It’s hard to believe that just 6 days ago, we flew here to begin our research. On the plane ride over, I was anxious for the journey ahead. There was no precedent in my experience for anything like this. Professor Kobylka had often said that we would be “making scholarship rather than just consuming scholarship.” How can I, a second year undergraduate, produce anything that can even be compared to the academic work of the professors that teach me? It’s a task that is hard to imagine. Yet, our professor has confidence in us, and he never even gives off the impression that he is afraid we will fail. When he sees us falter, he is there with encouragement. On my first day in the library, I was freaking out. How are these pages supposed to tell me something about how these people think? It seemed like an exercise in futility.

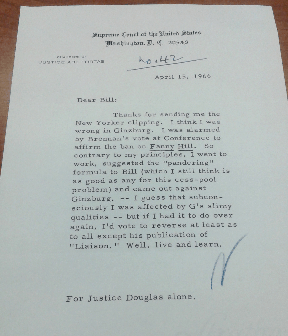

However, after doing it for some time, I began to see patterns. I can form a chronology of the events of a case. See who joins. See who leaves. See what someone said must go in and what must come out. I am not looking at someone interpret it for me. I am actually getting a cross section into looking at these things happen myself. Looking at the papers of the justices causes you to feel like you begin to know them. The humanity of the individual flows through the pages. The justices, though they are people with an immensely important solemn duty in the functioning of our republic, at the end of the day are people just like you and me. They are conscious of how their decisions will affect all of us, and it is often a struggle for them to decide things. For example, Justice Abe Fortas, in a private memo to Justice William Brennan, laments his vote in Ginzburg v. United States . Fortas’ admission is no small deal; he is recognizing that in a decision that was 5-4, because of his personal vote, a man is serving a 5 year sentence for the way he advertised a product, and future decisions will be based on this as well. Justices are faced with tough decisions the same way all of us are with the sobering understanding that their decisions will be looked at for the rest of history.In the process I am watching unfold, the justices are trying to create a consistent and pragmatic standard for obscenity, a class of speech that the Court determined should not be protected by the First Amendment. I chose this topic because I wondered what their reasoning could be in drawing this conclusion, and what basis they could make for differentiating that which is obscene and that which is not. I expected to see some sort of high minded reasoning and airtight logic. But it would make more sense to say that’s exactly what I didn’t find. The justices can all agree what they have doesn’t work, but they can make no consensus on what will. I recall a memo in which one justice puts the situation in terms I never would have imagined seeing: It is more important that whatever standard they come up with work than be fair. The justices, like all of us, must balance values and make a decision that will elate some and crush others. But it is a job that they understood going into it. The Constitution and its values do not all agree, because there is not one vision at the center. It is an attempt to put all of the best visions together, even when they don’t agree. And as John Marshall said, “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is” and resolve these problems.

![Typed memo on Justice Fortas' personal stationary dated 4/15/1966: Dear Bill: Thanks for handing me the New Yorker clipping. I think I was wrong in [Glaxbarg?]. I was [indistinguishable word] by Brennan's vote at Conference to affirm the ban on Fanny Hill. So contrary to [indistinguishable word] principles. I want to work, suggested the "pundering" formula to Bioll (which I still think is as good as any for this cess-pool problem) and came out against Ginsburg. -- I guess that [indistinguishable word] I was affected by G's slimy qualities -- but if I had it to do over again, I'd vote to reverse at least as to all except his publication of '[Lisisun?.]' Well, live and learn, [Signed "N"]; For Justice Douglas alone.](https://blog.smu.edu/honors-courses/files/2019/04/Grayson-Sumpter-Memo-Fortas-to-Brennan-1nsiuq6-e1554834781762-257x300.png)