Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of Ranchos de Taos in northern New Mexico.

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of Ranchos de Taos in northern New Mexico.

The plaza, once a hub of village life in Ranchos de Taos, these days is notably absent of children. Their families have been driven to the outskirts of the Catholic village by a booming tourism industry that has pushed up property values.

But the children left their mark, says archaeologist Sunday Eiselt, who for three years has led digging crews in some of the homes through her work at the Archaeology Field School of the SMU-in-Taos campus of Southern Methodist University. They’ve unearthed children’s artifacts up to 100 years old, including pieces of clay toys, tea sets, doll parts, clothing, mechanical trains, jacks, marbles, child-care implements, modern plastic Legos, Barbie doll parts, action figures and jewelry.

Eiselt’s interest in childhood artifacts is unique because children are rarely documented in archaeological narratives — particularly in the Spanish borderlands, where they appear as victims of slavery and boarding schools.

Her pilot excavations in 2007 and 2008 revealed patterns that suggest children were integral to the workforce and household economy in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the 1930s, the evidence shows, they were drawn from the workforce into the home and pulled as a consumer into the expanding commercial market as well as into the public education realm, says Eiselt, an SMU anthropology professor.

Now Eiselt is launching the SMU-in-Taos Childhood Archaeology Project — thanks in large part to community relationships and trust formed over the past few years. A systematic and scientific examination of children’s lives will provide new perspectives on the dynamics of Spanish and American occupation of New Mexico, she says.

Now Eiselt is launching the SMU-in-Taos Childhood Archaeology Project — thanks in large part to community relationships and trust formed over the past few years. A systematic and scientific examination of children’s lives will provide new perspectives on the dynamics of Spanish and American occupation of New Mexico, she says.

“When state resources and institutions are aimed at children’s lives, cultures are irrevocably changed,” she says. “We’re asking, ‘What can the archaeology of children tell us about the transformation of Hispanic Rio Grande communities over time?'” We’re investigating the impact of state expansion on child-rearing and education in the Spanish borderlands by examining childhood on the Ranchos de Taos Plaza.”

The Ranchos de Taos artifacts bear witness to changes the community has undergone over the past 200 years, she says. Settled by the Spanish in 1716, Ranchos de Taos ultimately absorbed many aspects of Anglo culture. The Catholic grade schools eventually closed, and Hispanic children were forced into the public school system.

The Ranchos de Taos artifacts bear witness to changes the community has undergone over the past 200 years, she says. Settled by the Spanish in 1716, Ranchos de Taos ultimately absorbed many aspects of Anglo culture. The Catholic grade schools eventually closed, and Hispanic children were forced into the public school system.

“What we’ve learned so far is that as you go back in time children are harder to see because you don’t have the inundation of commercial toys,” Eiselt says. “During the Depression Era the plaza is fairly active. We see a lot of communal games like jacks that kids play together. Later in the ’60s and ’70s we see more toys that are individually based and that promote individual play.”

Now Eiselt has the blessing of Ranchos de Taos adults who are interested in their history and anxious to preserve their heritage. The plan is to include children in grades K-12 in the project with fully integrated activities such as oral history interviews, photographs, history education and hands-on excavating. Besides archaeological survey and excavation, Eiselt is digging through files at the state historical archives in Santa Fe. There she’s gathering clues about everything from riddles and toys to customs and education.

The Childhood Archaeology Project also will include analysis of images made by Works Progress Administration photographer John Collier Jr., who chronicled the Great Depression. Many of his photos are on exhibit at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology.

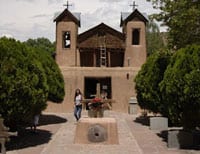

While excavation and research progresses, service projects in the local community also will continue as they have the past few years. University students at the field school work closely with property owners. Each summer 30 undergraduates engage in three weeks of hard labor to re-plaster the historic San Francisco de Asis, a church that’s not only venerated locally by its parishioners but also appreciated worldwide as a unique architectural monument.

While excavation and research progresses, service projects in the local community also will continue as they have the past few years. University students at the field school work closely with property owners. Each summer 30 undergraduates engage in three weeks of hard labor to re-plaster the historic San Francisco de Asis, a church that’s not only venerated locally by its parishioners but also appreciated worldwide as a unique architectural monument.

“It shows our commitment to the community. The people understand we’re not here to exploit the children. Your hands really become part of this church,” Eiselt says. “More and more archaeologists are having to work in communities — not just in remote places. So we’re working with the descendants of the people we’re studying. It’s much more dynamic. The secret to this kind of archaeology is you don’t try to control it. You have to step back and let it unfold.”

Some of the village’s historical traditions include the deeply religious folk society of men called Los Hermanos Penitentes. Pervasive in New Mexico in the 1800s, members of the society carried crosses and flagellated themselves to atone for their sins. Public until almost the turn of the 19th century, the society was forced underground when Catholic clergy increasingly frowned on their practices.

“The student archaeologists have earned the trust of this lay brotherhood sufficiently to be invited to excavate a morada. These are the chapels where many of their rituals take place and so this is a great honor for us,” says Eiselt. Work begins next year in tandem with the Childhood Project. — Margaret Allen

Related links:

Childhood Archaeology Project

Sunday Eiselt and her research

Sunday Eiselt brief bio

SMU’s Archaeology Field School

SMU-in-Taos

![]() Video: SMU-in-Taos

Video: SMU-in-Taos

Student Adventures Blog: Students blog about their experiences at SMU-in-Taos

SMU’s Department of Anthropology

Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of

Old restored homes — gentrified with galleries, shops and restaurants — ring the historic and picturesque plaza of