Predominant religion in a community affects the decision-making process of mutual fund managers in that community

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Johan Sulaeman in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Related links

More SMU Research news

CNN’s “Belief” blog covered the research of SMU financial economist Johan Sulaeman. In the Sept. 25 article “Study links mutual fund decisions with religion,” CNN journalist Laura Koran reported on research by Sulaeman and others who found that religion plays a major role in many Americans’ lives, including their investing.

“Specifically, the study found that mutual funds located in predominantly Catholic areas are associated with increasing fund volatility, a measure of risk taking, by about 6 percent, compared to those in low-Catholic areas. Those in predominately Protestant counties have a 14 percent lower fund volatility compared with those in low-Protestant areas.”

Sulaemann is an assistant professor of finance in the Cox School of Business.

EXCERPT:

By Laura Koran

CNNFaith plays a major role in many Americans’ lives, affecting their outlook on morality, politics and even – according to a new study – investing.

The study, conducted at the University of Georgia and Southern Methodist University, found that the predominant religion in a community affects the decision-making process of mutual fund managers in that community, specifically when it comes to risk.

Mutual funds in counties with larger Catholic communities tend to embrace risk more than those in majority-Protestant counties, the study found. Earlier studies have found that Catholics are generally more prone to take speculative risks than the average population, while Protestants are more risk-averse than the average population.

The findings, which will be published next month in the academic journal Management Science, could help provoke a re-evaluation of how investing works, its authors said.

“One would expect that with very, very severe competition within the mutual fund industry, culture should play no role in mutual fund decisions because fund managers … should adopt value-maximizing strategies,” said Tao Shu, an assistant professor of finance at the University of Georgia and one of the study’s authors.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with Metin Eren or book him in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

“Surprisingly,” Shu continued, “we found that despite the very intense competition within the mutual fund industry, mutual funds are still impacted by local culture.”

Specifically, the study found that mutual funds located in predominantly Catholic areas are associated with increasing fund volatility, a measure of risk taking, by about 6%, compared to those in low-Catholic areas. Those in predominately Protestant counties have a 14% lower fund volatility compared with those in low-Protestant areas.

The study looked at 1,621 growth and aggressive growth mutual funds.

Shu conducted the study with University of Georgia colleague Eric Yeung and Johan Sulaeman of Southern Methodist University.

SMU is a private university in Dallas where nearly 11,000 students benefit from the national opportunities and international reach of SMU’s seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smuresearch.com. Follow SMU Research on Twitter, @smuresearch.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Salon: What baseball tells us about racism

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date September 30, 2011

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Johan Sulaeman in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

More SMU Research news

Best-selling author, syndicated columnist and progressive talk-radio host David Sirota has covered the research of SMU’s Dr. Johan Sulaeman, an expert in labor economics and discrimination. The article published in the Sept. 30 issue of Salon. Other places it published include Truthout, Denver Post, Nation of Change and Tahoe Daily Tribune.

The Sirota article was also picked up and a shortened version published in the Chicago Tribune, “Study: Umpires are definitely not blind.”

An assistant professor of finance in the Cox School of Business, Sulaeman and his co-authors analyzed 3.5 million Major League Baseball pitches and found that racial/ethnic bias by home plate umpires lowers the performance of Major League’s minority pitchers, diminishing their pay compared to white pitchers.

The study found that minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they throw in a way that actually harmed their performance.

Read the full article in Salon.

EXCERPT:

By David Sirota

Salon

Despite recent odes to “post-racial” sensibilities, persistent racial wage and unemployment gaps show that prejudice is alive and well in America. Nonetheless, that truism is often angrily denied or willfully ignored in our society, in part, because prejudice is so much more difficult to recognize on a day-to-day basis. As opposed to the Jim Crow era of white hoods and lynch mobs, 21st century American bigotry is now more often an unseen crime of the subtle and the reflexive — and the crime scene tends to be the shadowy nuances of hiring decisions, performance evaluations and plausible deniability.Thankfully, though, we now have baseball to help shine a light on the problem so that everyone can see it for what it really is.

Today, Major League Baseball games using QuesTec’s computerized pitch-monitoring system are the most statistically quantifiable workplaces in America. Match up QuesTec’s accumulated data with demographic information about who is pitching and who is calling balls and strikes, and you get the indisputable proof of how ethnicity does indeed play a part in discretionary decisions of those in power positions.

This is exactly what Southern Methodist University’s researchers did when they examined more than 3.5 million pitches from 2004 to 2008. Their findings say as much about the enduring relationship between sports and bigotry as they do about the synaptic nature of racism in all of American society.

