Leading standardized equations used to predict or estimate walking energy expenditure — calories burned — count too few calories in nearly all cases on level surfaces, study finds. New method improves accuracy.

Walking is the most common exercise, and many walkers like to count how many calories are burned.

Little known, however, is that the leading standardized equations used to predict or estimate walking energy expenditure — the number of calories burned — assume that one size fits all. The equations have been in place for close to half a century and were based on data from a limited number of people.

A new study at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, found that under firm, level ground conditions, the leading standards are relatively inaccurate and have significant bias. The standards predicted too few calories burned in 97 percent of the cases researchers examined, said SMU physiologist Lindsay Ludlow.

A new standardized equation developed by SMU scientists is about four times more accurate for adults and kids together, and about two to three times more accurate for adults only, Ludlow said.

“Our new equation is formulated to apply regardless of the height, weight and speed of the walker,” said Ludlow, a researcher in the SMU Locomotor Performance Laboratory of biomechanics expert Peter Weyand. “And it’s appreciably more accurate.”

Ludlow and her colleagues report the new equation in the Journal of Applied Physiology, “Energy expenditure during level human walking: seeking a simple and accurate predictive solution.” The article is published in the March 1, 2016 issue, and available online at this link.

“The economy of level walking is a lot like shipping packages – there is an economy of scale,” said Weyand, a co-author on the paper. “Big people get better gas mileage when fuel economy is expressed on a per-pound basis.”

The SMU equation predicts the calories burned as a person walks on a firm, level surface. Ongoing research is expanding the algorithm to predict the calories burned while walking up- and downhill, and while carrying loads, Ludlow said.

SMU’s research is funded by the U.S. Department of Defense Medical Research and Materiel Command. The grant is part of a larger DOD effort to develop load-carriage decision-aid tools to assist foot soldiers.

The research comes at a time when greater accuracy combined with mobile technology, such as wearable sensors like Fitbit, is increasingly being used in real time to monitor the body’s status. The researchers note that some devices use the old standardized equations, while others use a different method to estimate the calories burned.

New equation considers different-sized people

To provide a comprehensive test of the leading standards, SMU researchers compiled a database using the extensive walking metabolism data available in the existing scientific literature to evaluate the leading equations for walking on level ground.

“The SMU approach improves upon the existing standards by including different-sized individuals and drawing on a larger database for equation formulation,” Weyand said.

The new equation achieves greater accuracy by better incorporating the influence of body size, and by specifically incorporating the influence of height on gait mechanics. Specifically:

- Bigger people burn fewer calories on a per pound basis of their body weight to walk at a given speed or to cover a fixed distance;

- The older standardized equations don’t account for size differences well, assuming roughly that one size fits all.

Accuracy of standardized equations had not previously undergone comprehensive evaluation

The exact dates are a bit murky, but the leading standardized equations, known by their shorthand as the “ACSM” and “Pandolf” equations, were developed about 40 years ago for the American College of Sports Medicine and for the military, Ludlow said.

The Pandolf method, for example, draws on walking metabolism data from six U.S. soldiers, she said. Both the Pandolf and ACSM equations were developed on a small number of adult males of average height.

The new more accurate equation will prove useful. Predicting energy expenditure is common in many fields, including those focused on health, weight loss, exercise, military and defense, and professional and amateur physical training.

“Burning calories is of major importance to health, fitness and the body’s physiological status,” Weyand said. “But it hasn’t been really clear just how accurate the existing standards are under level conditions because previous assessments by other researchers were more limited in scope.”

Energy expenditure estimates could assist with monitoring the body’s physiological status

Accurate estimations of the rate at which calories are burned could potentially help predict a person’s aerobic power and likelihood for executing a task, such as training for an athletic competition or carrying out a military objective.

In general, the new metabolic estimates can be combined with other physiological signals such as body heat, core temperature and heart rate to improve predictions of fatigue, overheating, dehydration, the aerobic power available, and whether a person can sustain a given intensity of exercise.

Military seeks solutions to overburdened soldier problem

The military has a major interest in more accurate techniques to help address their problem of over-burdened soldiers.

“These soldiers carry incredible loads — up to 150 pounds, but they often need to be mobile to successfully carry out their missions,” said Weyand, a professor of Applied Physiology and Wellness in the SMU Simmons School of Education.

