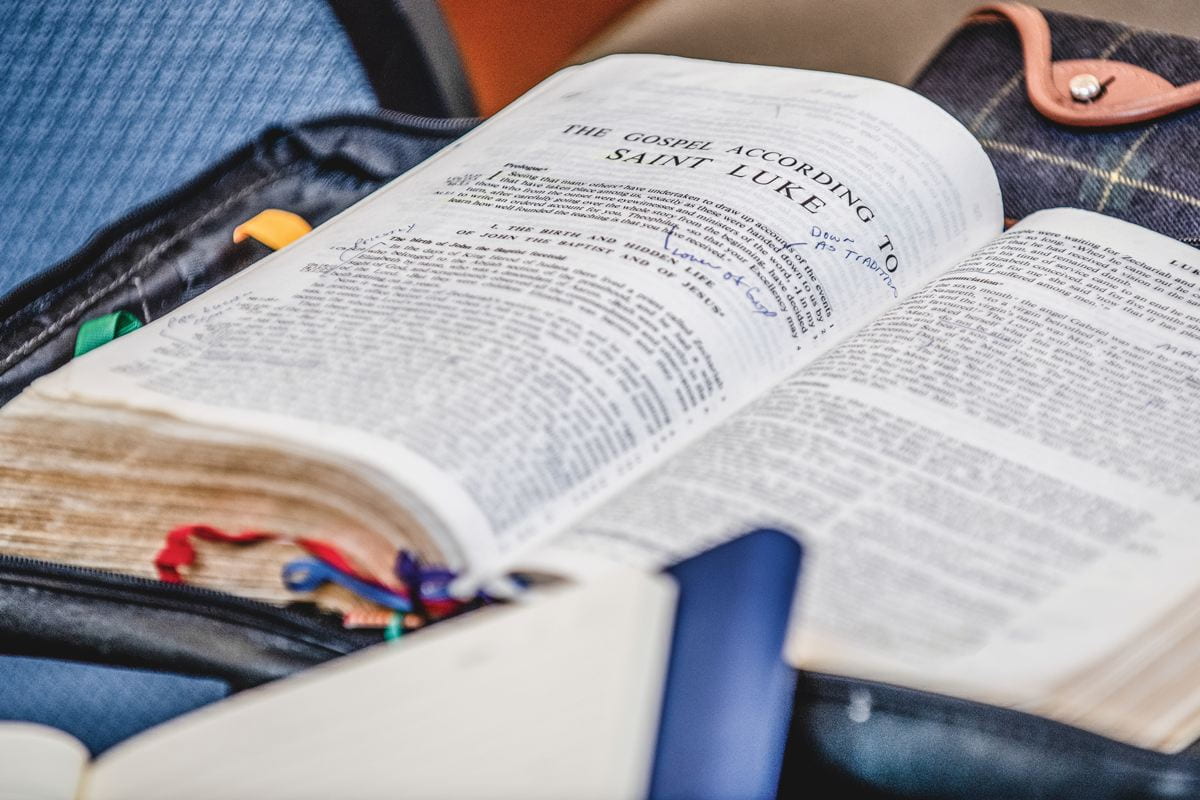

Each of us brings our own story to the reading of the Bible. Perkins students are no different. They come to Perkins from a range of backgrounds, as Bible newbies or longtime students of Scripture. Most evolve in their views of the Bible during their theology studies. We invited several students to reflect on their journeys with the Bible at Perkins; here are their stories.

Sarah Bilaye-Benibo

Sarah Bilaye-Benibo

Master of Sacred Music student

Pentecostal

St. Louis, Missouri

Coming from a very conservative and homogenous background, I knew Perkins would challenge my fundamentalist approach to the Bible. As a worship leader, I was both excited and scared about how much my ministry might change.

Interpretation of the Old Testament with Professor Scholz is probably the most eye-opening class I’ve ever taken. She challenged the class to think critically about the bias we bring to our interpretation of the Bible. I became aware of the dangers of language that reinforce gender bias, hierarchy and antisemitism, including those in worship songs and liturgy. My greatest learning has been that all sacred texts are inherently ambiguous, flexible and “liquid.” The Bible’s interpretation is based on the social location of the reader.

My faith has definitely been challenged, but thankfully I have come to fully embrace the classic definition of theology, attributed to Anselm of Canterbury: “Faith seeking understanding.” My faith drives me to believe that if I continue to seek, I will find. I still believe the Bible is divinely inspired and the best tool we have in understanding the mind of God.

With my education, I hope to help expand the church’s vision of God, to understand that God is not a man, a king or an American. God is a spirit, and, in this way, God is reflected in every living being.

Nick McRae

Nick McRae

Master of Divinity student

Seeking ordination in the United Methodist Church

Richardson, Texas

I have a long, complicated relationship with the Bible. I grew up in a church that takes Scripture very seriously, with an emphasis on refraining from a long list of activities and keeping yourself separate from the world. While I was in college, I became a Quaker and began to question whether the Bible should still be taken super-seriously. By the time I arrived at Perkins, I had these two poles fighting in my brain.

I was really struck by something I learned in Professor Heller’s Old Testament class: the Bible was written by actual people, in actual times, in actual places, for actual circumstances. We need to learn about the context, and the background, to understand what that writer was trying to convey.

I’m a licensed local pastor in a United Methodist church. Teaching Bible study, I often say, “We can trust in God. The Bible is trustworthy. But we must read it with humility. We can’t assume we know ‘the’ way to understand it. Let the Bible grow your faith and your understanding and your love for other people, but always read it with a humble heart, not one that is seeking to be right.” That impulse to be right is often not our friend.