First and foremost, SMU found that home-plate umpires call disproportionately more strikes for pitchers in their same ethnic group. Because most home-plate umpires are white, this has been a big form of racial privilege for white pitchers, who researchers show are, on average, getting disproportionately more of the benefit of the doubt on close calls.

Second, SMU researchers found that “minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they threw in a way that actually harmed their performance and statistics.” Basically, these hurlers adjusted to the white umpires’ artificially narrower strike zone by throwing pitches down the heart of the plate, where they were easier for batters to hit.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the data suggest that racial bias is probably operating at a subconscious level, where the umpire doesn’t even recognize it.

To document this, SMU compared the percentage of strikes called in QuesTec-equipped ballparks versus non-QuesTec parks. Researchers found that umpires’ racial biases diminished when they knew they were being monitored by the computer.

Read the full article in Salon.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Johan Sulaeman in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

More SMU Research news

Best-selling author, syndicated columnist and progressive talk-radio host David Sirota has covered the research of SMU’s Dr. Johan Sulaeman, an expert in labor economics and discrimination. The article published in the Sept. 30 issue of In These Times.

An assistant professor of finance in the Cox School of Business, Sulaeman and his co-authors analyzed 3.5 million Major League Baseball pitches and found that racial/ethnic bias by home plate umpires lowers the performance of Major League’s minority pitchers, diminishing their pay compared to white pitchers.

The study found that minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they throw in a way that actually harmed their performance.

Read the full article at In These Times.

EXCERPT:

By David Sirota

In These Times

Despite recent odes to “post-racial” sensibilities, persistent racial wage and unemployment gaps show that prejudice is alive and well in America. Nonetheless, that truism is often angrily denied or willfully ignored in our society, in part, because prejudice is so much more difficult to recognize on a day-to-day basis. As opposed to the Jim Crow era of white hoods and lynch mobs, 21st century American bigotry is now more often an unseen crime of the subtle and the reflexive???and the crime scene tends to be the shadowy nuances of hiring decisions, performance evaluations and plausible deniability.Thankfully, though, we now have baseball to help shine a light on the problem so that everyone can see it for what it really is.

Today, Major League Baseball games using QuesTec’s computerized pitch-monitoring system are the most statistically quantifiable workplaces in America. Match up QuesTec’s accumulated data with demographic information about who is pitching and who is calling balls and strikes, and you get the indisputable proof of how ethnicity does indeed play a part in discretionary decisions of those in power positions.

This is exactly what Southern Methodist University’s researchers did when they examined more than 3.5 million pitches from 2004 to 2008. Their findings say as much about the enduring relationship between sports and bigotry as they do about the synaptic nature of racism in all of American society.

First and foremost, SMU found that home-plate umpires call disproportionately more strikes for pitchers in their same ethnic group. Because most home-plate umpires are white, this has been a big form of racial privilege for white pitchers, who researchers show are, on average, getting disproportionately more of the benefit of the doubt on close calls.

Second, SMU researchers found that “minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they threw in a way that actually harmed their performance and statistics.” Basically, these hurlers adjusted to the white umpires’ artificially narrower strike zone by throwing pitches down the heart of the plate, where they were easier for batters to hit.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the data suggest that racial bias is probably operating at a subconscious level, where the umpire doesn’t even recognize it.

To document this, SMU compared the percentage of strikes called in QuesTec-equipped ballparks versus non-QuesTec parks. Researchers found that umpires’ racial biases diminished when they knew they were being monitored by the computer.

Read the full article at In These Times.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Johan Sulaeman in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Best-selling author and progressive talk-radio host David Sirota interviewed SMU’s Dr. Johan Sulaeman, an expert in labor economics and discrimination.

An assistant professor of finance in the Cox School of Business, Sulaeman and his co-authors analyzed 3.5 million Major League Baseball pitches and found that racial/ethnic bias by home plate umpires lowers the performance of Major League’s minority pitchers, diminishing their pay compared to white pitchers.

The study found that minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they throw in a way that actually harmed their performance.

