A simple cognitive task as early as four days after a brain injury activates the region that improves memory function, and may guard against developing depression or anxiety

Concern is growing about the danger of sports-related concussions and their long-term impact on athletes. But physicians and healthcare providers acknowledge that the science is evolving, leaving questions about rehabilitation and treatment options.

Currently, guidelines recommend that traumatic brain injury patients get plenty of rest and avoid physical and cognitive activity until symptoms subside.

But a new pilot study looking at athletes with concussions suggests total inactivity may not be the best way to recover after all, say scientists at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, where the research was conducted.

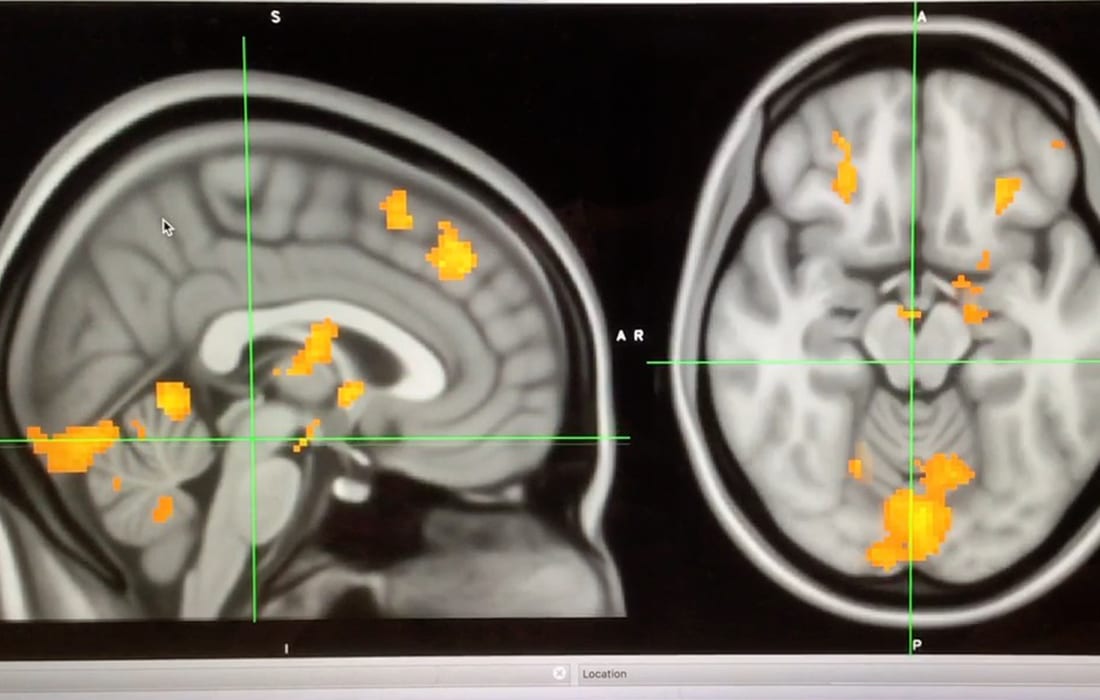

The study found that a simple cognitive task as early as four days after a brain injury activated the region that improves memory function and can guard against two hallmarks of concussion — depression and anxiety.

“Right now, if you have a concussion the directive is to have complete physical and cognitive rest, no activities, no social interaction, to let your brain rest and recover from the energy crisis as a result of the injury,” said SMU physiologist Sushmita Purkayastha, who led the research, which was funded by the Texas Institute for Brain Injury and Repair at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

“But what we saw, the student athletes came in on approximately the third day of their concussion and the test was not stressful for them. None of the patients complained about any symptom aggravation as a result of the task. Their parasympathetic nervous system — which regulates automatic responses such as heart rate when the body is at rest — was activated, which is a good sign,” said Purkayastha, an assistant professor in the Department of Applied Physiology and Wellness.

The parasympathetic nervous system is associated with better memory function and implicated in better cardiovascular function. It also helps to regulates stress, depression and anxiety — and those are very common symptoms after a concussion.

