By: Camille Davis

Photo Courtesy of clipart.com

As the world reels from the news regarding the sudden and horrendous death of 41-year-old Kobe Bryant and his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, it seems as though no particular tribute or testimony provides the adequate amount of answers or comfort. Grief is often debilitating, and when it is met with shock, the two culminate into a potion — or sometimes a poison — that seems impenetrable.

Although this is the case, we at The Future of the Past believe that historians have a mandate to tackle life as it comes — or in the case of history — has come. History is filled with both triumph and disaster, as well as questions that have no easy, definitive explanations. Ours is a field that encompasses the entirety of the human experience, and it is a field that provides a long, broad lens from which to examine both past and current events. With this in mind, we join the rest of the world in submitting our “ad perpetuam rei memoriam,” our “permanent record of the matter” regarding the loss of one of the most well-known and respected cultural icons of the 20th and 21st centuries.

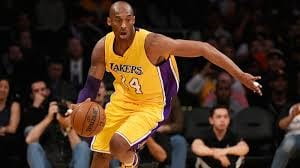

Exceptionalism

Bryant’s professional, athletic accomplishments are well-documented. Among them are being a first -round NBA pick during the 1996 draft, earning 5 NBA championships and two Olympic gold medals, appearing in 18 All-Star games, setting an NBA record as the third-highest scoring player in a single game until Lebron James surpassed his record on January 25th, and playing with the Los Angeles Lakers for twenty-years, which is more than three times the span of the average, professional athlete’s career. Yet interestingly, despite the gravitas of his NBA record, Bryant’s life off the court seems to provide the most compelling components of his legacy.

Mamba Mentality

“Mamba Mentality” is a term that Bryant famously coined in 2016. He described it as the ability to “be the best version of yourself.” He named himself “Black Mamba” after a snake that was used as the symbol of an assassin in Quentin Tarantino’s 2003 film “Kill Bill.” The term evolved into a mantra about challenging oneself for greatness, exceeding the boundaries of physical and mental comfort, rising to the occasion, and focusing on solutions instead of excuses. In 2018, Bryant formally articulated this philosophy by co-writing a book called The Mamba Mentality: How I Play. The book became a manifesto for goal setters — both athletes and non-athletes — about how to meet the challenges of life with courage and commitment. New Orleans Saints All-Pro linebacker Demario Davis told USA Today, “Kobe’s impact transcends the game of basketball. It transcends life… Mambo mentality is more of an approach than anything else. It’s about attacking what’s in front of you with passion and purpose, without fear and doubt and without an ounce of quit.”

Bryant used this ethos to guide his post-pro-basketball life with the same intensity and intent that guided his time on the court. And equally as important, he spent his time in retirement encouraging others to do the same.

In 2016, he began the Mambo Sports Academy with the specific goal of mentoring athletes at every level of the game: NBA players, potential NBA recruits, high school students, and children. The academy included men, women, boys, and girls, and it was symptomatic of the teaching, support, and encouragement that Kobe had generously given to younger athletes during a large portion of his career. During the summer of 2019, Kobe Bryant and his Mambo Sports Academy hosted NBA players Kawhi Leonard, Paul George, Kyrie Irving, Jamal Murray, De’Aaron Fox, Tobias Harris, Isaiah Thomas, and Kentavious Caldwell-Pope.

ESPN’s Ramona Shelburne recently explained that as Bryant planned to leave the NBA, she conceptualized writing an article about him that would “top them all.” When pitching her story idea to Bryant, she admits to appealing to his ego in order to get his permission to write a story that would be filled with grandiose language. She inferred that her article would simultaneously flatter Kobe while advancing her own career. Bryant saw right through Shelburne and declined. Instead of accepting a piece filled with vainglory, he encouraged her to write something authentic.

“He said he’d do a story with me about his life, but not out of vanity — mine or his,” she admitted. He told her, “I’m not interested in self-serving pieces. It has to be something where an athlete reads it and is inspired by something, learns something, and pushes themselves.”

Bryant’s famed “Dear Basketball” retirement poem confirmed this reality. He was done with vanity. He was ready to see himself — and for the world to see him—as he truly was: strong yet vulnerable to the wears and tears that time and experience unequivocally make upon the body.

The Beauty of Authenticity

In 2018, at the 90th Academy Awards, Bryant earned an Oscar within the category of “Best Animated Short Film” after turning his retirement poem into an animated film. He chose storied, Disney animator, Glen Keane, as his illustrator for the film, and he tapped legendary composer John Williams to write the film’s score. Though not formally educated past high school, Bryant was a known intellectual who favored Beethoven, which impacted the rhythm and tone of the music he preferred to accompany his autobiographical poetry.

Mumba Mentality and “Dear Basketball” were not the only pieces of literature Bryant penned. In early 2019, he began publishing the first volume of a children’s book series called The Wizenards, through his media company Granity Studios. Bryant co-wrote the series with author Wesley King. The next editions of the series were supposed to launch in March of this year. King has stated that the news of Kobe’s and his daughter, Gianna’s, deaths led him to delete the manuscript. The first edition of the series made The New York Times best seller list.

In addition to writing formally, Bryant also regularly made time to send text to friends and colleagues whom he believed needed encouragement. ESPN writers Ramona Shelburne and Jackie MacMullan both wrote pieces this week attesting to Bryant’s generosity of spirit exhibited through his notes of inspiration.

Fatherhood

The person he encouraged and instructed most passionately was his 13 year-old-daughter, Gianna, who was one of four daughters he shared with his wife, Vanessa. In addition to his usual fatherly activities, he spent a significant amount of his time mentoring Gianna in basketball and providing tutorials to her AAU teammates when they visited the Mambo Sports Academy. Both Gianna’s death and her fathers were premature, and there will never be a human explanation insightful enough to ease the torment of their passing.

Final Analysis

Despite the tragedy of this moment, it is reasonable to assume that Bryant lived the end of his life with a peace about himself and all that he accomplished. His epic achievements and adventures are astonishing and inspiring for those who witnessed them or subsequently learned of them, but they seem right in line with what young, Kobe Bryant planned and fantasized about as a boy growing up in California and in Italy. As he scurried around shooting tube socks pretending to make clutch plays, as he describes in “Dear Basketball,” one can imagine a notebook, a journal, or maybe even a scrap of paper with a detailed plan for his life and these Italian words scribbled across the top of the page: Perpetuam Rei Memoriam, The Final Records of the Matter, before those records ever even occurred.

On behalf of your fans at SMU, rest well Kobe and Gianna.

on a roundtable about the legacy of revolutions in the Atlantic world. Cynthia Bouton kicked off the discussion with her exploratory paper on the role of subsistence in the Caribbean during the era of revolutions. Looking at Haiti particularly, she questioned the role French colonies played in the French Revolutionary program based on the food commitments France made to the island. Building on Michel-Rolph Trouillot, she posited that peripheries drove the centers since they demanded constant attention and maintenance. Manuel Covo, in his paper, asked similar questions about the relationship between Haiti and France, but in the context of the historiography of each nation’s revolution. Noticing that Haiti rarely appears in the French national narrative, he made a call for more global histories, especially regarding the age of revolutions. Also with a nod to Trouillot, Covo claimed that national histories and historiographies too often obscure important trends, themes, and arguments made on the global stage. Caitlin Fitz shifted the discussion to the United States and its role in this period. She provided insights into how Americans viewed the Latin American revolutions, specifically the abolitionist trend that went with them. She concluded that the seeming U.S. support for Latin America’s revolutions was quite shallow as Americans tended to focus on how those revolutions related to the American Revolution. Since Latin America’s push for abolition did not seem to threaten American slavery in the eyes of Southern slave holders, it was easy to support their movements until the Panama Conference drove Latin American abolition to the U.S. political stage. Finally, Lester Langley provided his thesis that the entire Western Hemisphere needs to be studied and taught as a coherent unit. The discussion after the papers proved quite lively as the presenters debated the role the American Revolution played to initiate change while also maintaining slavery as a cornerstone institution in the United States.

on a roundtable about the legacy of revolutions in the Atlantic world. Cynthia Bouton kicked off the discussion with her exploratory paper on the role of subsistence in the Caribbean during the era of revolutions. Looking at Haiti particularly, she questioned the role French colonies played in the French Revolutionary program based on the food commitments France made to the island. Building on Michel-Rolph Trouillot, she posited that peripheries drove the centers since they demanded constant attention and maintenance. Manuel Covo, in his paper, asked similar questions about the relationship between Haiti and France, but in the context of the historiography of each nation’s revolution. Noticing that Haiti rarely appears in the French national narrative, he made a call for more global histories, especially regarding the age of revolutions. Also with a nod to Trouillot, Covo claimed that national histories and historiographies too often obscure important trends, themes, and arguments made on the global stage. Caitlin Fitz shifted the discussion to the United States and its role in this period. She provided insights into how Americans viewed the Latin American revolutions, specifically the abolitionist trend that went with them. She concluded that the seeming U.S. support for Latin America’s revolutions was quite shallow as Americans tended to focus on how those revolutions related to the American Revolution. Since Latin America’s push for abolition did not seem to threaten American slavery in the eyes of Southern slave holders, it was easy to support their movements until the Panama Conference drove Latin American abolition to the U.S. political stage. Finally, Lester Langley provided his thesis that the entire Western Hemisphere needs to be studied and taught as a coherent unit. The discussion after the papers proved quite lively as the presenters debated the role the American Revolution played to initiate change while also maintaining slavery as a cornerstone institution in the United States.

Slavery.” All the papers added significantly to the discussion of that contentious field. Ian Beamish showed that, in fact, planters kept terrible accounting records, meaning they likely did not contribute specifically to modern corporate accounting as the historiography previously hypothesized. Justene Hill presented her research that suggests that ideas of efficiency and paternalism combined in the discourse of the slave economy which fed into the proslavery arguments of the mutual dependence of slaves and slaveowners and slavery as a positive good. John Lindbeck, in the last paper of the panel, connected evangelicalism to the ideas of slavery and capitalism. He argued that planters ran efficient evangelical finance networks to create “God’s proslavery kingdom.” The kinship and finance networks planters built in the church tied faith and family to the business of slavery. Afterward, the discussion revealed the divide among historians about the validity of the study of capitalism and slavery. While the panelists fielded questions about the definitions of capitalism and paternalism, the debate spilled out into the crowd as individuals provided their own commentary to the questions asked. The fireworks that concluded the panel provided insights into how historians work out contentiousness in their field.

Slavery.” All the papers added significantly to the discussion of that contentious field. Ian Beamish showed that, in fact, planters kept terrible accounting records, meaning they likely did not contribute specifically to modern corporate accounting as the historiography previously hypothesized. Justene Hill presented her research that suggests that ideas of efficiency and paternalism combined in the discourse of the slave economy which fed into the proslavery arguments of the mutual dependence of slaves and slaveowners and slavery as a positive good. John Lindbeck, in the last paper of the panel, connected evangelicalism to the ideas of slavery and capitalism. He argued that planters ran efficient evangelical finance networks to create “God’s proslavery kingdom.” The kinship and finance networks planters built in the church tied faith and family to the business of slavery. Afterward, the discussion revealed the divide among historians about the validity of the study of capitalism and slavery. While the panelists fielded questions about the definitions of capitalism and paternalism, the debate spilled out into the crowd as individuals provided their own commentary to the questions asked. The fireworks that concluded the panel provided insights into how historians work out contentiousness in their field.