“His foot and ankle mechanics into the ground (which are crucial variable for force application and speed) seem excellent based on the available information, but could potentially be more forceful with modest adjustments,” Weyand said.

Journalist Kelly Dickerson referenced the research of SMU biomechanics expert Peter Weyand for an article in the news blog Science.Mic examining the potential for humans to continue improving strength and speed beyond what has already been achieved.

Dickerson quotes Weyand for his expertise on the mechanics of running and speed of world-class sprinters like Usain Bolt. The article “Usain Bolt’s Winning Race at the Rio Olympics, Explained by Science” published Aug. 15, 2016.

Weyand, director of the SMU Locomotor Performance Laboratory, is one of the world’s leading scholars on the scientific basis of human performance. His research on runners, specifically world-class sprinters, looks at the importance of ground forces for running speed, and has established a contemporary understanding that spans the scientific and athletic communities.

In particular, Weyand’s finding that speed athletes are not able to reposition their legs more rapidly than non-athletes debunked a widespread belief. Rather, Weyand and his colleagues have demonstrated sprinting performance is largely set by the force with which one presses against the ground and how long one applies that force.

Weyand is Glenn Simmons Centennial Chair in Applied Physiology and professor of biomechanics in the Department of Applied Physiology and Wellness in SMU’s Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development.

EXCERPT:

By Kelly Dickerson

Science.mic

Sprinter Usain Bolt of Jamaica just made history by winning his third straight gold medal in the men’s 100-meter dash — something no runner has done before.How does Bolt keep doing it?

Bolt doesn’t win by moving his legs faster than everyone else. At the Olympic level, there are much more important factors that contribute to speed, and Bolt has figured out how to capitalize on them.

The key to sprinting isn’t a quicker stride, according to research by Peter Weyand, a professor of applied physiology and biomechanics at Southern Methodist University. It comes down to the amount of force a runner can apply to the ground, as well as how long they leave their feet on the ground per step.

Case in point: Studies have found the average runner applies about 500 to 600 pounds per step. An Olympic runner applies upward of 1,000 pounds. The average runner has their foot on the ground for 0.12 seconds per step, according to the Post Game. An Olympic runner has it there for less than a tenth of a second.

Bolt is really tall — he stands at 6 feet, 5 inches. Normally, that height would be a disadvantage, Weyand explained.

“Shorter individuals are advantaged coming out of the blocks and over the initial 5 to about 15 meters of the race,” Weyand said in an email. “Shorter runners have less mass to move, so the ground force needed to accelerate the body is not as great. So although Bolt is not the best starter in the world, he loses relatively little ground versus what science indicates he should.”

“Although Bolt is not the best starter in the world, he loses relatively little ground versus what science indicates he should.”

After the start of the race, Bolt’s height becomes a major advantage for two reasons, according to Weyand:

Follow SMU Research on Twitter, @smuresearch.

For more SMU research see www.smuresearch.com.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information, www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

New look at Pizarro’s conquest of Inca reveals foot soldiers were awed by empire’s grandeur

New look at Pizarro’s conquest of Inca reveals foot soldiers were awed by empire’s grandeur Charity, social justice and earth-friendly activism replace big houses, diamond rings and ostentatious living for status seekers

Charity, social justice and earth-friendly activism replace big houses, diamond rings and ostentatious living for status seekers Geohazard: Giant sinkholes near West Texas oil patch towns are growing — as new ones lurk

Geohazard: Giant sinkholes near West Texas oil patch towns are growing — as new ones lurk Wildfire on warming planet requires adaptive capacity at local, national, int’l scales

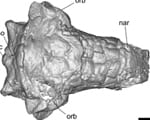

Wildfire on warming planet requires adaptive capacity at local, national, int’l scales Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger

Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data

SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns

Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple

Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought

Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought