SMU Dedman School of Law Prof. Chris Jenks visited Naval Station Guantanamo Aug. 11-15. This is the fifth and final blog of the series.

SMU Dedman School of Law Prof. Chris Jenks visited Naval Station Guantanamo Aug. 11-15. This is the fifth and final blog of the series.

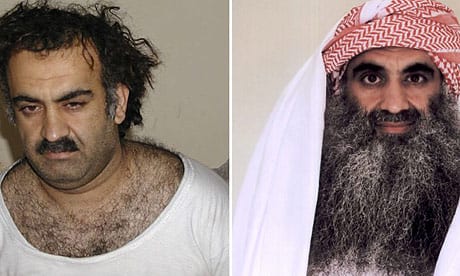

Ostensibly I traveled to Gitmo to observe the military commission proceedings against five members of al-Qaeda who allegedly planned the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks. Included among them is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who once boasted, “I was responsible for the 9/11 operation from A to Z.”

Mohammed has undergone a radical transformation. And since spring 2012, he’s been dying much of his beard henna-red, as shown here.

I say “ostensibly” because although the military commission was to be in session Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., we were in court a total of six hours. For the week.

The only thing I saw accomplished was that the military judge reconsidered an earlier ruling he’d made to break the case of one of the 9/11 planners away from the other four. As a result, all five are back in one joint 9/11 case, which is another way of saying the case has returned to square zero.

It’s difficult to convey all the time and effort that goes into having the prosecution, defense, translators, analysts, etc., at Gitmo. And the security involved in moving someone like Mohammed and the other 9/11 planners is what you would expect: A massive undertaking that basically shuts down the entire place. Yet when everyone is present in court and there’s an opportunity to resolve issues and move toward a trial, little, if any, progress is made.

I didn’t talk with the victims’ families. I don’t know what their expectations or goals were in traveling there. But if it was to achieve some kind of closure, they have to have left bewildered and disappointed.

I didn’t talk with the victims’ families. I don’t know what their expectations or goals were in traveling there. But if it was to achieve some kind of closure, they have to have left bewildered and disappointed.

The question everyone asks is why is this taking so long? The short answer is that this is the largest case in U.S. criminal justice history, with 2,779 victims and hundreds of thousands of documents, witnesses and evidence across many continents. Also consider that while only a small percentage of the evidence is classified, that’s a small percentage of hundreds of thousands of documents. That’s a lot of classified documents. Add to that the manner by which the U.S. government determines what information is classified: Put mildly, said process is quirky, cumbersome and slow.

Another oft-asked question is why military commissions? Military commissions fill a space between traditional military courts-martial and federal court trials. The exigencies of combat limit the ability of the military to collect and process evidence in a way that would be admissible in a traditional setting.

For instance, if four U.S. Army soldiers in Afghanistan capture a member of al-Qaida you can expect they’ll immediately try to question him while pointing loaded weapons at him. That’s simply a battlefield reality and necessity. Admittedly, pointing a weapon at someone while yelling a series of questions is coercive, and likely not admissible at a courts-martial or federal court. In addition, the manner in which the soldiers collect evidence is not as rigorous as the FBI and CSI.

But some Gitmo detainees were captured by the FBI or CIA, not the military. In some minds that undermines the rationale of military commissions. To others, the issue of who is captured where doesn’t matter: the U.S. is fighting members of al-Qaida wherever it finds them.

A key factor in all this is the manner in which the U.S. treated some of the detainees — a manner that went well beyond the inherent coercion of battlefield capture and questioning. As President Obama recently acknowledged, “We tortured some folks.” And if the actions didn’t constitute torture, they may have included cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment (CIDT), which violates the Geneva Conventions.

As President Obama recently acknowledged, “We tortured some folks.” And if the actions didn’t constitute torture, they may have included cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment (CIDT), which violates the Geneva Conventions.

It’s unclear how the military commission will account for the accused 9/11 planners potentially having been tortured. It’s important to know that military commission rules don’t allow the government to use, directly or indirectly, any statement obtained through torture or CIDT. A notable result of that: What would have been a joint 9/11 trial of six al-Qaida members is now a trial of five.