Accurately predicting how many calories a person expends while walking could supply information that can help soldiers avoid thermal stress and fatigue in the field, especially troops deployed to challenging environments.

“Soldiers incur a variety of physiological and musculoskeletal stresses in the field,” Weyand said. “Our metabolic modeling work is part of a broader effort to provide the Department of Defense with quantitative tools to help soldiers.” — Margaret Allen

Follow SMUResearch.com on twitter at @smuresearch.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

New look at Pizarro’s conquest of Inca reveals foot soldiers were awed by empire’s grandeur

New look at Pizarro’s conquest of Inca reveals foot soldiers were awed by empire’s grandeur Charity, social justice and earth-friendly activism replace big houses, diamond rings and ostentatious living for status seekers

Charity, social justice and earth-friendly activism replace big houses, diamond rings and ostentatious living for status seekers National Center for Arts Research white paper counters findings of the Devos Institute Study on Culturally Specific Arts Organizations

National Center for Arts Research white paper counters findings of the Devos Institute Study on Culturally Specific Arts Organizations Long-term daily contact with Spanish missions triggered collapse of Native American populations in New Mexico

Long-term daily contact with Spanish missions triggered collapse of Native American populations in New Mexico North America’s newest pterosaur is a Texan — and flying reptile’s closest cousin is English

North America’s newest pterosaur is a Texan — and flying reptile’s closest cousin is English California 6th grade science books: Climate change a matter of opinion not scientific fact

California 6th grade science books: Climate change a matter of opinion not scientific fact Reading ability soars if young struggling readers get school’s intensive help immediately

Reading ability soars if young struggling readers get school’s intensive help immediately

Drugs behave as predicted in computer model of key protein, enabling cancer drug discovery

Drugs behave as predicted in computer model of key protein, enabling cancer drug discovery Researchers discover new drug-like compounds that may improve odds for men battling prostate cancer

Researchers discover new drug-like compounds that may improve odds for men battling prostate cancer Fermilab experiment observes change in neutrinos from one type to another over 500 miles

