Record-breaking has slowed, but science could find new ways to make us keep getting stronger and faster

Sports writer Matt Porter referenced the research of SMU biomechanics expert Peter Weyand for an article in the news blog The Roar examining the potential for humans to continue improving strength and speed beyond what has already been achieved.

Porter quotes Weyand for his expertise on the mechanics of running and speed of world-class sprinters like Usain Bolt. The article “Humans can’t bolt much faster than Usain: What science says about the 100m world record” published Aug. 15, 2016.

Weyand, director of the SMU Locomotor Performance Laboratory, is one of the world’s leading scholars on the scientific basis of human performance. His research on runners, specifically world-class sprinters, looks at the importance of ground forces for running speed, and has established a contemporary understanding that spans the scientific and athletic communities.

In particular, Weyand’s finding that speed athletes are not able to reposition their legs more rapidly than non-athletes debunked a widespread belief. Rather, Weyand and his colleagues have demonstrated sprinting performance is largely set by the force with which one presses against the ground and how long one applies that force.

Weyand is Glenn Simmons Centennial Chair in Applied Physiology and professor of biomechanics in the Department of Applied Physiology and Wellness in SMU’s Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development.

EXCERPT:

By Matt Porter

The Roar

We’ve just watched the incomparable Usain Bolt ensure his immortality as the greatest sprinter of all time with his third successive 100m Olympic Gold medal in Rio. The world rejoiced and the embattled Rio Olympics organisers and IAAF breathed a sigh of relief as the Great Jamaican ran down twice convicted doping cheat Justin Gatlin to claim his rightful place in the Olympic pantheon.The triumph came barely half an hour after South African Wayde van Niekerk smashed Michael Johnson’s 17-year-old 400m world record to beat home a star-studded field in the final of that event to scorch the lap in 43.03s, a whopping 0.15s faster than the old mark.

What an hour for the fastest humans on the planet. The 100m final is my favourite nine and a bit seconds of any Olympic Games. So primal. So raw. No other modes of transport involved. No distance to endure, water to splash through or bends in the track to negotiate. No racquets, bats, clubs or balls. Just the fastest of a land-based mammal species attempting to out-run one another from start to finish over a very short distance in a straight line.

…Peter Weyand, a biomechanics professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas is a leading expert in human locomotion. He reckons the primary factor influencing speed is how much force sprinters hit the ground with their feet.

When athletes run at a constant speed they use their limbs like pogo sticks, Weyand says. Once a sprinter hits the ground, his limb compresses and gets him ready to rebound. When he’s in the air, the feet get ready to hit the ground again.

Every time a runner hits the ground, 90 per cent of the force goes vertically to push him or her up again, while only 5 per cent propels him or her horizontally. In that regard, sprinters behave a lot like one of those super bouncy balls you play with as a kid, Weyand says. “They bounce a lot.” Our body naturally adjusts to how fast we run by changing how hard we hit the ground. The harder we hit the ground, the faster we go.

So just how hard can humans hit the ground while they run?

Follow SMU Research on Twitter, @smuresearch.

For more SMU research see www.smuresearch.com.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information, www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Geohazard: Giant sinkholes near West Texas oil patch towns are growing — as new ones lurk

Geohazard: Giant sinkholes near West Texas oil patch towns are growing — as new ones lurk Wildfire on warming planet requires adaptive capacity at local, national, int’l scales

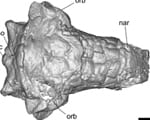

Wildfire on warming planet requires adaptive capacity at local, national, int’l scales Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger

Early armored dino from Texas lacked cousin’s club-tail weapon, but had a nose for danger SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data

SMU physicists: CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is once again smashing protons, taking data Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns

Nearby massive star explosion 30 million years ago equaled brightness of 100 million suns Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple

Text in lost language may reveal god or goddess worshipped by Etruscans at ancient temple Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought

Good news! You’re likely burning more calories than you thought