Usain Bolt, the fastest-ever human, appears to have an extra gear that propels him ahead of other sprinters. But that’s not what’s going on.

Science writer Matthew Futterman tapped the expertise of SMU biomechanics expert Peter Weyand for an article about the world’s fastest-ever human, Usain Bolt.

Reporting in The Wall Street Journal, Futterman quotes Weyand for his expertise on the mechanics of Usain Bolt’s unusual speed. The article “The Science Behind Sprinter Usain Bolt’s Speed,” published July 28, 2016.

Weyand, director of the SMU Locomotor Performance Laboratory, is one of the world’s leading scholars on the scientific basis of human performance. His research on runners, specifically world-class sprinters, looks at the importance of ground forces for running speed, and has established a contemporary understanding that spans the scientific and athletic communities.

In particular, Weyand’s finding that speed athletes are not able to reposition their legs more rapidly than non-athletes debunked a widespread belief. Rather, Weyand and his colleagues have demonstrated sprinting performance is largely set by the force with which one presses against the ground and how long one applies that force.

Weyand is Glenn Simmons Centennial Chair in Applied Physiology and professor of biomechanics in the Department of Applied Physiology and Wellness in SMU’s Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development.

EXCERPT:

By Matthew Futterman

The Wall Street Journal

Sprinters who have taken on Usain Bolt in the 100-meter dash often describe a moment in the second half of the race when the world’s fastest-ever human just runs away from them.One minute they are shoulder-to-shoulder with Bolt, believing that this will be the night the legend will be toppled. The next they are staring at his back, watching him raise his hands in triumph, sometimes many meters before he crosses the finish line.

Last week Bolt expressed his usual, unflappable confidence, even though a hamstring injury kept him from Jamaica’s track and field trials. Granted a medical exemption by the country’s athletics federation, he was named to the team even though he couldn’t qualify at the national trials.

“My chances are always the same: Great!” he said. “If everything goes smoothly the rest of the time and the training goes well, I’m going to be really confident going to the championship.” …

…However, a 2012 study by Matthew Bundle of the University of Montana in Missoula and Peter Weyand at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, showed that the greatest decrease in muscular performance occurs within the first seconds of a sprint when runners are still accelerating, which would suggest that deceleration in a race as short as 100 meters may not be related to how sprinters metabolize glycogen.

“Muscle fatigue happens contraction by contraction,” Weyand said. He argues that the biological process that causes the fatigue is still a mystery. It also is very hard to measure, because it is difficult to examine what is happening to an incredibly fast person’s muscles when he can only run at full speed for roughly three seconds.

Still, the idea that muscle fatigue begins instantaneously and with each muscle contraction may say plenty about why Bolt is so hard to beat.

Follow SMU Research on Twitter, @smuresearch.

For more SMU research see www.smuresearch.com.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information, www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Geohazard: Giant sinkholes near West Texas oil patch towns are growing — as new ones lurk

Geohazard: Giant sinkholes near West Texas oil patch towns are growing — as new ones lurk Wildfire on warming planet requires adaptive capacity at local, national, int’l scales

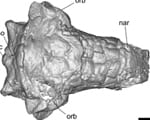

Wildfire on warming planet requires adaptive capacity at local, national, int’l scales Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger

Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data

SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns

Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple

Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought

Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought