July 20, Candace Walkington, an associate professor and Gerald J. Ford Research Fellow in the Simmons School of Education and Human Development at SMU Dallas, for a piece advocating that math curriculum be more compelling and relevant to modern day applications and career needs. Published in the Austin American-Statesman under the heading The way Texas teaches math just doesn’t add up: https://bit.ly/3xWSn27

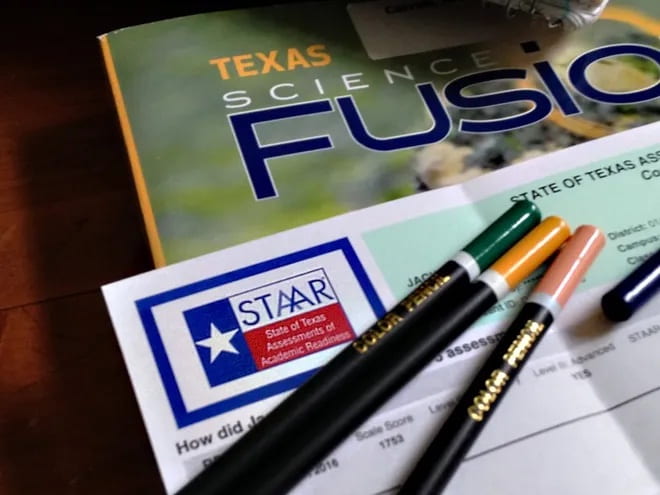

Recent headlines highlight the “deep learning loss” in Texas schools over the past school year, particularly in mathematics. Reports link this situation to students who attended school virtually all year – due to the pandemic – as those who “lost” the most. STAAR math results show many students in 5th and 8th grades are not meeting standards.

Why is engaging in virtual learning associated with a drop in math scores? There are a lot of complex issues surrounding why students score as they do on standardized tests, but the recent comparisons are useful for highlighting the incredibly problematic way in which math is taught in our schools in Texas.

Mathematics is typically taught in middle and high school as an endless series of demonstration and practice. Students are tasked with watching the teacher and copying what they do, often performing rote procedures that they do not understand. They are taught to sit quietly and follow instructions, as they solve sets of boring, decontextualized problems. Math is not taught in a compelling way, and students are expected to simply accept this.

By Candace Walkington

Recent headlines highlight the “deep learning loss” in Texas schools over the past school year, particularly in mathematics. Reports link this situation to students who attended school virtually all year – due to the pandemic – as those who “lost” the most. STAAR math results show many students in 5th and 8th grades are not meeting standards.

Why is engaging in virtual learning associated with a drop in math scores? There are a lot of complex issues surrounding why students score as they do on standardized tests, but the recent comparisons are useful for highlighting the incredibly problematic way in which math is taught in our schools in Texas.

Mathematics is typically taught in middle and high school as an endless series of demonstration and practice. Students are tasked with watching the teacher and copying what they do, often performing rote procedures that they do not understand. They are taught to sit quietly and follow instructions, as they solve sets of boring, decontextualized problems. Math is not taught in a compelling way, and students are expected to simply accept this.

When students are given these tasks during in-person learning, they have little choice but to comply. But virtual learning changes this dynamic —when students are joining remotely, getting students to do work that is simply not interesting is a lot harder. Suddenly, math has to compete with everything else. And it is important to acknowledge that this “everything else” that school math has been competing with is not a waste of students’ time. Students have learned all sorts of new skills and ways of interacting during the pandemic.

One way to address these issues with mathematics instruction and to accelerate learning is to seize the opportunity offered by the pandemic to reset the way math is taught. We can make math compelling and applicable to real-life situations. Math can be made meaningful by connecting to students’ communities and worlds, to their career interests and other interests, to hands-on experiences, and by giving learners choice and control over their math learning.

Recent advances in technologies also offer myriad ways to make math captivating – from having students do modeling activities in Desmos or GeoGebra, to engaging students with Augmented or Virtual Reality technologies, to utilizing motion capture, geospatial, or gesture-based mobile technologies, to having students learn math through video games.

The pandemic has made it clear that the way we have been teaching math is not working. Many students do not want to learn math in the traditional way, and they shouldn’t have to. This type of math does not connect to students’ lives and experiences, and does not empower them or show them the ways math is used to model and understand the world.

Practically speaking, many of the things students are learning in school math won’t have application later in life. There is disconnect between the math taught in school and the really important math used in careers and in society. For example, our research on the work of STEM professionals shows that they are not sitting in their workplace solving the quadratic formula, simplifying polynomials or factoring.

Schools need to reconsider the kinds of math curricula and technology they are using and implement programs that allow students to explore deeply relevant math using new technologies (e.g., GeoGebra’s Illustrative Mathematics). They also need to invest in teacher training in strategies like mathematical modeling, authentic problem-solving, game-based learning, and project-based learning. And legislators and leaders need to rethink the math standards themselves, by considering what 21st-century skills students will actually need for the post-pandemic world.

Candace Walkington is an associate professor and Gerald J. Ford Research Fellow in the Simmons School of Education and Human Development at SMU Dallas.