SMU scientists and their research have a global reach that is frequently noted, beyond peer publications and media mentions.

By Margaret Allen

SMU News & Communications

It was a good year for SMU faculty and student research efforts. Here is a small sampling of public and published acknowledgements during 2015:

Hot topic merits open access

Taylor & Francis, publisher of the online journal Environmental Education Research, lifted its subscription-only requirement to meet demand for an article on how climate change is taught to middle-schoolers in California.

Co-author of the research was Diego Román, assistant professor in the Department of Teaching and Learning, Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development.

Román’s research revealed that California textbooks are teaching sixth graders that climate change is a controversial debate stemming from differing opinions, rather than a scientific conclusion based on rigorous scientific evidence.

The article, “Textbooks of doubt: Using systemic functional analysis to explore the framing of climate change in middle-school science textbooks,” published in September. The finding generated such strong interest that Taylor & Francis opened access to the article.

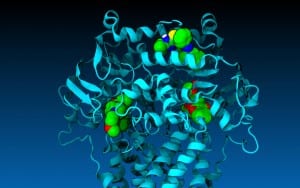

Research makes the cover of Biochemistry

Drugs important in the battle against cancer were tested in a virtual lab by SMU biology professors to see how they would behave in the human cell.

A computer-generated composite image of the simulation made the Dec. 15 cover of the journal Biochemistry.

Scientific articles about discoveries from the simulation were also published in the peer review journals Biochemistry and in Pharmacology Research & Perspectives.

The researchers tested the drugs by simulating their interaction in a computer-generated model of one of the cell’s key molecular pumps — the protein P-glycoprotein, or P-gp. Outcomes of interest were then tested in the Wise-Vogel wet lab.

The ongoing research is the work of biochemists John Wise, associate professor, and Pia Vogel, professor and director of the SMU Center for Drug Discovery, Design and Delivery in Dedman College. Assisting them were a team of SMU graduate and undergraduate students.

The researchers developed the model to overcome the problem of relying on traditional static images for the structure of P-gp. The simulation makes it possible for researchers to dock nearly any drug in the protein and see how it behaves, then test those of interest in an actual lab.

To date, the researchers have run millions of compounds through the pump and have discovered some that are promising for development into pharmaceutical drugs to battle cancer.

Click here to read more about the research.

Strong interest in research on sexual victimization

Teen girls were less likely to report being sexually victimized after learning to assertively resist unwanted sexual overtures and after practicing resistance in a realistic virtual environment, according to three professors from the SMU Department of Psychology.

The finding was reported in Behavior Therapy. The article was one of the psychology journal’s most heavily shared and mentioned articles across social media, blogs and news outlets during 2015, the publisher announced.

The study was the work of Dedman College faculty Lorelei Simpson Rowe, associate professor and Psychology Department graduate program co-director; Ernest Jouriles, professor; and Renee McDonald, SMU associate dean for research and academic affairs.

The journal’s publisher, Elsevier, temporarily has lifted its subscription requirement on the article, “Reducing Sexual Victimization Among Adolescent Girls: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial of My Voice, My Choice,” and has opened it to free access for three months.

Click here to read more about the research.

Consumers assume bigger price equals better quality

Even when competing firms can credibly disclose the positive attributes of their products to buyers, they may not do so.

Instead, they find it more lucrative to “signal” quality through the prices they charge, typically working on the assumption that shoppers think a high price indicates high quality. The resulting high prices hurt buyers, and may create a case for mandatory disclosure of quality through public policy.

That was a finding of the research of Dedman College’s Santanu Roy, professor, Department of Economics. Roy’s article about the research was published in February in one of the blue-ribbon journals, and the oldest, in the field, The Economic Journal.

Published by the U.K.’s Royal Economic Society, The Economic Journal is one of the founding journals of modern economics. The journal issued a media briefing about the paper, “Competition, Disclosure and Signaling,” typically reserved for academic papers of broad public interest.

Chemistry research group edits special issue

Chemistry professors Dieter Cremer and Elfi Kraka, who lead SMU’s Computational and Theoretical Chemistry Group, were guest editors of a special issue of the prestigious Journal of Physical Chemistry. The issue published in March.

The Computational and Theoretical research group, called CATCO for short, is a union of computational and theoretical chemistry scientists at SMU. Their focus is research in computational chemistry, educating and training graduate and undergraduate students, disseminating and explaining results of their research to the broader public, and programming computers for the calculation of molecules and molecular aggregates.

The special issue of Physical Chemistry included 40 contributions from participants of a four-day conference in Dallas in March 2014 that was hosted by CATCO. The 25th Austin Symposium drew 108 participants from 22 different countries who, combined, presented eight plenary talks, 60 lectures and about 40 posters.

CATCO presented its research with contributions from Cremer and Kraka, as well as Marek Freindorf, research assistant professor; Wenli Zou, visiting professor; Robert Kalescky, post-doctoral fellow; and graduate students Alan Humason, Thomas Sexton, Dani Setlawan and Vytor Oliveira.

There have been more than 75 graduate students and research associates working in the CATCO group, which originally was formed at the University of Cologne, Germany, before moving to SMU in 2009.

Vertebrate paleontology recognized with proclamation

Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings proclaimed Oct. 11-17, 2015 Vertebrate Paleontology week in Dallas on behalf of the Dallas City Council.

The proclamation honored the 75th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, which was jointly hosted by SMU’s Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences in Dedman College and the Perot Museum of Science and Nature. The conference drew to Dallas some 1,200 scientists from around the world.

Making research presentations or presenting research posters were: faculty members Bonnie Jacobs, Louis Jacobs, Michael Polcyn, Neil Tabor and Dale Winkler; adjunct research assistant professor Alisa Winkler; research staff member Kurt Ferguson; post-doctoral researchers T. Scott Myers and Lauren Michael; and graduate students Matthew Clemens, John Graf, Gary Johnson and Kate Andrzejewski.

The host committee co-chairs were Anthony Fiorillo, adjunct research professor; and Louis Jacobs, professor. Committee members included Polcyn; Christopher Strganac, graduate student; Diana Vineyard, research associate; and research professor Dale Winkler.

KERA radio reporter Kat Chow filed a report from the conference, explaining to listeners the science of vertebrate paleontology, which exposes the past, present and future of life on earth by studying fossils of animals that had backbones.

SMU earthquake scientists rock scientific journal

Findings by the SMU earthquake team reverberated across the nation with publication of their scientific article in the prestigious British interdisciplinary journal Nature, ranked as one of the world’s most cited scientific journals.

The article reported that the SMU-led seismology team found that high volumes of wastewater injection combined with saltwater extraction from natural gas wells is the most likely cause of unusually frequent earthquakes occurring in the Dallas-Fort Worth area near the small community of Azle.

The research was the work of Dedman College faculty Matthew Hornbach, associate professor of geophysics; Heather DeShon, associate professor of geophysics; Brian Stump, SMU Albritton Chair in Earth Sciences; Chris Hayward, research staff and director geophysics research program; and Beatrice Magnani, associate professor of geophysics.

The article, “Causal factors for seismicity near Azle, Texas,” published online in late April. Already the article has been downloaded nearly 6,000 times, and heavily shared on both social and conventional media. The article has achieved a ranking of 270, which puts it in the 99th percentile of 144,972 tracked articles of a similar age in all journals, and 98th percentile of 626 tracked articles of a similar age in Nature.

“It has a very high impact factor for an article of its age,” said Robert Gregory, professor and chair, SMU Earth Sciences Department.

The scientific article also was entered into the record for public hearings both at the Texas Railroad Commission and the Texas House Subcommittee on Seismic Activity.

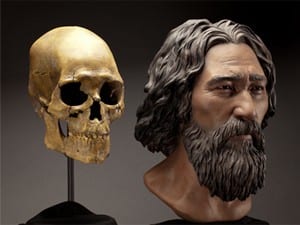

Researchers settle long-debated heritage question of “The Ancient One”

The research of Dedman College anthropologist and Henderson-Morrison Professor of Prehistory David Meltzer played a role in settling the long-debated and highly controversial heritage of “Kennewick Man.”

Also known as “The Ancient One,” the 8,400-year-old male skeleton discovered in Washington state has been the subject of debate for nearly two decades. Argument over his ancestry has gained him notoriety in high-profile newspaper and magazine articles, as well as making him the subject of intense scholarly study.

Officially the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Kennewick Man was discovered in 1996 and radiocarbon dated to 8500 years ago.

Because of his cranial shape and size he was declared not Native American but instead ‘Caucasoid,’ implying a very different population had once been in the Americas, one that was unrelated to contemporary Native Americans.