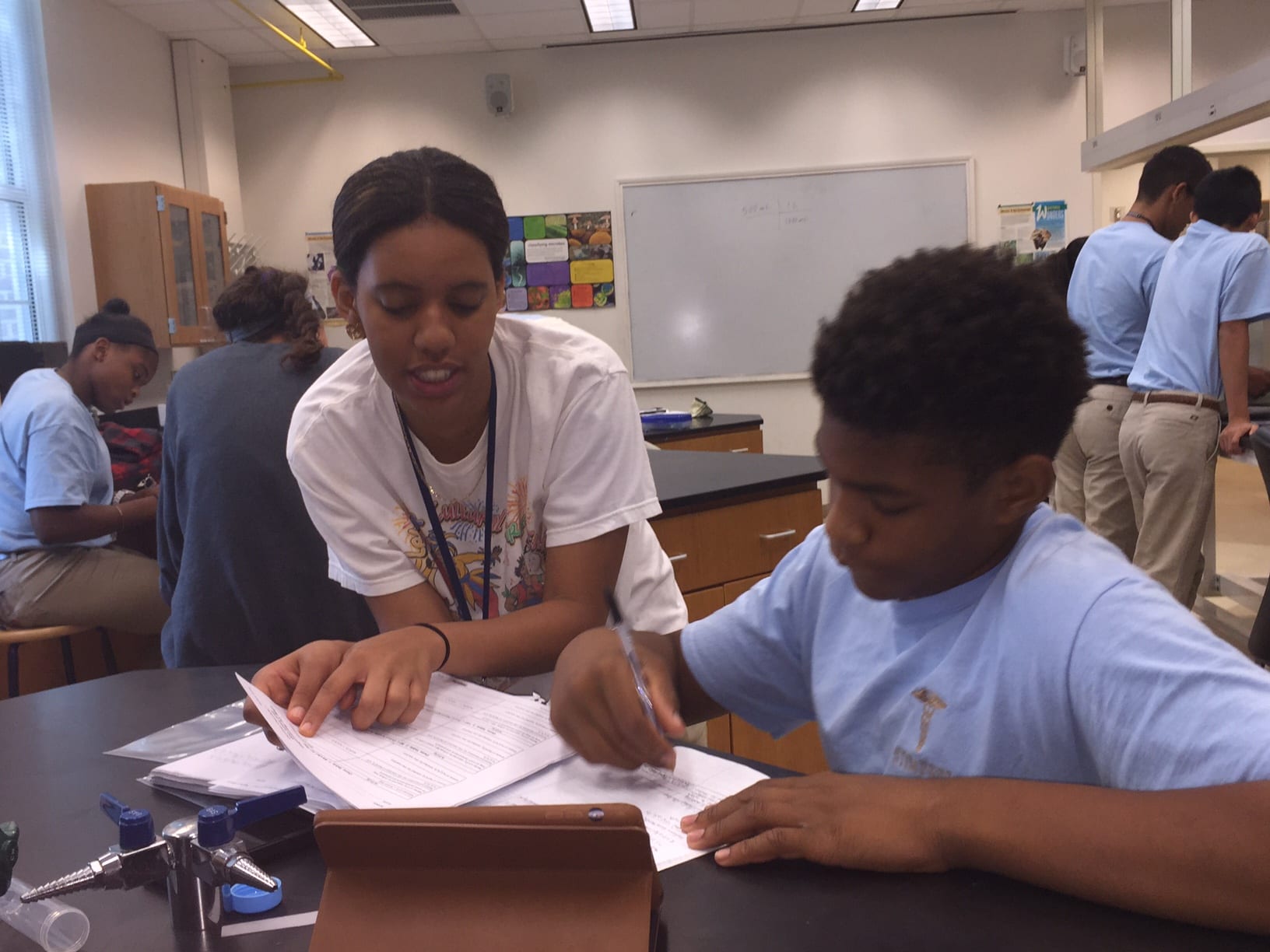

Fermilab experiment observes change in neutrinos from one type to another over 500 miles $3.78 million awarded by Department of Defense to SMU STEM project for minority students

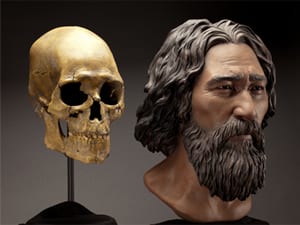

$3.78 million awarded by Department of Defense to SMU STEM project for minority students Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy

Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy At peak fertility, women who desire to maintain body attractiveness report they eat less

At peak fertility, women who desire to maintain body attractiveness report they eat less Physicists tune Large Hadron Collider to find “sweet spot” in high-energy proton smasher

Physicists tune Large Hadron Collider to find “sweet spot” in high-energy proton smasher

Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy

Kennewick Man: genome sequence of 8,500-year-old skeleton solves scientific controversy SMU seismology team to cooperate with state, federal scientists in study of May 7 Venus, Texas earthquake

SMU seismology team to cooperate with state, federal scientists in study of May 7 Venus, Texas earthquake

Most likely cause of 2013-14 earthquakes: Combination of gas field fluid injection, removal

Most likely cause of 2013-14 earthquakes: Combination of gas field fluid injection, removal 17 million-year-old whale fossil provides 1st exact date for East Africa’s puzzling uplift

17 million-year-old whale fossil provides 1st exact date for East Africa’s puzzling uplift SMU analysis of recent North Texas earthquake sequence reveals geologic fault, epicenters in Irving and West Dallas

SMU analysis of recent North Texas earthquake sequence reveals geologic fault, epicenters in Irving and West Dallas Bitcoin scams steal at least $11 million in virtual deposits from unsuspecting customers

Bitcoin scams steal at least $11 million in virtual deposits from unsuspecting customers Teen girls report less sexual victimization after virtual reality assertiveness training

Teen girls report less sexual victimization after virtual reality assertiveness training

Women who are told men desire women with larger bodies are happier with their weight

Women who are told men desire women with larger bodies are happier with their weight Fossil supervolcano in Italian Alps may answer deep mysteries around active supervolcanoes

Fossil supervolcano in Italian Alps may answer deep mysteries around active supervolcanoes Study: Contraception may change how happy women are with their husbands

Study: Contraception may change how happy women are with their husbands Study funded by NIH is decoding blue light’s mysterious ability to alter body’s natural clock

Study funded by NIH is decoding blue light’s mysterious ability to alter body’s natural clock