Dean Craig C. Hill’s Servant of All: Status, Ambition, and the Way of Jesus (Eerdmans, 2016) has found a readership among United Methodist church leaders, church members more generally, and in the secular world. Hill talked to Sam Hodges about the book and about nurturing servanthood at Perkins.

What made you want to write about servanthood, ambition, and the Christian life?

Both personal and professional reasons. I’ve been reading the Bible most of my life and therefore was aware of Jesus’ admonitions about humility and servanthood. I also had a career, first in ministry and then in the academy. So, personally, I wanted to explore what this means in terms of: Do I apply for jobs? Do I seek promotions? Do I try to advance? How as a Christian do I think faithfully about such matters?

Professionally, I’ve taught in doctor of ministry programs, including directing the one at Duke Divinity School. The more I worked with mid-career pastors, the more I realized that servanthood, ambition and the Christian life presented a pressing issue for many of them. A number had reached career plateaus and were frustrated, even disillusioned. After being in ministry a while, they saw who got attention, who got promoted and who got the more desirable church appointments. So it was easy for their early vocational mindset to shift imperceptibly into a careerist mindset.

If you do that, you’re likely to be disappointed because the opportunities for “advancement” in ministry are increasingly slim. Even if you succeed, you’re going to be egocentric — your thoughts and efforts will be focused on yourself. Everyone I’ve known who is chronically unhappy has one thing in common: they are scorekeepers. They are keenly aware of who is getting what, and whether they’re being slighted. We have to remember that service isn’t fair. (Of course, neither is grace.) It’s not about advancement, at least not in the way we usually imagine it.

As a New Testament scholar, these things jumped off the page at me. If the standard is what Jesus gave us, which is that the greatest is the servant of all, then how are we to live? That became of increasing interest to me over the years.

Another piece of this is my lifelong interest in science. So, for me, one of the default questions is: Why are we the way we are? Why do we care what anybody thinks of us? There’s a simple answer: It’s because we are social animals. It is deeply embedded in our DNA to concern ourselves — consciously but even more unconsciously — with where we fit in the group. The fact that we have ambition and that we think about how others perceive us isn’t abnormal. But, as with any other natural impulse, we need to discern how to deal with it faithfully.

How should we deal with ambition, in light of the New Testament?

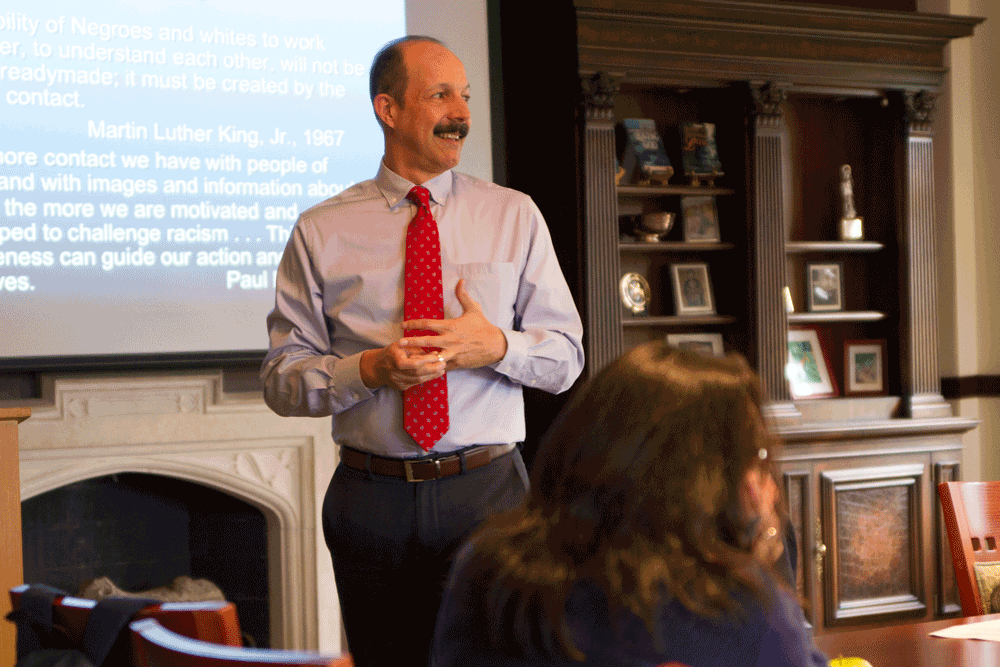

When Paul says in Romans 12:10, “outdo one another in showing honor,” he is offering a perspective in line with that of Jesus but radically opposed to that of the wider culture. What one sought to do in the Roman world was outdo others in receiving honor. The person who outdid everyone in showing honor was a slave. Life was seen as a continual competition for honor. One of the goals of Servant of All is to show just how countercultural the teaching of the New Testament on this subject actually is. That is why I quote a number of Greco-Roman authors, such as Cicero, Seneca and Dio Chrysostom. Human nature being what it is, these writers sound remarkably contemporary.

