Perhaps because of the unusually bellicose and exceptionally polarized political and cultural environment of 2020, a particular word struck me with force this Christmas season: humility. Nearly every sermon I heard in recent weeks referred to the humble situation of Christ’s birth, as do some favorite Christmas carols, such as “Go, Tell It on the Mountain”:

Down in a lowly manger

Our humble Christ was born

And God sent us salvation

That blessed Christmas morn

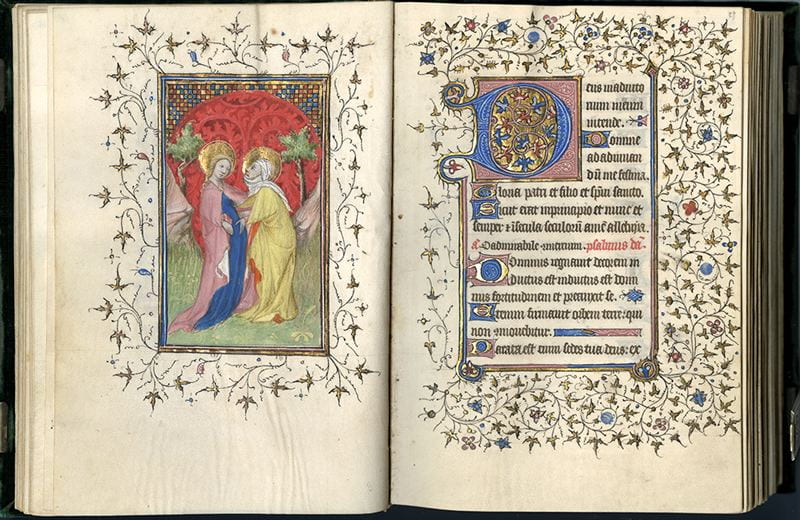

The same theme appears in retellings of the Christmas story in film. In Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth, the “wise men” comment on the surprising situation in which they find Mary, Joseph, and Jesus. Says one, “Now I see the justice of it,” to which another nods and replies, “Not in glory, but in humility.” This is in keeping with Mary’s canticle of praise, the Magnificat, in Luke 1, in which she extols God, who “has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant.” It also aligns with a great many characterizations of Jesus in the New Testament, such as the Christ Hymn in Philippians 2, in which Jesus was said to have “humbled himself.” Indeed, in Matthew 11:28, Jesus says of himself, “I am gentle and humble in heart”.

So, what does it do to our understanding of humility if Jesus is the standard? Humility is often associated with states such as passivity, weakness, guilt, self-deprecation, and a lack of conviction. But Jesus evidenced none of these things. He acted deliberately, exhibited extraordinary strength of character, and possessed obvious conviction. Recall, for example, the people’s response to him in Matthew 7:29: “Now when Jesus had finished saying these things, the crowds were astounded at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as their scribes.” How, then, might we describe the humility of Jesus?

First, it came from strength, not weakness. Unlike his opponents and even his own disciples, Jesus possessed a secure identity, which is a powerful source of freedom. For one thing, it is freedom from enslavement to the opinions of others. This in turn made Jesus free to serve. He spent his ministry associating with the very people—tax collectors, lepers, the poor, and Samaritans among them—who could do nothing to advance him, all the while alienating those who could. Moreover, his secure identity gave him the power to do what he believed to be right, irrespective of the opinions of others and even irrespective of the consequences to himself. The author of Hebrews put it this way: “Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the sake of the joy that was set before him endured the cross, disregarding its shame” (12:2).

As demonstrated by Jesus, humility is not egocentric. It has no need to be. Instead, it is outwardly directed, focused on others. All of us know what it is like to love in such a way that, at least momentarily, we forget about ourselves, our own priorities and ego needs. Those are among the most joy-filled moments of our lives, times when, according to the apostle Paul, we “have the mind of Christ” (Philippians 2:3-5):

Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility reckon others as though better than yourselves. Let each of you look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others. Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus…

Much the same conception was famously characterized by the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber as a relationship between “I and Thou,” that is, between myself and another individual whom I recognize as being a person of value. This is opposed to an “I and it” relationship, which is essentially transactional. Others are treated as objects I manipulate to achieve my own purposes. For the truly humble, the self is not on the line, so it is free to recognize the significance and needs of others. This also means that it is able to have an honest and realistic view both of itself and of others. Humility is not false modesty, pretending, for example, not to possess the gifts it obviously does. Instead, it recognizes that they are gifts, that others possess gifts of equal value, and that any such gifts are given for the benefit of all. In one sense, humility is nothing more than simple honesty. It is realistic about itself and therefore also about others.

Contrast all of this with the state of non-humility, which is evidence of fundamental weakness and an insecure identity—ironically, often manifesting itself as arrogance, boastfulness, and conceit. This self is fragile, under constant threat, and therefore anxious. Because of the need to justify itself, it has great difficulty seeing either itself or anyone else realistically. It is in bondage to the opinions of others, whom it must use as objects to affirm and advance itself. The need to prop itself up makes self-forgetful and joyous service difficult if not impossible. Similarly, the need to be seen and affirmed elevates expedience far above moral conviction. Indeed, morality becomes a disposable expedient, sometimes useful to the self, but often not.

