By Sam Hodges

When future histories of Perkins School of Theology are written, they will need a chapter at least on the current period, with its daunting challenges.

For weeks, the Perkins campus, with the rest of Southern Methodist University, has been closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All classes have gone online – an unprecedented undertaking. Commencement was postponed until August, with no date certain for the campus reopening.

Meanwhile, economists forecast a major recession for the U.S. owing to so many shut down or reduced businesses. If the recession comes, it will do so as The United Methodist Church faces the likelihood of a breakup and sharply reduced spending – including aid to Perkins and other United Methodist seminaries.

The clouds are mounting, but solace might be taken from the already published histories of Perkins. They show the school has faced and overcome challenges from its inception.

Indeed, Perkins School of Theology: A Centennial History, written by emeritus professor Joseph L. Allen, has a chapter titled “Years of Struggle.” A sub-chapter carries the headline “Crisis after Crisis.”

The School of Theology opened with Southern Methodist University in 1915, a joyous occasion for those who strived to add a major Methodist college and pastor-training school west of the Mississippi River.

But in less than three years, the U.S. had entered World War I.

“The effects of the war on student work in Southern Methodist University are felt perhaps more keenly by the Theological Department than by any other,” reported The Campus, the SMU student newspaper, on Oct. 1, 1918. “Last year there were more than eighty ministerial candidates. This year the number is reduced to some twenty.”

The fall of 1918 also brought the Spanish flu pandemic, claiming some SMU students’ lives and forcing quarantines not unlike those of today. One early School of Theology graduate and beginning pastor, Frank Rye, was a double victim of major events of 1918. He entered the U.S. Army chaplaincy only to die of influenza on November 29 that year.

Two years after the peak of Spanish flu, Frank Seay, an original School of Theology faculty member, beloved on campus and beyond, died of influenza at age 38. His death and funeral were covered in lengthy articles in the Dallas Morning News.

All through its early years, financial insecurity plagued SMU and with it the School of Theology. Debts mounted yearly. A visiting committee of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, called the situation “little short of desperate.” Judge Joseph Cockrell, SMU board chair, was even more plain when interviewing Hiram Boaz for the school’s presidency.

“I don’t believe you, or any other man, can save the University,” Cockrell said as reported in Allen’s history. “It is gone, hook and line. But I want to see you try it.”

Boaz would become SMU’s second president and prove to be the saving fundraiser. But during his tenure John Rice, an Old Testament professor, came under attack in the Texas Christian Advocate and elsewhere for his book The Old Testament in the Life of Today. Worn down by accusations of heresy and receiving less than firm support from Boaz and Cockrell, Rice resigned in 1921, causing unrest in the School of Theology and tarnishing SMU’s reputation for protecting academic freedom.

The 1930s saw SMU and the School of Theology struggling financially once more, due to the Great Depression. Faculty salaries had been sharply reduced by 1932 and took years to recover.

Times were tough for students too.

“A lot of students, the only way they could go was to carry a church and maybe several churches, and then to have another job,” Allen said by phone.

Bishop John Wesley Hardt, who died in 2017 at age 95, shared in interviews and his own writings just how resourceful ministerial students such as himself had to be. While still studying theology at SMU in 1941, Hardt led five small churches in Bowie County, Texas. Unable to afford a car, the future bishop-in-residence at Perkins rode buses and sometimes hitchhiked to get to them.

World War II would cause a drop in male enrollment at SMU as well as the arrival of a Navy V-12 training program, including chaplaincy training for some theology students. In 1946, memorial services were held on campus for 131 former SMU students killed in the war. The address was given by Umphrey Lee, school president and an early theology student. Robert Goodloe, a professor in the School of Theology, gave the concluding prayer.

On Feb. 6, 1945, near the end of the war, the announcement came that Joe and Lois Craddock Perkins of Wichita Falls, Texas, were giving $1.5 million to the School of Theology. One Hundred Years on the Hilltop, Darwin Payne’s centennial history of SMU, says the gift was both the largest SMU had received and the largest given to any theology school in the U.S. It would prompt the renaming of the school for the Perkins and the creation of the present campus, including Bridwell Library and the Mark Lemmon-designed Perkins Chapel.

But the school’s challenges did not end. After World War II, as enrollment swelled with returning veterans supported by the GI bill, SMU created a trailer village near campus and employed used barracks at White Rock Lake for student housing.

The Rev. Wallace Shook, 93, recalls that when he entered Perkins as an Army Air Corps veteran in 1947, all he and his wife could find was a trailer between Dallas and Fort Worth. They shared a bath with the families in the trailers nearby. Better, closer housing would come soon, but Shook, like Hardt, had to balance schoolwork with serving small rural churches.

He at least had a car to travel to his four-point charge in and around Laneville, Texas.

“It was a 1940 Chevrolet, and the (gear) shift was on the steering wheel,” he said.

The 1950s saw Perkins rise in academic standing under Dean Merrimon Cuninggim and star faculty members he recruited. Perkins also was a pioneer for SMU in integration, admitting five African American students in 1952. They would graduate on time, three years later, but not without behind-the-scenes drama over Cuninggim’s insistence that they be allowed to live in the dorms and room with white students.

Social change would accelerate in the 1960s, with Perkins’ increasing number of women students pushing to be taken more seriously, and black students asserting their own concerns. The school would soon hire its first female and African American professors and create a Mexican American Program.

Challenges have continued right along, including the 2007-2009 Great Recession, which cost the seminary positions through attrition, recalled former Dean William Lawrence.

A seminary education requires students to confront the hardships faced by Job and so many other Biblical characters, and to derive theology from them and their stories. It is perhaps fitting that Perkins’ story has its share of tribulation.

In an oral history interview, the late Perkins professor Bill McElvaney described his experience as a student at the school in the 1950s, enthusing about one professor after another.

But he also recalled how Professor Joe Mathews would often tell students, without explanation, “If you’ve never been to Waxahachie, you’ve never been to Waxahachie – but you will.”

Only gradually, McElvaney said, did he and the others realize “Waxahachie” was a Mathews’ code word.

It meant hard times.

Sam Hodges is a Dallas-based freelance writer and editor for United Methodist News Service.

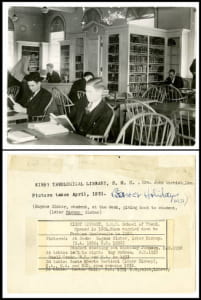

Photos courtesy of Joan Gosnell, SMU University Archivist.