Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Peter Weyand in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Related links

- Peter Weyand

- Journal of Applied Physiology: “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up”

- Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development

More SMU Research news

Canada’s National Post newspaper quotes SMU’s Peter Weyand, an expert in human locomotion, in an Aug. 8 article “Five things: The trials and tribulations of Oscar ‘Blade Runner’ Pistorius”

The Post article examines the controversy surrounding double-amputee sprinter Oscar Pistorius. Preparing now for the 2012 London Olympics, the 24-year-old South African once again is under the spotlight for his controversial carbon-fiber prosthetic legs that attach just below his knees.

Weyand is widely quoted in the press for his expertise on human speed. He led a team of scientists who are experts in biomechanics and physiology in conducting experiments on Oscar Pistorius and the mechanics of his racing ability. Pistorius has made headlines worldwide trying to qualify for races against runners with intact limbs, including the Olympics.

Weyand is an SMU associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics in the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development.

EXCERPT:

National Post

South African double amputee Oscar Pistorius was chosen to run in the 400 metres and 4x400m relay at the world athletics championships later this month. Here are five things to know before the big race in Daegu, South Korea.1. His legs are better than your legs

Known as the ‘Blade Runner’ and the ‘Fastest man with no legs,’ Pistorius had both legs amputated below the knee for medical reasons when he was 11 months old.He uses high-tech carbon-fibre blades in competition, with spikes on the forefoot for the track. The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) began to monitor his races in the 2007 to analyze his technique and determine if he had an advantage.

“The company does make bionic feet that have hydraulics and are battery powered but this is a passive foot,” Pistorius told the Daily Telegraph in 2007. “That means that the output energy is not as much as the input energy so it definitely does not give me an unfair advantage.”

2. But they don’t come cheap

In a 2007 Wired feature on Pistorius’ attempt to qualify for the 2008 Olympics, the magazine says each leg costs between $15,000 (US) and $18,000 (US). It’s a small price to pay for an Olympic dream, considering the custom-made Cheetah Flex-Foot blades are made to look like human legs.It also explains why Pistorius insists on taking the prosthetic legs in his carry-on luggage when he flies, especially after one incident in the United States. “I went to run in Atlanta and my legs ended up in Salt Lake City,” he tells the Telegraph.

3. He’s had trouble with the IAAF

Pistorius first competed against able-bodied athletes in 2007 but the IAAF then amended its rules to ban the use of “any technical device that incorporates springs, wheels or any other element that provides a user with an advantage over another athlete not using such a device.”In the following year the world governing body said scientific research had shown Pistorius enjoyed an advantage over able-bodied athletes and banned him from competitions held under their rules.

However, the decision was overruled by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, making Pistorius eligible for the 2008 Beijing although he was unable to qualify for the South African team, winning gold medals instead in the Paralympic 100, 200 and 400 meters.

4. And then there’s the ’10-second advantage’

The question of whether Mr. Pistorius’ artificial limbs artificially enhance his running speeds is a matter of scientific disagreement. Two researchers who studied Pistorius, Drs. Matthew Bundle and Peter Weyand, conclude that his artificial limbs enhance his sprint running performances by 15-30% over his intact limb competitors. Their findings were published in the Journal of Applied Physiology in 2009.SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

New York Times: As Debate Goes On, Amputee Will Break Barrier

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date August 9, 2011

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Peter Weyand in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu.

Related links

- Peter Weyand

- Journal of Applied Physiology: “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up”

- Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development

More SMU Research news

The New York Times tapped the expertise of SMU’s Peter Weyand, an expert in human locomotion, in an Aug. 8 article “As Debate Goes On, Amputee Will Break Barrier”

Journalist Juliet Macur examines the controversy surrounding double-amputee sprinter Oscar Pistorius. Preparing now for the 2012 London Olympics, the 24-year-old South African once again is under the spotlight for his controversial carbon-fiber prosthetic legs that attach just below his knees.

Weyand is widely quoted in the press for his expertise on human speed. He led a team of scientists who are experts in biomechanics and physiology in conducting experiments on Oscar Pistorius and the mechanics of his racing ability. Pistorius has made headlines worldwide trying to qualify for races against runners with intact limbs, including the Olympics.

Weyand is an SMU associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics in the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development.

EXCERPT:

By Juliet Macur

The New York Times

The moment that the sprinter Oscar Pistorius had hoped for and trained for finally came Monday when he was named to South Africa’s team for the track and field world championships, which will make him the first amputee to compete at the event.“If I manage to make it through the heats, I would be thrilled.” Oscar Pistorius, on qualifying for the world championships.

