The past six days have been a whirlwind. It’s amazing that one can be so exhausted after sitting down at a desk for 7 hours of the day. Our arrival on Monday certainly captured the essence of DC. We were immediately thrown into a metro full of suits and ties. Truly seeing Capitol Hill for the first time was quite impressive. The weather was brisk but comfortable when the triad of the Capitol, Court, and Libraries all came into view as we ascended the escalator from the Capitol South metro stop.

The past six days have been a whirlwind. It’s amazing that one can be so exhausted after sitting down at a desk for 7 hours of the day. Our arrival on Monday certainly captured the essence of DC. We were immediately thrown into a metro full of suits and ties. Truly seeing Capitol Hill for the first time was quite impressive. The weather was brisk but comfortable when the triad of the Capitol, Court, and Libraries all came into view as we ascended the escalator from the Capitol South metro stop.

Day one consisted of acquiring our very own library cards, and touring the House and Senate. Tuesday was welcomed with the anticipation that comes with the first real research day. Immediately feelings of unpreparedness came over me when I second guessed the cases I wanted to call forward. But after a moment of panic I regained collection, and filled out my first call slip of many to come. Wednesday was somewhat of an emotional rollercoaster between feelings of glee and frustration.

On Thursday we ventured out to the Court and experienced the pomp and circumstance that lies outside the Manuscript Reading Room. Friday and Saturday consisted of grabbing those final boxes and rechecking to make sure all my notes and scans were in order for the trip home early tomorrow morning.

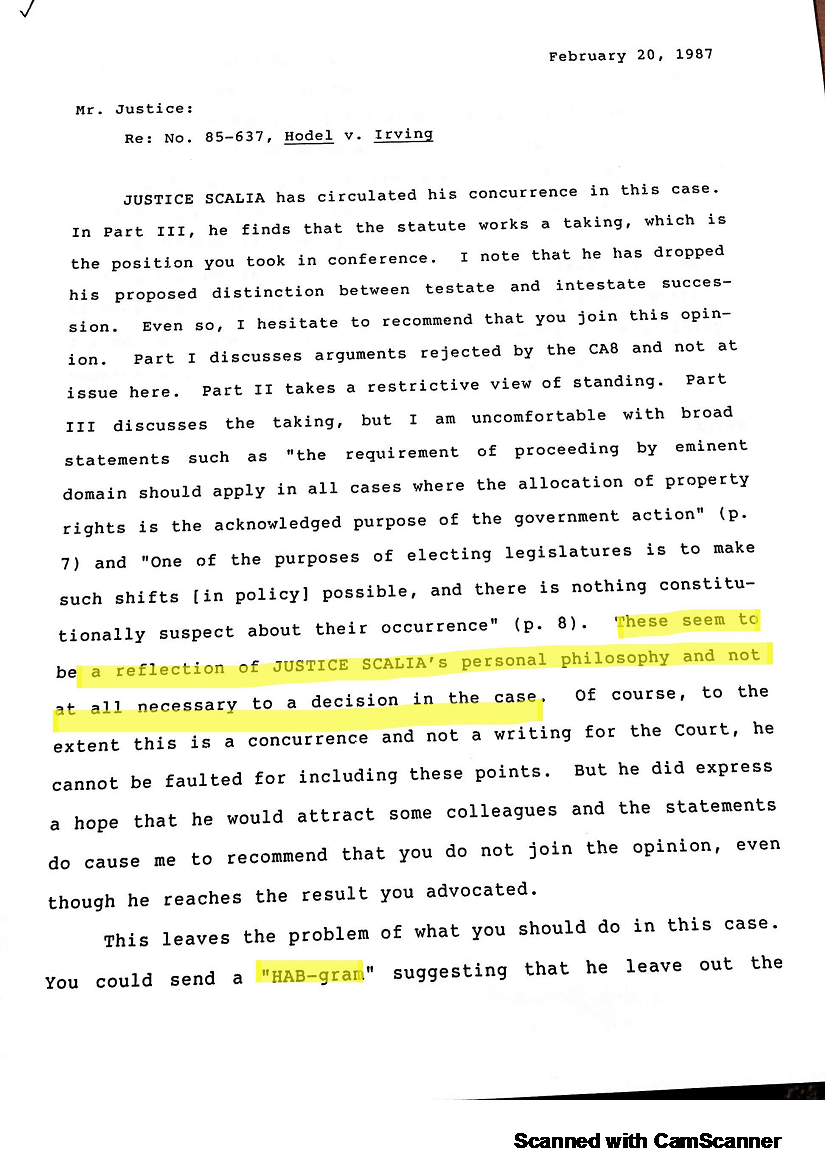

Behind every small moment of discovery was two hours of decoding handwriting, comparing draft opinions, and getting distracted by clerk gossip and court peculiarities. In the case below, Justice Blackmun’s clerk accuses Justice Scalia of arbitrarily involving his personal views in the case opinion. Additionally, at the bottom of the page, he advises Justice Blackmun to pen a “HAB-gram” to suggest changes (Harry A. Blackmun). I laughed when I came across the amusing nickname for Justice Blackmun’s memos.

Oftentimes the cases I expected to be filled with drama and bargaining simply weren’t. It’s weird to accept that what is in that file is all that’s left of the decision-making process. Some cases had fewer memos and comments than others, which made it difficult to glean any significant conclusions. Those are the moments when I really remember that I am working with primary documents; in those moments when history is missing, and will never be uncovered. In the digital era, there is an expectation that we can find anything on the internet we could possibly need. While digitization of the justices papers has begun, currently they are still only fully accessible in person. Additionally, even if the case file is uploaded, sometimes the information just isn’t there.

Those moments of realization probed larger methodological questions about understanding the past through preservation of artifacts. On Saturday, our final day in DC and at the Library of Congress, the head archivist, Jeff Flannery, gave us a private tour of some of the backrooms where the archives were stored. It was heartwarming to see his excitement about his role in preserving America’s national treasures. He showed us a recipe sent to George Washington about how to prepare beaver nuggets. And on a more topical note, we saw a letter from young Barack Obama declining a clerkship from Justice Brennan. We concluded that Barack Obama probably made a good decision. While walking through the files we were surprised to see a sign that asked employees to call the Capitol police if a water leak was spotted. Once again, I was reminded of the fragility of the documents, and the surrealness of the opportunity to work with them.The limited nature of historical preservation also led me to question the relationship between political scientists and the judiciary. What judges think they do, and what political scientists say judges do are two very different things. In some sense, judges have an active interest in hiding what they do from the public and academia. Justice White’s papers disappointed most of the class because they lacked any personal memos. He was known for culling through his papers before releasing them to the Library. To a degree, political scientists and the justices work in opposition to one another. A molecule can’t question the biologist that inquires into the nature of its functioning. But Justices are human, and humans can be skeptical and defensive. While going through the papers I would assume the mindset of a detective attempting to get to the bottom of a certain Justice’s vote despite the limited evidence before me.

I come away from the week with the recognition that there are few undergraduate experiences when students truly get to do political science, rather than just learn about it … and this is one of them.

![Typed page: Re: No. 85-637, Hodel v. Irving; JUSTICE SCALIA has circulated his concurrence in this case. In Part III, he finds that the statue works a taking, which is the position you took in conference. I note that he has dropped his proposed distinction between testate and intestate succsession. Even so, I hesitate to recommend that you join this opinion. Part I discusses arguments rejected by the CA8 and not at issue here. Part II takes a restrictive view of standing. Part III discusses the taking, but I am uncomfortable with broad statements such as "the requirement of proceeding by eminent domain should apply in all cases where the allocation of property rights is the acknowledged purpose of the government action" (p. 7) and "One of the purposes of electing legislatures is to make such sifts (in policy) possible, and there is nothing constitutionally suspect about their occurrence" (p. 8). [Highlighted] These seem to be a reflection of JUSTICE SCALIA's personal philosophy and not at all necessary to a decision in the case. [End Highlighted] Of course, to the extent that this is a concurrence and not a writing for the Court, he cannot be faulted for including these points. But he did not express a hope that he would attract some colleagues and the statements do cause me to recommend that you do not join the opinion, even though he reaches the result you advocated. This leaves the problem of what you should do in this case. You could send a [Highlighted "HAB-gram"] suggesting that he leave out the...](https://blog.smu.edu/honors-courses/files/2019/04/Megan-Hauk-Hodel-v-Irving-1vho7di-212x300.png)