By Mary Jacobs

You wouldn’t expect Susanne Scholz and William J. “Billy” Abraham to be good friends. You might

even wonder whether the two Perkins faculty members could manage a civil conversation.

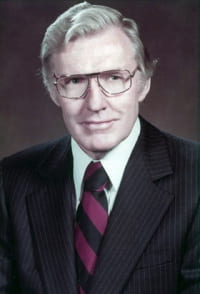

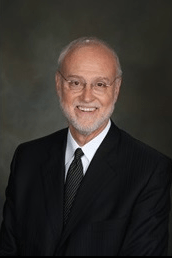

Scholz is a professor of Old Testament, a feminist who’s currently teaching a course in Queer Bible Hermeneutics. Abraham, who is Albert Cook Outler Professor of Wesley Studies, defends his theologically conservative understanding of the Christian faith. On many issues, the two Perkins faculty members couldn’t be further apart. Yet their friendship, which began in 2013, has endured.

Here are excerpts from a lively and wide-ranging 90-minute conversation with Scholz and Abraham on what makes the friendship work.

Tell me how you became friends.

Abraham: It started in a faculty meeting. I was on my usual soapbox about intellectual and theological diversity at Perkins, and I said, “Maybe somebody like me should teach a course with Susanne Scholz.” There were gasps around the room. Jaws dropped. But you got in touch with me and we met over tea. I found it very challenging. I think you were worried about giving a platform to this stodgy, doctrinaire, dogmatic, orthodox Christian.

Scholz: Worse! I had been warned. (Laughs.) I was warned that you would turn around every statement I’m making into something else, and I wouldn’t recognize it anymore. I didn’t like that idea.

Abraham: It took a while for us to get beyond the stereotypes.

What got you past the stereotypes? You ended up team-teaching a course in the fall of 2015 on Postmodern Biblical Historiography.

Scholz: I think we are both very European, in that we believe in this intellectual endeavor within this anti-intellectual culture. American culture has no patience for intellectual debate. It basically says, ‘Let’s just stop talking and do it; let’s get it done.’ Billy and I are very abstract conceptual thinkers. That’s our strength, and we appreciate each other on that level.

Abraham: I’ve always had a significant curiosity about people who disagree with me. I wanted to get clarity on the alternative vision that Susanne’s work and her intellectual illuminations involve to harvest the best insights for my point of view. Some of it was just chemistry. This is where friendship comes in. To be able to meet over a glass of wine and rhubarb pie.

Scholz: With a little ice cream, yes.

Abraham: That is important. It’s not just confined to our work. People at Perkins care for one another, across these divisions. I’ve called Susanne about family issues. A few years ago, when the University issued a directive from on high that I found troubling, Susanne was the first person I called, to test my instincts.

Your story invites comparisons with the friendship between Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the late Antonin Scalia — two Supreme Court justices famously at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Do you see any parallels?

Scholz: You can call me Ruth.

Abraham: I do like Scalia’s philosophy of law. Regarding the Constitution, he was an originalist.

Scholz: When you listen to the confirmation hearings of the Supreme Court justices — which I did, as much as I could, because I found them so fascinating — you realize that they were making hermeneutical arguments. The things Billy and I disagree and debate over are not just theological issues.

Abraham: I am originalist in reading the Scripture; I care about the author’s intent.

Scholz: This is where our deep differences surface. I actually say in my classes, “The Bible is the word of God. But what do I mean by that?” The Bible is metaphorical language; it’s not historical language. I’m not talking history as we understand history at Dedman College. As an academic, we have a shared vocabulary and shared assumptions, and they are not to say that the Bible is historical fact.

Abraham: I think this is the heart of theology. I think we can talk perfectly legitimately about God doing things: raising Jesus from the dead, becoming incarnate, speaking to the prophets, sending me to Texas for my sins. The assumption that God doesn’t poke his nose into history or do anything beyond what happens naturally or through human action — I think that’s a highly dubious assumption to make theologically.

You are each from parts of the world where conflicts over ideas had life-and-death consequences. Is that part of the equation here?

Scholz: Yes. I was raised in post-Holocaust Germany.

Abraham: And I’m from Northern Ireland.

Scholz: I think it’s fruitful and essential to have interaction across the aisle. I couldn’t even fathom thinking along the same lines as Billy does, and yet there it is. There’s a human who’s thinking in a very different way. I think we need this kind of interaction. That’s the value of a democratic system.

Abraham: We also share a broadly liberal arts conception of theology, that theology should be part of the University; it shouldn’t just be confined to a school of theology on the edge

of the campus or seen as a kind of upgrade of a Sunday school. We both think theology is a very important discipline. The reality and character of God really matter. These issues have social and political implications, and we both want to have an accurate account of them.

Scholz: We also share a kind of irreverence and a willingness to challenge the orthodoxies in our respective areas. We’re each willing to go with what we’ve concluded is the position to be defended, even if it’s going to incite people left and right. I thought that was very German. But apparently, it’s Northern Irish, too.

One of the most divisive issues in the United Methodist church right now is human sexuality. This is a key area where you disagree, yes?

Scholz: Yes. With all the joviality, we’ve sort of bracketed that subject. I think we should be for justice. For reasons I can’t fathom, Billy is set in his position. To me, it’s a nonissue.

Abraham: It’s not a nonissue, because you consider my position to be morally offensive and homophobic, and damaging to people. That’s a big issue.

Scholz: I know.

Abraham: And I don’t want you to back off that.

Scholz: I’m not backing off.

Let’s talk about what you have in common.

Scholz: Here’s what I think we agree on: democracy, free speech and thought, pedagogy and taking theology seriously.

Abraham: We are both really serious scholars. We’re not happy to simply get tenure and then take it easy. We also both love gossip — figuring out what’s going on in the higher echelons of the University.

Scholz: We both have a sense of humor. We love to argue. We love to hear good arguments. We like to challenge, and we like to investigate, ponder, reflect and analyze, so we both love our work. I mean, I think he’s always wrong and he thinks I’m always wrong on the content. But the form matters too, right?

Abraham: We have very different views, but, at the end of the day, we are prepared to step out and say what we’ve received may need to be revised or rejected. We both have a love of scholarship and a very strong sense of respect for each other’s scholarship. There’s a very deep respect here — that what we’re about is radically different, but it’s worth doing, and it’s worth doing well.

Is there something about Perkins that fosters this kind of friendship?

Abraham: Yes. I think our ability to get together is

part of our DNA at Perkins, which goes back to the complementary work of Schubert Ogden and the late John Deschner, faculty members at Perkins for many years beginning in the mid-1950s. I think they helped create Perkins as a place that was prepared to say, “Look, we’re going to have differences, and we’re going to lock the doors and work those through. I disagree with him from top to bottom, but I consider Schubert Ogden to be one of the finest liberal theologists of the 20th century. Deschner studied with Karl Barth; he managed to get Barth to take John Wesley seriously. To me, those two were a symbol of what Perkins was about. To be able to be part of this community with that kind of intellectual horsepower, it’s fantastic.

Scholz: At the academic level, theology is staking out your territory, testing the waters with your thinking

and your arguments. I think we agree on that. I’m glad that there’s space for me and some other progressively inclined theologians here. But I think Perkins could be stronger in the progressive realm of theological studies. Perkins may seem very liberal because we are living in a state that’s still fairly conservative. But in other circles, we’re viewed as moderate.

Abraham: I think it would be a tragedy if Perkins became identified as a school that primarily stoops for a progressive agenda.

Scholz: That’s not what I’m saying. I’m saying, in terms of the progressive academic discourse, we are tame as a group.

We live in divisive times. Is there something your story can offer the rest of the world?

Abraham: When one works as a scholar, you work hard at a problem. You live in that silo. You don’t really know the fullness of your own issue until someday someone steps up and says, “I don’t even want to put the issue that way. I have a completely alternative way of thinking through what’s at stake.” So, there’s a sense in which self-knowledge depends upon the kind of conversation across the aisle that we are talking about.

Scholz: I think our story teaches us to keep talking.

I think Perkins could do an even better job of communicating our diversity and maybe fostering more actively this kind of across-the-aisle conversation. It could be our cutting edge. The millennials want this kind of conversation.

“We both have a sense of humor. We love to argue. We love to hear good arguments. We like to challenge, and we like to investigate, ponder, reflect and analyze, so we both love our work.”

SUSANNE SCHOLZ