Jesus himself repeatedly warned that the practice of religion was subject to these very pitfalls. This is memorably expressed in a series of verses in Matthew 6:

“Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them; for then you have no reward from your Father in heaven. So whenever you give alms, do not sound a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, so that they may be praised by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward.”

“And whenever you pray, do not be like the hypocrites; for they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, so that they may be seen by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward.”

“And whenever you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces so as to show others that they are fasting. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward.” (Verses 1-2, 5, 16)

A number of other examples could be cited, but perhaps the best single statement is found in Matthew 23:5-7: “They do all their deeds to be seen by others…They love to have the place of honor at banquets and the best seats in the synagogues, and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces…” Notably, these words were addressed to religious leaders, and they are just as challenging to us today who are clergy. Chances are, we entered ministry in part because others recognized and praised certain qualities in us. That is not wrong. Indeed, it is likely necessary. But there is a persistent danger that we, like those whom Jesus challenged, will come to define ourselves by that praise and so will use religion as a seemingly-sanctified means to an ultimately hypocritical end. I imagine all religious leaders are guilty of that to some extent, myself included.

Of course, parallel temptations exist in nearly every profession. A few years ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education ran a series of articles decrying the mean-spirited culture of many universities (not SMU, by the way!). University faculties are largely composed of people who grew up being told how intelligent they are, and who thus came to hold themselves to the standard of being right at least, say, 97.5% of the time. Imagine a community of dozens or even hundreds of such well-educated individuals, some significant percentage of whom have constructed a self-imagine that requires them to be seen as the smartest person in the room. The wonder is not that one-upmanship, professional jealousy, and backstabbing occur among faculty, but that the problem is not worse than it actually is.

Jesus’ own disciples fell into this trap, jostling with each other for position in the expectation that they would participate in their master’s glory once he established his reign in Jerusalem. Similarly, a great many of the problems experienced in Paul’s congregations were not doctrinal in nature but had at their heart this same dynamic. This is seen most dramatically in the apostle’s correspondence with the church of Corinth, whose members were masters of self-glorification, whether, for example, by claiming allegiance to the superior apostle or by possession of a superior spiritual endowment. Paul responds plainly and forcefully:

[N]one of you should be puffed up in favor of one against another. For who sees anything different in you? What do you have that you did not receive? And if you received it, why do you boast as if it were not a gift? (1 Corinthians 4:6-7)

The New Testament’s perspective on humility is to varying extents paralleled in other religious and philosophical texts. More recently, it is also echoed in books on psychology and even business leadership. (Think of the “Level-Five Leader” in the well-known Jim Collins book Good to Great, whose distinctive characteristic is humility.) Just last week, I came across an article in Scientific American titled The Pressing Need for Everyone to Quiet Their Egos: Why quieting the ego strengthens your best self. The author, Scott Barry Kaufman, asserts that “A noisy ego spends so much time defending the self as if it were a real thing, and then doing whatever it takes to assert itself, that it often inhibits the very goals it is most striving for.” In other words, our human need to justify ourselves keeps us from being the very people we might most want to be and might most enjoy being.

A nearly identical point is made in the Arbinger Institute’s two popular books Leadership and Self-Deception and The Anatomy of Peace. Both books locate human strife (not to mention business inefficiency!) explicitly in the need for self-justification. Whenever we fail to do something we know intuitively we ought to have done, we place ourself “in the box,” where we are self-justifying, amplifying our own virtue and innocence, and unfairly undermining and even demonizing others.

While I have great appreciation for these (and very many similar) analyses, the problem would seem to require both a fuller explanation and solution. We are social animals—indeed, by far and away the most sophisticated of social animals, possessing the ultimate social adaptation, language. As I have written elsewhere[1], the need to be “somebody” is in our DNA. A major part of our brain is constantly at work, most often subconsciously, to position us socially. Put another way, we are wired to be meaning-seeking creatures. To use biblical language, we need to be justified.

Jesus’ response to the disciples is revealing:

Then they came to Capernaum; and when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But they were silent, for on the way they had argued with one another who was the greatest. He sat down, called the twelve, and said to them, “Whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all.” (Mark 9:33-35)

Note what Jesus did not say: “You fools! Don’t you realize you have no significance, that you are nothing?” Instead, he challenged their view of both the source and the nature of true significance. As Paul put it in Romans 8:33, “It is God who justifies.” Indeed, in any ultimate sense, it is only God who can justify.

And herein lies the paradox. To the extent that we find ourselves in God, to know in God that we are wholly loved, we are able to let go of the need to establish some other self with some other center of significance. The paradigm is, again, Jesus. I often refer to the foot-washing story in John 13 because it so beautifully captures this reality and so completely challenges us by its example. Jesus was the only one in the room who knew who he was, and thus the only one free to serve.

God came to us in a manger. That is a profound lesson of Christmas whose meaning we can work to realize throughout the new year. To the extent we do, we will be empowered to serve freely, to act justly, and to live in joy and at peace—that is, to experience the true power of humility. Most of us are aware how difficult this can be, how tempting it is to fall back on long-established, hard-won patterns of self-justification. So, let us find hope in the words of the angel Gabriel to Mary nine months prior to that first Christmas: “For with God, nothing shall be impossible” (Luke 1:37).

[1] See Chapter Two, “It’s Only Natural,” in Servant of All: Status, Ambition, and the Way of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016).