But Native Americans long have claimed Kennewick Man as theirs and had asked for repatriation of his remains for burial according to their customs.

Meltzer, collaborating with his geneticist colleague Eske Willerslev and his team at the Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen, in June reported the results of their analysis of the DNA of Kennewick in the prestigious British journal Nature in the scientific paper “The ancestry and affiliations of Kennewick Man.”

The results were announced at a news conference, settling the question based on first-ever DNA evidence: Kennewick Man is Native American.

The announcement garnered national and international media attention, and propelled a new push to return the skeleton to a coalition of Columbia Basin tribes. Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) introduced the Bring the Ancient One Home Act of 2015 and Washington Gov. Jay Inslee has offered state assistance for returning the remains to Native Tribes.

Science named the Kennewick work one of its nine runners-up in the highly esteemed magazine’s annual “Breakthrough of the Year” competition.

The research article has been viewed more than 60,000 times. It has achieved a ranking of 665, which puts it in the 99th percentile of 169,466 tracked articles of a similar age in all journals, and in the 94th percentile of 958 tracked articles of a similar age in Nature.

In “Kennewick Man: coming to closure,” an article in the December issue of Antiquity, a journal of Cambridge University Press, Meltzer noted that the DNA merely confirmed what the tribes had known all along: “We are him, he is us,” said one tribal spokesman. Meltzer concludes: “We presented the DNA evidence. The tribal members gave it meaning.”

Click here to read more about the research.

Prehistoric vacuum cleaner captures singular award

Science writer Laura Geggel with Live Science named a new species of extinct marine mammal identified by two SMU paleontologists among “The 10 Strangest Animal Discoveries of 2015.”

The new species, dubbed a prehistoric hoover by London’s Daily Mail online news site, was identified by SMU paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs, a professor in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences, and paleontologist and SMU adjunct research professor Anthony Fiorillo, vice president of research and collections and chief curator at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science.

Jacobs and Fiorillo co-authored a study about the identification of new fossils from the oddball creature Desmostylia, discovered in the same waters where the popular “Deadliest Catch” TV show is filmed. The hippo-like creature ate like a vacuum cleaner and is a new genus and species of the only order of marine mammals ever to go extinct — surviving a mere 23 million years.

Desmostylians, every single species combined, lived in an interval between 33 million and 10 million years ago. Their strange columnar teeth and odd style of eating don’t occur in any other animal, Jacobs said.

SMU campus hosted the world’s premier physicists

The SMU Department of Physics hosted the “23rd International Workshop on Deep Inelastic Scattering and Related Subjects” from April 27-May 1, 2015. Deep Inelastic Scattering is the process of probing the quantum particles that make up our universe.

The SMU Department of Physics hosted the “23rd International Workshop on Deep Inelastic Scattering and Related Subjects” from April 27-May 1, 2015. Deep Inelastic Scattering is the process of probing the quantum particles that make up our universe.

As noted by the CERN Courier — the news magazine of the CERN Laboratory in Geneva, which hosts the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest science experiment — more than 250 scientists from 30 countries presented more than 200 talks on a multitude of subjects relevant to experimental and theoretical research. SMU physicists presented at the conference.

The SMU organizing committee was led by Fred Olness, professor and chair of the SMU Department of Physics in Dedman College, who also gave opening and closing remarks at the conference. The committee consisted of other SMU faculty, including Jodi Cooley, associate professor; Simon Dalley, senior lecturer; Robert Kehoe, professor; Pavel Nadolsky, associate professor, who also presented progress on experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider; Randy Scalise, senior lecturer; and Stephen Sekula, associate professor.

Sekula also organized a series of short talks for the public about physics and the big questions that face us as we try to understand our universe.

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks

Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse

Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health

Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach

Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach

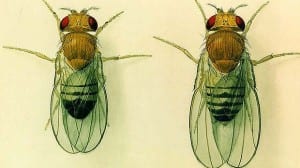

Fruit flies fed organic diets are healthier than flies fed nonorganic diets, study finds

Fruit flies fed organic diets are healthier than flies fed nonorganic diets, study finds Center for Creative Leadership to study innovative learning method of SMU Lyle School of Engineering

Center for Creative Leadership to study innovative learning method of SMU Lyle School of Engineering Parenting program tackles child abuse and neglect among formerly homeless families

Parenting program tackles child abuse and neglect among formerly homeless families