The core story of the book is that of the foot-washing in John 13. In the ancient world, persons who washed someone else’s feet acknowledged by that act their own low status. Understandably, the disciples, who were continually jockeying for position, did not want to do this. Jesus flips the normal order: the leader takes the place of the servant, but in so doing, continues all the more to lead.

That’s an essential lesson for us — to believe enough in God, to believe enough in our own justification by God’s grace, that our identity is so fundamentally established that, like Jesus, we can be free to serve without our service being dependent on public reward. We should ask ourselves, “What would we still do if no one could give us credit for doing it?” If you find that strong purpose, you’ve found your true ministry.

“We should ask ourselves, ‘What would we still do if no one could give us credit for doing it?’ If you find that strong purpose, you’ve found your true ministry.”

DEAN HILL

We love to look to heroes, including in the Christian faith. Where ought we to look for Christian heroes, the true servant leaders?

Among others, I think of a priest I know who has a phenomenal ministry. He’s not particularly attractive in conventional ways, but he is so given over to his mission that you can’t help but be drawn to him. There’s a deep authenticity about him. His care for his mission and for the people whom he serves allows him to be remarkably unselfconscious, even self-forgetful. That’s the kind of leader we need, one who is invested in something more important than themselves. Such a person is a light in the darkness.

What is the role of community in helping Christians live into servanthood?

As Christians we want to create communities where the things God honors are honored. A key New Testament story for me is that of the widow’s mite. Here is a woman who was invisible to everyone; she wasn’t significant in the world’s eyes, but it was she whom Jesus singled out and honored. He saw her. In the economy of God, she was the greatest. That story should haunt us all, especially those of us in positions of visibility.

You can tell a lot about a church by how it distributes its attention. Are people valued according to the standards of the wider society, or is that order somehow challenged, even inverted, so that people who aren’t good looking, who don’t have impressive job titles or make a lot of money, are recognized as being significant and encouraged to have real ministries? To the extent that happens, we model what the New Testament authors themselves labored to produce in their own communities.

How are you stressing servanthood in the Perkins community?

