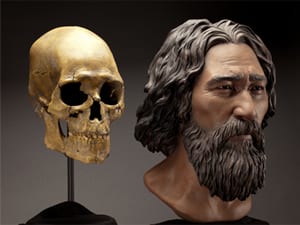

$3.78 million awarded by Department of Defense to SMU STEM project for minority students Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy

Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy At peak fertility, women who desire to maintain body attractiveness report they eat less

At peak fertility, women who desire to maintain body attractiveness report they eat less SMU seismology team to cooperate with state, federal scientists in study of May 7 Venus, Texas earthquake

SMU seismology team to cooperate with state, federal scientists in study of May 7 Venus, Texas earthquake 1st proton collisions at the world’s largest science experiment expected to start the first or second week of June

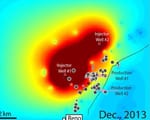

1st proton collisions at the world’s largest science experiment expected to start the first or second week of June Most likely cause of 2013-14 earthquakes: Combination of gas field fluid injection, removal

Most likely cause of 2013-14 earthquakes: Combination of gas field fluid injection, removal