Findings important when measuring the extent of wage discrimination not only in baseball, but also in broader labor market

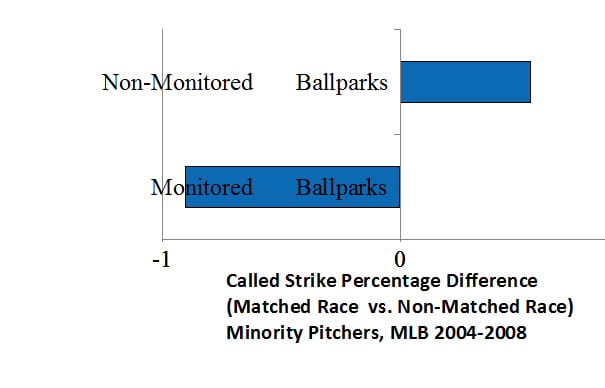

Minority Pitchers

|

| In non-monitored ballparks, minority pitchers facing matched-race umpires will have 0.63% higher called strike probability than if they face non-matched-race umpires. In monitored ballparks, this effect is reversed: minority pitchers facing matched-race umpires will have 1.03% LOWER called strike probability than if they face non-matched-race umpires. (Credit: Sulaeman) |

White Pitchers

| In non-monitored ballparks, white pitchers facing matched-race umpires will have 0.25% higher called strike probability than if they face non-matched-race umpires. In monitored ballparks, white pitchers facing matched-race umpires will have .33% lower called strike probability than if they face non-matched-race umpires. (Credit: Sulaeman) |

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Johan Sulaeman in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Related links

More SMU Research news

When it comes to Major League Baseball’s pitchers, the more strikes, the better. But what if white umpires call strikes more often for white pitchers than for minority pitchers?

New research findings provide an answer. Analysis of 3.5 million pitches from 2004 to 2008 found that minority pitchers scale back their performance to overcome racial/ethnic favoritism toward whites by MLB home plate umpires, said Johan Sulaeman, a financial economist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and a study author.

The study found that minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they throw in a way that actually harmed their performance and statistics, said Sulaeman, a labor and discrimination expert.

Specifically, minority pitchers limited the umpires’ discretion to call their pitch a “ball” by throwing squarely across the plate in the strike zone more often. Unfortunately for the pitcher, such throws are also easier for batters to hit.

The finding builds on an earlier study that discovered Major League Baseball’s home plate umpires called strikes more often for pitchers in their same ethnic group — except when the plate was electronically monitored by cameras, Sulaeman said.

While the earlier finding surprised the researchers, they said, the latest results are even more surprising.

Since most MLB umpires are white, the overall effect is that umpire bias pushes performance measures of minorities downward, said Sulaeman, an expert in labor economics and discrimination.

The findings have important implications for measuring the extent of discrimination not only in baseball, but also in labor markets generally, say the authors.

“In MLB, as in so many other fields of endeavor, power belongs disproportionately to members of the majority — white — group,” the authors write.

Findings draw on analysis of pitching in QuesTec-monitored parks

Sulaeman and his co-authors analyzed 3.5 million pitches by Major League Baseball pitchers from 2004 to 2008. All parks are now monitored, but during those four years about one-third of major league ballparks were monitored with computers and cameras to check the accuracy of the umpires’ ball and strike calls.

Four cameras tracked and recorded the location of each pitch, with umpires and pitchers aware that QuesTec was the primary mechanism for gauging umpire performance. MLB considers an ump’s performance sub-standard if more than 10 percent of his calls differ from QuesTec.

Of the 3.5 million pitches, umpire and pitcher were the same race — usually white — for about two-thirds of the 1.89 million pitches that were called strikes or balls. About 89 percent of umpires and 70 percent of pitchers were white.

The researchers looked not only at the race of umpires, pitchers and batters, but also: effects for each pitcher, umpire and batter; presence or absence of QuesTec; importance of the at-bat; when the pitch would terminate the at-bat; whether the pitch came early or later in the game; importance of the game; racial demographics of the neighborhood around the park; umpire age and experience; pitch characteristics, including horizontal pitch distance and pitch height; and whether the throw was a fastball, curveball, slider or cutter.

The study controlled for inning, pitch count, pitcher score advantage and whether the pitcher was playing at home or visiting.

The study, “Strike Three: Discrimination, Incentives, and Evaluation,” is published in the current issue of the scholarly journal The American Economic Review.

In addition to Sulaeman, co-authors were Christopher A. Parsons, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Michael C. Yates, Auburn University; and Daniel S. Hamermesh, University of Texas at Austin.

Findings: Minimal direct impact, but significant indirect influence

The researchers found:

- In non-monitored parks, the percentage of called pitches that are strikes is higher when the race of both umpire and pitcher match than when it does not. This is true not only of whites, but also Hispanics and blacks.

- In QuesTec parks, if the race of the pitcher and umpire match, the likelihood that a called pitch is ruled a strike is reduced by more than one percentage point relative to the same setup in non-QuesTec parks. This implies umpires implicitly allow their apparent favoritism to be expressed when not being monitored, the study authors say.