The U.S. treatment of the sixth accused 9/11 planner, Mohammed al-Qatani (who purportedly tried to be the 20th hijacker), included severe isolation, exposure to cold, sleep deprivation and forced nudity — all of which, according to the U.S. government, left him in a “life-threatening situation.” Given that, and the fact that most of the evidence against al-Qatani was the product of torture or CIDT, the U.S. decided to not send his case to trial.

We’re reminded of this awkward fact by how the military commissions’ courtroom is outfitted within the $12 million Expeditionary Legal Complex. When the courtroom was built, the plan was to have the 9/11 trial include al-Qatani. Thus there are six defense tables, with one left conspicuously empty.

Our group, including members of the media, non-governmental organizations and 9/11 victims’ family members, witness the proceedings in a small sound-proofed room separated by a clear partition at the back of the courtroom. Though a couple of TV monitors allow us to see the proceedings in real-time, the most challenging aspect of observing the commissions is, for security reasons, having to get the audio on a 40-second delay.

While we’re there, four of the five 9/11 planners on trial are wearing head scarves in support of Palestine in the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We watch a weird moment unfold during a break, when one of the accused offers an extra headscarf to the planner not wearing one. A lot of confused gesturing unfolds across the defense tables, leading some in our group to liken it to a situation in which one person obviously didn’t get the company’s dress memo.

We also see that 9/11 planner has several detailed military defense counsel, as well as “learned counsel” — an attorney experienced in death penalty cases.

By the week’s end the military judge recessed the commission until October. It’s unclear whether the next time it convenes the proceedings will transpire any differently than what we’ve observed. If history is any indication, the answer is, unfortunately, no. Like Sisyphus, doomed to perpetually push the same boulder up the same hill every day, there’s a kind of “road to perdition” aspect to all this.

When we weren’t in court (which was the vast majority of time), we met with counsel for both the defense as well as the prosecution, and both were very generous with their time. We also sat in on two press conferences. This reminds me of my largest takeaway from the week: How press conference content is delivered and how the media seems to perceive and process it.

As it stands now, the defense and their attorneys, who are arguing for liberty and American values, are in sole position of the moral high ground, despite the fact they are representing individuals alleged to have killed nearly 3,000 people.

As it stands now, the defense and their attorneys, who are arguing for liberty and American values, are in sole position of the moral high ground, despite the fact they are representing individuals alleged to have killed nearly 3,000 people.

When not discussing the detainees’ trial and/or treatment, we have time to take in the setting. The water around Gitmo is amazing, with two and three different shades of blue. In the absence of a city setting, the skies at night are filled with stars, and with a certain type of plankton in the water there, it almost looks like fireflies are dancing under water. But then the reality of where we are returns.

During the day, our escorts continue to drive us around Gitmo — mostly to the dining facility or navy exchange store. We meet locals who talk about what a safe place Gitmo is for raising a family, which is an odd thought, especially as I see a little girl, eyes beaming, leave the exchange with a new doll. Afterward we pass green energy sources while traveling to meet with a defense counselor in an office of the Gitmo gym. It occurs to me then that Gitmo is an onion of sorts, with layer upon layer of the surreal.

Despite the time and cost expended on this place thus far, the American people don’t realize the commissions really haven’t even started. They don’t realize how much more is still to come, how long that will take and how expensive it will be, at least if detention and commissions remain at Gitmo.

Despite the time and cost expended on this place thus far, the American people don’t realize the commissions really haven’t even started. They don’t realize how much more is still to come, how long that will take and how expensive it will be, at least if detention and commissions remain at Gitmo.

For example, the 9/11 trial won’t be for at least another year. Then, the appeals that are certain to follow will take more than a decade. Now consider that the detainee population at Gitmo ranges from as young as 30 to as old as 67. That means that the U.S. may be detaining members of al-Qaida for 50 years to come. And at a staggering cost.

According to recent government reports, the cost per year to operate just the detention facilities at Gitmo is $454 million a year (and so far has cost the U.S. more than $5 billion). That breaks down to $2.7 million per detainee per year. Compare that to the roughly $78,000 a year to incarcerate someone in a maximum security prison in the U.S.

In anticipation of increasing medical needs of the aging detainees, the Department of Defense is requesting about $11 million for a medical facility best equipped to offer geriatric care for aging al-Qaida members from now until beyond 2050.

Does the U.S. really want to continue down that path? And, more important, does it even recognize the path it’s on? — C.J.