Shandon Klein

Shandon Klein

Master of Divinity student

Seeking ordination in the United Methodist Church

Richardson, Texas

I came to Perkins because I wanted to be at a place where I could hear different interpretations, to learn the Hebrew and Greek and to interpret the texts in the original languages. That has definitely made my experience richer and taught me to appreciate the beauty of the Bible. It’s also been dismaying. When you start to learn about different interpretations, you see how the Bible has been weaponized at times. The classroom helps us out of our ideological bunkers. We get to know one another as brothers and sisters in Christ. That’s an important thing in such times as these.

A big ‘aha’ moment for me was in Professor Heller’s Old Testament class. He explained that the Bible isn’t necessarily a window; it’s more like a mirror. We always bring our own lens, our own experiences, when we read the Bible. We can’t come to the Bible entirely objectively, no matter how hard we try. He also told us not to confuse familiarity with understanding, and that “the only thing that you can’t learn is something you already know.” That’s why the Bible is truly a living word. You can’t assume you know what a passage says, even though you’ve read it a million times. That is what makes the Bible such an amazing work!

Richard Anastasi

Richard Anastasi

Master of Theological student

Roman Catholic

New York, New York

I believe the Bible is the inspired word of God, but I’m not a literalist. Not all parts are meant to be interpreted the same way. Having studied at Perkins, now I can better articulate that.

My Old Testament class with Professor Susanne Scholz exposed me to different hermeneutical lenses, like my own patriarchal, male, Anglo-centric viewpoint. There are other interpretations out there. It’s up for me to decide which I will internalize. In Professor Jaime Clark-Soles’ New Testament class, we viewed a video that compared the poverty and powerlessness of South Africans with the way the Hebrews were treated by Rome. Nothing has changed, and everything has changed. It was very impactful.

Now, when someone says, “Well, the Bible says …” regarding some social, economic or political issue, I ask, “Where? Which translation?” I’ve come to understand that all sacred texts are flexible, elastic and ambiguous. Whether it’s the Bible, the Qu’ran or the Upanishads, a reader creates meaning based on their social context. For example, I read the book of Isaiah four years ago, before coming to Perkins. All I remembered were the gloom and doom prophecies. When I read it again about two years later, all I noticed were the pastoral passages. The words are the same, but I changed.

Lindsay Bruehl

Lindsay Bruehl

Master of Divinity student

Considering ministry in a Baptist church

Dallas, Texas

I was raised in the Church of Christ. The Bible never really interested me, but I loved church. A few years ago, my life fell apart personally and politically, and I started to delve into the Bible. I heard the pain in the Bible of the people who have gone before us, and I fell in love with Scripture.

Some things in the Bible are awful. At Perkins, I learned that it’s meant to make you feel it’s awful. There’s sex trafficking in Bible, for example. No matter what you’ve been through, you can read the Bible and your pain is spoken.

I grew up being told that Jesus was not political, and to stay out of politics. Well, Jesus was political. I think he saw that women were not treated as they should be.

In the church where I grew up, women were not called. But when you look at Mary sitting at Jesus’ feet, that’s a teacher-student posture. She is the one who proclaimed his resurrection. That’s a preacher right there, trained by Jesus. When he met the woman at the well, I think Jesus released her to preach. When I look at Jesus and how he’s operating – he’s freeing women all the time.

Rebecca Chase

Rebecca Chase

Master of Theological student

Pursuing ordination in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Plano, Texas

My background is Lutheran, so I grew up with “sola scriptura,” the idea that the Bible is, for the most part, the inerrant word of God. At Perkins, I became more aware that humans chose what made it into the Bible, and what did not. Yes, they did it prayerfully, but it wasn’t all just God. That was a jarring moment for me, and I’m still struggling a little with that. But I’ve also been empowered to dig into the Bible on my own. Thanks to Professor Sze-Kar Wan’s classes in Greek, and deep dives into Galatians and Romans, I’m more aware of the translation as something I can engage with, rather than just accepting the translation I’m given.

I also learned that we must be aware that we read the Bible in community. Even when we’re reading alone, our interpretations are built from the people we listen to. If we only listen to people with similar perspectives, it’s too easy to come to the kind of “common sense” readings that Americans in the 19th century believed mandated slavery; if we listen uncritically to people we regard as authorities, we can stumble into their traps and create our own. But if we seek voices from different backgrounds, we both gain compassion for the Bible and our sisters and brothers, and help to filter out our own biases.

Macie Liptoi

Macie Liptoi

Master of Divinity student

Seeking ordination in the United Methodist Church

Plano, Texas

To be honest, I wasn’t looking forward to studying the Bible at Perkins. At my conservative Christian undergraduate college, I saw people using the Bible to be oppressive toward others. My first semester at Perkins, Professor Roy Heller’s Old Testament class was the first time someone showed me I could have fun with the Bible. He lectured on the passage where Abraham goes to sacrifice his son Isaac. Growing up, the story meant Abraham was a model of obedience to God. Prof. Heller told us, “No, Abraham failed this test. God never speaks to Abraham again.” That bowled me over. Blind obedience is not faithfulness; reason and our community have to play a role, too.

Professor Jaime Clark-Soles’ New Testament course enlightened me to the complexities of the Gospel of John. It’s not just stories about Jesus; there’s metaphor and interconnection. Nicodemus comes to Jesus at night and leaves in darkness; the Samaritan woman comes at noon and has the first theophany. She’s the first to know who Jesus really is, yet she keeps asking questions. What that taught me is that we are asked to continue in conversation in Christ.

I’m grateful that my Bible professors gave me space to wrestle with all this. It’s been an absolutely transformational experience.