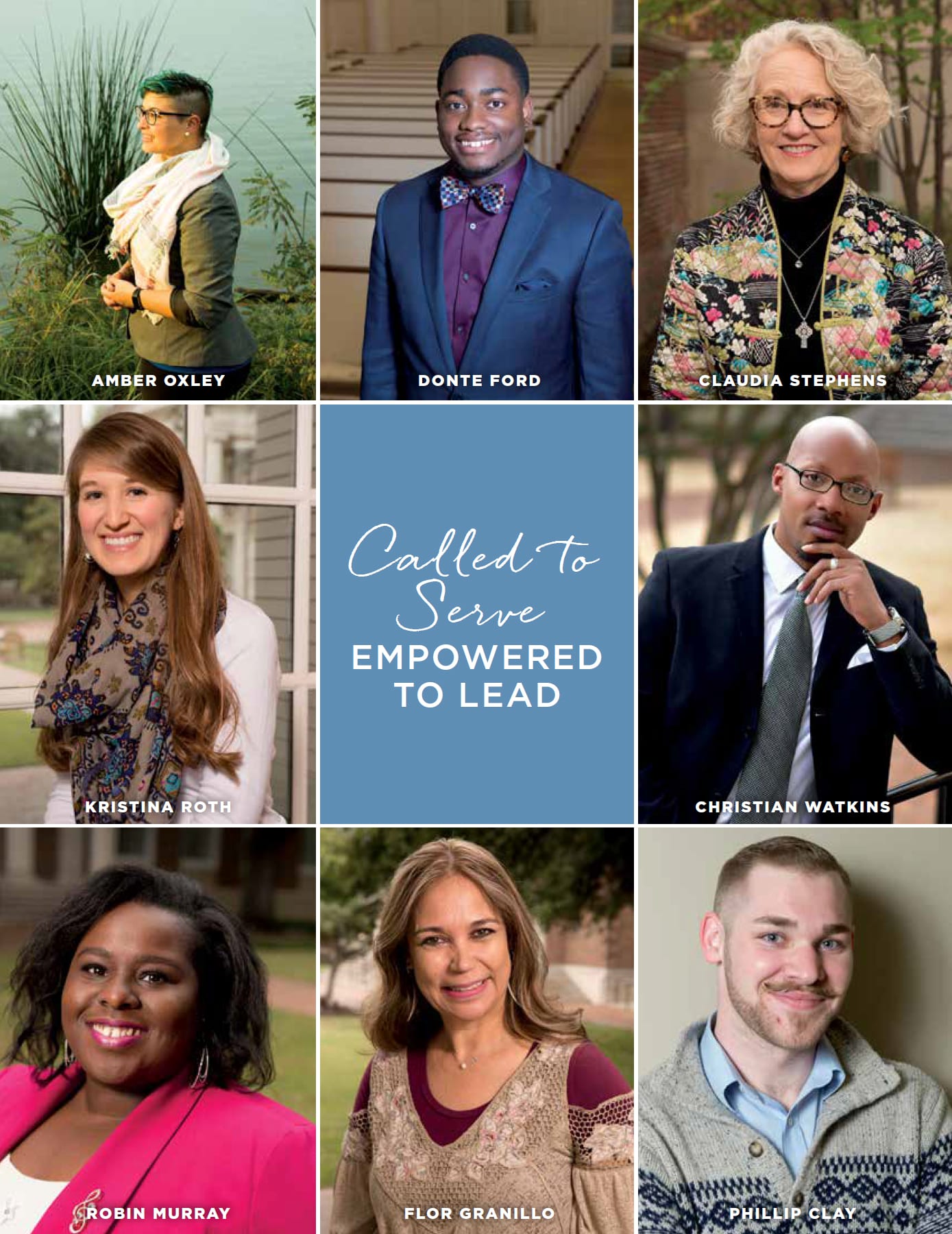

The on-campus seminary community is composed of three main groups: faculty, staff and students. It is not unusual for staff in such institutions to feel undervalued, like cogs in the machine. The faculty are the stars. What would it look like if the staff were seen as being equally valued partners in the mission of the school, as having ministries of their own? There will be students for whom an assistant in the library or some other staff member turns out to be the most important person in their seminary experience.

So, we’ve been doing things like creating a staff council, trying to give staff more opportunities, including a more formal voice in the school, and more intentionally caring for them.

More broadly, we have been working to create community across these groups, so that we all get to know each other better, so that we see each other first as people and not as positions. When you do that, you enable a different kind of conversation.

One of my great hopes for Perkins — and it’s a hope already realized, to a large extent, before I came — is that it be one of the rare places where people with substantial disagreements can actually be together in community, learn from one another, even love one another. The bar Jesus set wasn’t that we were required to tolerate each other but that we were required to love each other, even our (real or, more often, imagined) “enemies.”

Do you see a servanthood element to any of the initiatives you’ve undertaken, such as having Perkins students take courses with professors from the Cox School of Business and Meadows School of the Arts?

It’s out of service to the church that we listen to the church and ask, “What are things we could do that would be more useful, more helpful?” Most of the initiatives we’re undertaking, and still more that are under discussion, come directly out of conversations with church leaders.

Also, we’re looking not just to send students to other parts of the University but to have students from other parts of the University come here. I think this is a vital part of the future of Perkins — we’ll have more and more students who are earning a degree at Simmons [School of Education] or Meadows or Cox, who are people of faith and who say, “I’d like to integrate my faith into my educational or my arts or my business career.” We want to provide opportunities for those students to do that.

In this and other ways, we are seeking to serve the wider University. The environment within SMU right now is very conducive to this kind of shared purpose and shared work, which I find exciting. One of the very best things about Perkins is in fact SMU and all the opportunities that exist here for our students.

You wrote Servant of All while a professor at Duke, and before it was even published, you became dean of Perkins. Then you added a preface acknowledging the irony of an author of a book about servanthood taking a seminary’s top job.

There are a few places in the book where I make reference to deans specifically – one in comparison to gorillas! I didn’t want to excise those from the book, so I thought it was necessary to write a little preface to say these weren’t actually meant to be self-referential!

But, yes, I had to wrestle with my motives, as anyone would as a Christian when something like that comes along. You have to ask yourself: How much of this is calling and the desire to serve, and how much of this is ego and the desire to be seen? I suppose in a move like this, one’s motives are never likely to be absolutely pure, but you need to test them and try your best to be brutally honest with yourself and with God. Of course, it helps if you can laugh at yourself, especially at your foolish pretentions.

I am grateful for the chance to do this work, but I will in time hand the baton on to another, and the memory of what I have done here will rapidly fade. When a new pope is installed, the master of ceremonies repeats three times the phrase sic transit gloria mundi: “the glory of this world passes away.” It is good for us all to remember that fact and so not take ourselves too seriously. It is for and in God that what we do has lasting value.

— As told to Sam Hodges