Andrew Klumpp is a Ph.D. Student in American religious history in the Graduate Department of Religious Studies at Southern Methodist University.

The American Academy of Religion’s annual meeting is a somewhat unique conference experience for historians. One of the most exciting elements about attending AAR, which took place in Boston this year, is the interdisciplinarity that’s there. In my conference-going professional life, I rarely hobnob with Jewish ethicists, biblical exegetes, or anthropologists interested in Taiwanese Buddhism. I get to do that at AAR. Chatting with such diverse folks can be both fruitful and at times, a challenge.

I am a U.S. historian interested in religion. I work in archives, study the past, and employ historical methods in my work. And, there’s a place for me at AAR. In fact, there is a cadre of historians running around the conference, if you know where to look—people ranging from enthusiastic grad students like me to established figures like Laurel Thatcher Ulrich.

As I write this blog sitting on a return flight somewhere over the square states where I grew up, two sessions in particular continue to linger.

One of the thorniest issues in American religious history these days has got to be grappling with the definition of the term “evangelical.” I showed up to a paper session on evangelicalism to see how religious studies scholars grappled with these definitions. I left disappointed. Two of the five papers used the term somewhat precisely; the other three tended to collapse evangelicalism broadly construed, white evangelicalism, and conservative evangelicalism into one category. In light of work like David Swartz The Moral Minority and scholarship on black and Asian evangelicals, I longed for more clarity. I also wondered if struggles with defining evangelicalism might be particularly acute among historians since we so clearly see that the evangelicalism of George Whitefield or Sarah Osborn was radically different than the evangelicalism of Franklin Graham and Paula White.

Before catching my plane to Dallas, I ducked into one final panel. I’m so glad I did! The Mormon Studies Unit hosted an author-meets-critic session about Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s most recent book A House Full of Females—one of the finest books I’ve read in the past six months. Ulrich received widespread praise from the panelists as well as engaging queries. Her kindness, graciousness, and insight provided a master class for how to engage in charitable and generative historical dialogue. In summing up some final thoughts, Ulrich reminded those of us in attendance of her abiding belief that what we do day by day really matters, and that if we believe that the everyday holds significance and power, it should show up how we interpret the past. These wise words from one of my favorite historians were certainly worth a slightly hurried trip to the airport.

This year’s conference also marked the first time that I presented my own work at a discipline-wide national conference. While the audience was larger than previous presentations I’ve given at smaller conferences, the geniality of the group and its response provided a great opportunity to hone my scholarship and gain invaluable feedback. My panel focused on how beliefs influenced civic engagement among Christians. Of the four papers on my panel, mine was decidedly the most historical, drawing on archival research and full of the travails of rural immigrants building new communities in the American Midwest in the nineteenth century.

I received valuable feedback on some of these initial thoughts for my dissertation, yet one of the most valuable lessons I learned from the process involved owning my space and identity as a historian. A few of the other panelists employed more theological or anthropological methods, but I stuck to my historical approach and was able to articulate how my work as a historian contributed to conversations even among those who utilized other approaches. I am thoroughly convinced historians have valuable contributions to make to interdisciplinary work, and I’m grateful not only for the chance to present my work but also for the continued opportunity represent historians and historical methods in these conversations.

Of course, in addition to excellent sessions, the conference also offered fruitful opportunities for networking and mentorship. Evening receptions led to engaging conversations with old friends and new colleagues. AAR also provided multiple graduate student mentoring opportunities. A luncheon connected small groups of graduate students with faculty mentors who answered questions about the job market, the challenges of graduate school, and career diversity. I also took advantage of AAR’s one-on-one mentoring program. This led to a rich conversation with an established professor and American religious historian who also happens to be a first-generation college student. Over a cup of coffee, we chatted about pedagogy, historical scholarship, graduate school, and our experiences as the first in our families to attend college.

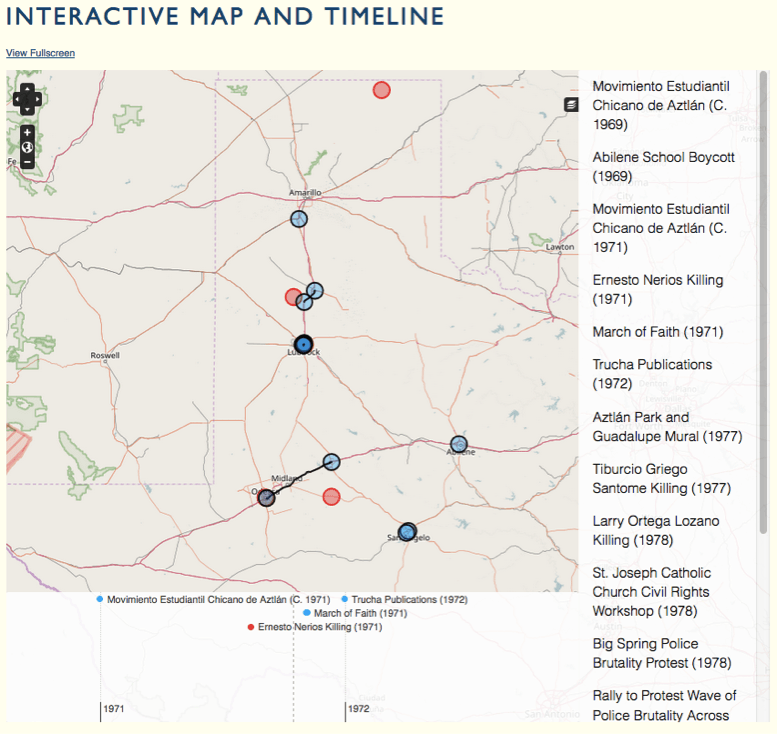

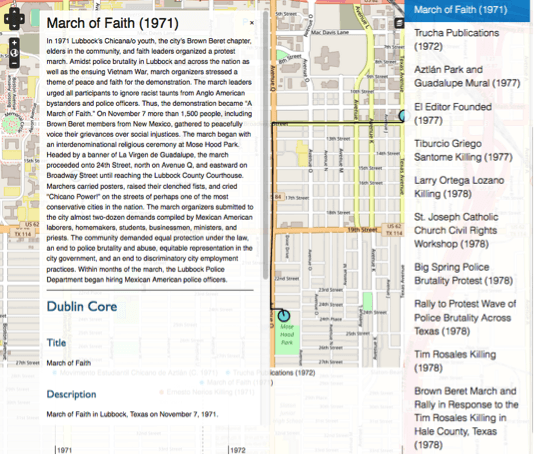

After two days of rain, on a brisk 32-degree Monday morning, I ventured into Boston. I made my way to Boston Common, past many of the old meeting houses, and several other quintessential Boston landmarks. For the past semester, I was a teaching assistant for Kate Carté Engel’s Doing Digital History: Mapping the Great Awakening course. With our students, we’ve mapped sites throughout much of Boston. As an added conference bonus, I got to look at some of this landmarks with new eyes, thinking spatially about the history that surrounded me.

As my flight begins its final descent into Dallas, a number of questions continue to linger after this most recent conference. I continue to nurture my voice as a historian in interdisciplinary conversations and am grateful for both the intellectual stimulation and sage advice I discovered in Boston this weekend. What is more, the whole experience makes me even more eager for AHA in January when I get to do it all over again.

on a roundtable about the legacy of revolutions in the Atlantic world. Cynthia Bouton kicked off the discussion with her exploratory paper on the role of subsistence in the Caribbean during the era of revolutions. Looking at Haiti particularly, she questioned the role French colonies played in the French Revolutionary program based on the food commitments France made to the island. Building on Michel-Rolph Trouillot, she posited that peripheries drove the centers since they demanded constant attention and maintenance. Manuel Covo, in his paper, asked similar questions about the relationship between Haiti and France, but in the context of the historiography of each nation’s revolution. Noticing that Haiti rarely appears in the French national narrative, he made a call for more global histories, especially regarding the age of revolutions. Also with a nod to Trouillot, Covo claimed that national histories and historiographies too often obscure important trends, themes, and arguments made on the global stage. Caitlin Fitz shifted the discussion to the United States and its role in this period. She provided insights into how Americans viewed the Latin American revolutions, specifically the abolitionist trend that went with them. She concluded that the seeming U.S. support for Latin America’s revolutions was quite shallow as Americans tended to focus on how those revolutions related to the American Revolution. Since Latin America’s push for abolition did not seem to threaten American slavery in the eyes of Southern slave holders, it was easy to support their movements until the Panama Conference drove Latin American abolition to the U.S. political stage. Finally, Lester Langley provided his thesis that the entire Western Hemisphere needs to be studied and taught as a coherent unit. The discussion after the papers proved quite lively as the presenters debated the role the American Revolution played to initiate change while also maintaining slavery as a cornerstone institution in the United States.

on a roundtable about the legacy of revolutions in the Atlantic world. Cynthia Bouton kicked off the discussion with her exploratory paper on the role of subsistence in the Caribbean during the era of revolutions. Looking at Haiti particularly, she questioned the role French colonies played in the French Revolutionary program based on the food commitments France made to the island. Building on Michel-Rolph Trouillot, she posited that peripheries drove the centers since they demanded constant attention and maintenance. Manuel Covo, in his paper, asked similar questions about the relationship between Haiti and France, but in the context of the historiography of each nation’s revolution. Noticing that Haiti rarely appears in the French national narrative, he made a call for more global histories, especially regarding the age of revolutions. Also with a nod to Trouillot, Covo claimed that national histories and historiographies too often obscure important trends, themes, and arguments made on the global stage. Caitlin Fitz shifted the discussion to the United States and its role in this period. She provided insights into how Americans viewed the Latin American revolutions, specifically the abolitionist trend that went with them. She concluded that the seeming U.S. support for Latin America’s revolutions was quite shallow as Americans tended to focus on how those revolutions related to the American Revolution. Since Latin America’s push for abolition did not seem to threaten American slavery in the eyes of Southern slave holders, it was easy to support their movements until the Panama Conference drove Latin American abolition to the U.S. political stage. Finally, Lester Langley provided his thesis that the entire Western Hemisphere needs to be studied and taught as a coherent unit. The discussion after the papers proved quite lively as the presenters debated the role the American Revolution played to initiate change while also maintaining slavery as a cornerstone institution in the United States.

Slavery.” All the papers added significantly to the discussion of that contentious field. Ian Beamish showed that, in fact, planters kept terrible accounting records, meaning they likely did not contribute specifically to modern corporate accounting as the historiography previously hypothesized. Justene Hill presented her research that suggests that ideas of efficiency and paternalism combined in the discourse of the slave economy which fed into the proslavery arguments of the mutual dependence of slaves and slaveowners and slavery as a positive good. John Lindbeck, in the last paper of the panel, connected evangelicalism to the ideas of slavery and capitalism. He argued that planters ran efficient evangelical finance networks to create “God’s proslavery kingdom.” The kinship and finance networks planters built in the church tied faith and family to the business of slavery. Afterward, the discussion revealed the divide among historians about the validity of the study of capitalism and slavery. While the panelists fielded questions about the definitions of capitalism and paternalism, the debate spilled out into the crowd as individuals provided their own commentary to the questions asked. The fireworks that concluded the panel provided insights into how historians work out contentiousness in their field.

Slavery.” All the papers added significantly to the discussion of that contentious field. Ian Beamish showed that, in fact, planters kept terrible accounting records, meaning they likely did not contribute specifically to modern corporate accounting as the historiography previously hypothesized. Justene Hill presented her research that suggests that ideas of efficiency and paternalism combined in the discourse of the slave economy which fed into the proslavery arguments of the mutual dependence of slaves and slaveowners and slavery as a positive good. John Lindbeck, in the last paper of the panel, connected evangelicalism to the ideas of slavery and capitalism. He argued that planters ran efficient evangelical finance networks to create “God’s proslavery kingdom.” The kinship and finance networks planters built in the church tied faith and family to the business of slavery. Afterward, the discussion revealed the divide among historians about the validity of the study of capitalism and slavery. While the panelists fielded questions about the definitions of capitalism and paternalism, the debate spilled out into the crowd as individuals provided their own commentary to the questions asked. The fireworks that concluded the panel provided insights into how historians work out contentiousness in their field.

Throughout the book, Guardino builds a sustained and compelling case against a myth that has long haunted interpretations of the Mexican-American War in both countries. This myth suggests that Mexico lost the war primarily because it lacked the stability and national unity of its northern neighbor. Guardino, on the other hand, shows that the war’s outcome had far more to do with the economic and social disparities between the two countries. An assortment of geographical, political, and social forces combined to give the U.S. a strong material advantage. At the same time, costly mobilization efforts, a violent U.S. occupation, and the U.S. Navy’s blockade of Mexican ports compounded Mexico’s already dire economic situation and aggravated its internal conflicts. The loss of revenue from import duties crippled the financially strapped Mexican state, while the war’s demands further burdened a society already living on an economic knife-edge. Given this harsh reality, Guardino shows that the fierce and sustained resistance that Mexicans made against the U.S. invasion was nothing short of remarkable. Working to overcome deep internal divisions and constantly weighing the stark realities of personal and family survival, Mexicans from all walks of life contributed to and participated in the war effort. In doing so, they unequivocally declared and demonstrated their Mexican nationalism. “In short,” Guardino concludes, “Mexico lost the war because it was poor, not because it was not a nation” (367).

Throughout the book, Guardino builds a sustained and compelling case against a myth that has long haunted interpretations of the Mexican-American War in both countries. This myth suggests that Mexico lost the war primarily because it lacked the stability and national unity of its northern neighbor. Guardino, on the other hand, shows that the war’s outcome had far more to do with the economic and social disparities between the two countries. An assortment of geographical, political, and social forces combined to give the U.S. a strong material advantage. At the same time, costly mobilization efforts, a violent U.S. occupation, and the U.S. Navy’s blockade of Mexican ports compounded Mexico’s already dire economic situation and aggravated its internal conflicts. The loss of revenue from import duties crippled the financially strapped Mexican state, while the war’s demands further burdened a society already living on an economic knife-edge. Given this harsh reality, Guardino shows that the fierce and sustained resistance that Mexicans made against the U.S. invasion was nothing short of remarkable. Working to overcome deep internal divisions and constantly weighing the stark realities of personal and family survival, Mexicans from all walks of life contributed to and participated in the war effort. In doing so, they unequivocally declared and demonstrated their Mexican nationalism. “In short,” Guardino concludes, “Mexico lost the war because it was poor, not because it was not a nation” (367).