Leakage in Ken Regan field could have contaminated groundwater for livestock and irrigation between 2007 and 2011

DALLAS (SMU) – Geophysicists at SMU say that evidence of leak occurring in a West Texas wastewater disposal well between 2007 and 2011 should raise concerns about the current potential for contaminated groundwater and damage to surrounding infrastructure.

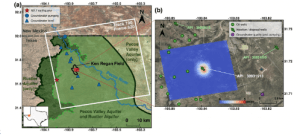

SMU geophysicist Zhong Lu and the rest of his team believe the leak happened at a wastewater disposal well in the Ken Regan field in northern Reeves County, which could have leaked toxic chemicals into the Rustler Aquifer. The same team of geophysicists at SMU has revealed that sinkholes are expanding and forming in West Texas at a startling rate.

Wastewater is a byproduct of oil and gas production. Using a process called horizontal drilling, or “fracking,” companies pump vast quantities of water, sand and chemicals far down into the ground to help extract more natural gas and oil. With that gas and oil, however, come large amounts of wastewater that is injected deep into the earth through disposal wells.

Federal and state oil and gas regulations require wastewater to be disposed of at a deep depth, typically ranging from about 1,000 to 2,000 meters deep in this region, so it does not contaminate groundwater or drinking water. A small number of studies suggest that arsenic, benzene and other toxins potentially found in fracking fluids may pose serious risks to reproductive and development health.

Even though the leak is thought to have happened between 2007 and 2011, the finding is still potentially dangerous, said Weiyu Zheng, a Ph.D. student at SMU (Southern Methodist University) who led the research.

“The Rustler Aquifer, within the zone of the effective injection depth, is only used for irrigation and livestock but not drinking water due to high concentrations of dissolved solids. Wastewater leaked into this aquifer may possibly contaminate the freshwater sources,” Zheng explained.

“If I lived in this area, I would be a bit worried,” said Lu, professor of Shuler-Foscue Chair at SMU’s Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences and the corresponding researcher of the findings.

He also noted that leaking wastewater can do massive damage to surrounding infrastructure. For example, oil and gas pipelines can be fractured or damaged beneath the surface, and the resulting heaving ground can damage roads and put drivers at risk.

SMU geophysicists say satellite radar imagery indicates a leak in the nearby disposal well happened because of changes shown to be happening in the nearby Ken Regan field: a large section of ground, five football fields in diameter and about 230 feet from the well, was raised nearly 17 centimeters between 2007 and 2011. In the geology world, this is called an uplift, and it usually happens where parts of the earth have been forced upward by underground pressure.

Lu said the most likely explanation for that uplift is that leakage was happening at the nearby well.

“We suspect that the wastewater was accumulated at a very shallow depth, which is quite dramatically different from what the report data says about that well,” he said.

Only one wastewater disposal well is located in close proximity to the uplifted area of the Ken Regan field. The company that owns it reported the injection of 1,040 meters of wastewater deep into the disposal well in Ken Regan. That well is no longer active.

But a combination of satellite images and models done by SMU show that water was likely escaping at a shallower level than the well was drilled for.

And the study, which was published in the Nature publication Scientific Reports, estimates that about 57 percent of the injected wastewater went to this shallower depth. At that shallower depth, the wastewater–which typically contains salt water and chemicals–could have mixed in with groundwater from the nearby Rustler Aquifer. Drinking water doesn’t come from the Rustler Aquifer, which spans seven counties. But the aquifer does eventually flow into the Pecos River, which is a drinking source.

The scientists made the discovery of the leak after analyzing radar satellite images from January 2007 to March 2011. These images were captured by a read-out radar instrument called Phased Array type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR) mounted on the Advanced Land Observing Satellite, which was run by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency

With this technology called interferometric synthetic aperture radar, or InSAR for short, the satellite radar images allow scientists to detect changes that aren’t visible to the naked eye and that might otherwise go undetected. The satellite technology can capture ground deformation with a precision of sub-inches or better, at a spatial resolution of a few yards or better over thousands of miles, say the researchers.

Lu and his team also used data that oil and petroleum companies are required to report to the Railroad Commission of Texas (Texas RRC), as well as sophisticated hydrogeological models that mapped out the distribution and movement of water underground as well as rocks of the Earth’s crust.

“We utilized InSAR to detect the surface uplift and applied poroelastic finite element models to simulate displacement fields. The results indicate that the effective injection depth is much shallower than reported,” Zheng said. “The most reasonable explanation is that the well was experiencing leakage due to casing failures and/or sealing problem(s).”

“One issue is that the steel pipes can degrade as they age and/or wells may be inadequately managed. As a result, wastewater from failed parts can leak out,” said Jin-Woo Kim, research scientist with Lu’s SMU Radar Laboratory and a co-author of this study.

The combination of InSAR imagery and modeling done by SMU gave the scientists a clear picture of how the uplift area in Regan field developed.

Lu, who is world-renowned for leading scientists in using InSAR applications to detect surface changes, said these types of analysis are critical for the future of oil-producing West Texas.

“Our research that exploits remote sensing data and numerical models provides a clue as to understanding the subsurface hydrogeological process responding to the oil and gas activities. This kind of research can further be regarded as an indirect leakage monitoring method to supplement current infrequent leakage detection,” Zheng said.

“It’s very important to sustain the economy of the whole nation. But these operations require some checking to guarantee the operations are environmentally-compliant as well,” Lu said.

Co-author Dr. Syed Tabrez Ali from AIR-Worldwide in Boston also contributed to this study.

This research was sponsored by the NASA Earth Surface and Interior Program and the Schuler-Foscue endowment at SMU.

Previously, Kim and Lu used satellite radar imaging to find that two giant sinkholes near Wink, Texas—two counties over from the Ken Regan uplift—were likely just the tip of the iceberg of ground movement in West Texas. Indeed, they found evidence that large swaths of West Texas oil patch were heaving and sinking at alarming rates. Decades of oil production activities in West Texas appears to have destabilized localities in an area of about 4,000 square miles populated by small towns like Wink, roadways and a vast network of oil and gas pipelines and storage tanks.

Watch the WFAA Verify news segment. You can also hear a report on the study that was broadcast on Austin’s NPR KUT 90.5 below:

About SMU

SMU is the nationally ranked global research university in the dynamic city of Dallas. SMU’s alumni, faculty and nearly 12,000 students in eight degree-granting schools demonstrate an entrepreneurial spirit as they lead change in their professions, communities and the world.