Best-selling author and progressive talk-radio host David Sirota interviewed SMU’s Dr. Johan Sulaeman, an expert in labor economics and discrimination.

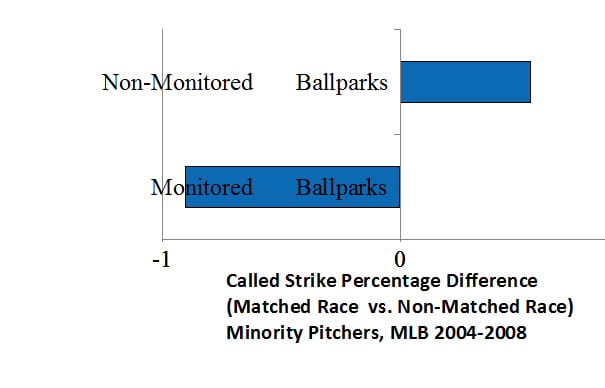

An assistant professor of finance in the Cox School of Business, Sulaeman and his co-authors analyzed 3.5 million Major League Baseball pitches and found that racial/ethnic bias by home plate umpires lowers the performance of Major League’s minority pitchers, diminishing their pay compared to white pitchers.

The study found that minority pitchers reacted to umpire bias by playing it safe with the pitches they throw in a way that actually harmed their performance.