- Implicit monitoring — for example, an important pitch viewed by a big crowd — also dramatically alters umpire behavior. On the other hand, white and minority umpires at poorly attended games appear to favor pitchers of the same race by calling more strikes.

- Umpires favor pitchers of the same race only when the pitch won’t terminate the batter’s plate appearance.

- Little evidence was found to indicate the umpire is influenced by the race of either the batter or the catcher.

- A higher strike percentage showed umpires exhibited same-race favoritism in non-QuesTec parks. A lower strike percentage indicated negative bias toward pitchers of different races in QuesTec parks.

- There is some weak evidence that bias is more likely among younger and less experienced umpires.

- Favoritism was a significant factor for pitches thrown to the edge of the strike zone — where umpires have the most discretion — but not for pitches inside or outside the strike zone. In QuesTec parks, the umpire and pitcher having the same race has virtually no effect on pitch location. In non-QuesTec parks, pitches to the edges significantly increase when umpire and pitcher share the same race. The finding suggests pitchers gamble on the fact that this region can reasonably be called as either balls or strikes and therefore offers them an advantage.

- In QuesTec parks, matched race is associated with a slight preference for hard-to-hit and hard-to-call curveball pitches. In non-QuesTec parks, that preference quadruples.

The researchers concluded:

- The direct effects on pitch outcomes are small. The indirect effect on players’ strategies may have larger impacts on the outcomes of plate appearances and games.

- From the starting pitcher’s perspective, a racial match with the umpire helped his statistics by yielding fewer earned runs, fewer hits and fewer home runs.

- Because the majority of umpires are white, teams with minority pitchers have a distinct disadvantage in non-monitored parks.

- There is no evidence that visiting managers adjusted their pitching lineups to minimize exposure of their minority pitchers to the subjective bias of a white umpire.

- In parks without QuesTec, pitchers of the same race threw pitches that allowed umpires the most discretion, apparently to maximize their advantage stemming from the umpires’ favoritism.

- A batter who swings is less likely to get a hit when the umpire and pitcher match.

- Applying the effects of favoritism, and given that the average salary of starting pitchers in MLB was $4.8 million in 2006, the findings suggest minority pitchers were underpaid relative to white pitchers by between $50,000 and $400,000 a year.

“If a pitcher expects favoritism, he will incorporate this advantage into his strategy, perhaps throwing pitches that allow the umpire more discretion,” the authors write. “If the batter expects such pitches to be called strikes, he is forced to swing at worse pitches, which reduces the likelihood of getting a hit.”

Not just Major League Baseball; a factor in all work environments

How many minority pitchers have had their pitching records diminished by this phenomenon is impossible to say, Sulaeman said, adding that one can only guess at the impact over decades of professional baseball. But discovery of the indirect effect of racial bias in MLB pointedly demonstrates how discrimination alters the behavior of a discriminated group, say the authors.

In any workplace where pay is based on measured productivity, the findings of small direct and larger indirect effects of favoritism and negative bias have important implications for measuring the extent of wage discrimination not only in baseball, but also in labor markets generally, say the authors.

Supervisory racial bias must be accounted for when generating measures of wage discrimination, the authors conclude.

The researchers’ earlier analysis of the data found that ethnic bias is virtually eliminated when an umpire knows his calls are being monitored with video cameras to check for accuracy.

“The good news is that all ballparks are now equipped with this technology, likely eliminating this subconscious bias,” said Sulaeman, assistant professor of finance in SMU’s Cox School.

Monitoring suppresses bias when evaluators are observed for bias

That isn’t the case, however, in other workplaces, where monitoring is not the norm, he said. As a result, supervisors have ample opportunity to subconsciously evaluate those of a different race more negatively, he said. Supervisors may be less prone to this subconscious bias if they know they are being monitored.

“When their decisions matter more, and when evaluators are themselves more likely to be evaluated by others, our results suggest that these preferences no longer manifest themselves,” the authors say. — Margaret Allen

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Texas frontier scientists who uncovered state’s fossil history had role in epic Bone Wars

Texas frontier scientists who uncovered state’s fossil history had role in epic Bone Wars Observed! SMU’s LHC physicists confirm new particle; Higgs ‘God particle’ opens new frontier of exploration

Observed! SMU’s LHC physicists confirm new particle; Higgs ‘God particle’ opens new frontier of exploration DOE Award: advancing SMU’s link to the God particle

DOE Award: advancing SMU’s link to the God particle Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual

Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance

Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance Modeling the human protein in search of cancer treatment: SMU Researcher Q&A

Modeling the human protein in search of cancer treatment: SMU Researcher Q&A