“People in the absolute rest phase after concussion often experience depression,” Purkayastha added. “In the case of concussion, cutting people off from their social circle when we say ‘no screen time’ — particularly the young generation with their cell phones and iPads — they will just get more depressed and anxious. So maybe we need to rethink current rehabilitation strategy.”

The new study addresses the lack of research upon which to develop science- and data-based treatment for concussion. The findings emerged when the research team measured variations in heart rate variability among athletes with concussions while responding to simple problem-solving and decision-making tasks.

While we normally think of our heart rate as a steady phenomenon, in actuality the interval varies and is somewhat irregular — and that is desirable and healthy. High heart rate variability is an indicator of sound cardiovascular health. Higher levels of variability indicate that physiological processes are better controlled and functioning as they should, such as during stressful (both physical and challenging mental tasks) or emotional situations.

Concussed athletes normally have lowered heart rate variability.

For the new study, Purkayastha and her team administered a fairly simple cognitive task to athletes with concussions. During the task, the athletes recorded a significant increase in heart rate variability.

The study is the first of its kind to examine heart rate variability in college athletes with concussions during a cognitive task.

The findings suggest that a small measure of brain work could be beneficial, said co-investigator and neuro-rehabilitation specialist Kathleen R. Bell, a physician at UT Southwestern.

“This type of research will change fundamentally the way that patients with sports and other concussions are treated,” said Bell, who works with brain injury patients and is Chair of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at UT Southwestern. “Understanding the basic physiology of brain injury and repair is the key to enhancing recovery for our young people after concussion.”

The researchers reported their findings in the peer-reviewed Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, in the article “Reduced resting and increased elevation of heart rate variability with cognitive task performance in concussed athletes.”

Co-authors from SMU Simmons School include Mu Huang and Justin Frantz; Peter F. Davis and Scott L. Davis, from SMU’s Department of Applied Physiology and Wellness; Gilbert Moralez, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, Dallas; and Tonia Sabo, UT Southwestern.

Concussion symptom improved with simple brain activity

Volunteer subjects for the study were 46 NCAA Division I and recreational athletes who participate in contact-collision sports. Of those, 23 had a physician-diagnosed sports-related concussion in accordance with NCAA diagnostic criteria. Each of them underwent the research testing within approximately three to four days after their injury.

Not surprisingly, compared to the athletes in the control group who didn’t have concussions, the athletes with concussions entered answers that were largely incorrect.

More importantly, though, the researchers observed a positive physiological response to the task in the form of increased heart rate variability, said Purkayastha.

“It’s true that the concussed group gave wrong answers for the most part. More important, however, is the fact that during the task their heart rate variability improved,” she said. “That was most likely due to the enhancement of their brain activity, which led to better regulation. It seems that engaging in a cognitive task is crucial for recovery.”

Heart rate variability is a normal physiological process of the heart. It makes possible a testing method as noninvasive as taking a patient’s blood pressure, pulse or temperature. In the clinical field, measuring heart rate variability is an increasingly common screening tool to see if involuntary responses in the body are functioning and being regulated properly by the autonomic nervous system.

The parasympathetic is blunted or dampened by concussion

Abnormal fluctuations in heart rate variability are associated with certain conditions before symptoms are otherwise noticeable.

Monitoring heart rate variability measures the normal synchronized contractions of the heart’s atriums and ventricles in response to natural electrical impulses that rhythmically move across the muscles of the heart.

After a concussion, an abnormal and unhealthy decline in heart rate variability is observed in the parasympathetic nervous system, a branch of the autonomic nervous system. The parasympathetic is in effect blunted or dampened after a concussion, said Purkayastha.

As expected, in the current study, heart rate variability was lower among the athletes with concussions than those without.

New findings add evidence suggesting experts rethink rehab

But that changed during the simple cognitive task. For the athletes with concussions, their heart rate variability increased, indicating the parasympathetic nervous system was activated by the task.

Heart rate variability between the concussed and the controls was comparable during the cognitive task, the researchers said in their study.

“This suggests that maybe we need to rethink rehabilitation after someone has a concussion,” Purkayastha said. — Margaret Allen, SMU