Pistorius, a four-time Paralympic champion, will race in the 400 meters and the 4×400 relay against men who have two natural legs, while he uses prosthetics. Last month, he ran fast enough to meet the Olympic qualifying standard, and now he will blaze a trail.

“This will be the highest-profile and most prestigious able-bodied event which I have ever competed in, and I will face the highest caliber of athletes from across the planet,” Pistorius, 24, said in a statement sent Monday by his agent, Peet van Zyl. “If I manage to make it through the heats, I would be thrilled.”

The road to the world championships could just lead to a berth in the 2012 London Games for Pistorius, who said he had never considered himself disabled and had never considered the world championships or Olympics out of his reach.

Even so, that road to making the team for this month’s world championships, which will begin Aug. 27 in Daegu, South Korea, has not been smooth for Pistorius — and his road to the Olympics may not be any smoother.

Born without his fibulas, the long bones that span from the knees to the ankles, Pistorius relies on carbon-fiber prosthetic limbs to propel him around the track in times comparable to some of the world’s top runners. And therein remains the question that has been the crux of a continuing debate: do those high-tech legs give him an unfair advantage?

In 2008, the International Association of Athletics Federations, track and field’s governing body, thought so. It ruled that Pistorius was ineligible to compete in the worlds because his prosthetic legs made it easier for him to run than competitors with legs made of flesh and bone. But he appealed to the Court of Arbitration for Sport and won in May 2008.

The court, though, provided no definitive answer to the underlying question of whether Pistorius was naturally fast or just fast because of his prosthetic legs. It said that the I.A.A.F. failed to meet its burden of proving that Pistorius’s legs provided him with an overall advantage or disadvantage.

To further complicate the issue, the court made it clear that the case could be reopened, saying that advances in technology and a different testing regime might prove that Pistorious’s legs did, in fact, give him an edge.

“There was a disagreement among the scientists, but I feel that the conclusion was overwhelming that he’s a lot faster with the legs than someone is without them,” said Peter Weyand, an associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics at Southern Methodist University and one of seven scientists who in 2008 conducted physiological and biomechanical tests on Pistorius at Rice University.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

ESPN: The Olympics loom for Oscar Pistorius

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date August 5, 2011

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Peter Weyand in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Related links

- Peter Weyand

- Journal of Applied Physiology: “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up”

- Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development

More SMU Research news

Sports journalist Johnette Howard quotes SMU’s Peter Weyand, an expert in human locomotion, in an Aug. 5 article “The Olympics loom for Oscar Pistorius”

Howard examines the accomplishments of double-amputee sprinter Oscar Pistorius and the controversy that has dogged his racing career. Preparing now for the 2012 London Olympics, the 24-year-old South African once again is under the spotlight for his controversial carbon-fiber prosthetic legs that attach just below his knees.

Weyand is widely quoted in the press for his expertise on human speed. He led a team of scientists who are experts in biomechanics and physiology in conducting experiments on Oscar Pistorius and the mechanics of his racing ability. Pistorius has made headlines worldwide trying to qualify for races against runners with intact limbs, including the Olympics.

Weyand is an SMU associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics in the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development.

EXCERPT:

By Johnette Howard

ESPN

You hope the murmuring and arguing that has already restarted now that Oscar Pistorius has done the remarkable, the extraordinary, the heretofore unfathomable will not drag him down between now and the 2012 London Olympics. Because what Pistorius, a double-amputee sprinter, was able to do on a muggy night in Lignano, Italy, on July 19 is the sort of mind-blowing achievement that shouldn’t be unfairly derailed by this unsettled debate. He thought he had already navigated it once, but now it’s likely to trail the 24-year-old South African all the way to next year’s Olympic Summer Games. [ … ]Perhaps the most contentious assertion, Peter Weyand, an associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics at Southern Methodist University, and Matthew Bundle, now an assistant professor at the University of Montana, have argued that, among other things, Pistorius enjoys as much as a 10 to 12 second advantage in a 400-meter race using his prosthetic legs, for reasons Weyand says have to do with the frequency of how quickly Pistorius is able reposition his lightweight legs as he strides; the force he exerts; the longer length of time each of his prosthetic feet remains on the ground; and reduced ground force requirements to attain the same sprinting speeds.

“You can collect more data, but the answers about Oscar Pistorius are in, in my opinion,” Weyand said in a phone interview Tuesday. “He is able to run faster than many of his competitors even though he does not hit the ground as hard.”

To which Hugh Herr of MIT, another member of the Pistorius research group, retorts, “It baffles me why Weyand and Bundle continue to say that.”

Herr, an associate professor and director of MIT’s biomechatronics research group, argues, “You really have to have rigorous, peer-reviewed, published, carefully examined scientific evidence. [Weyand-Bundle’s argument] is simply a calculation, nearly a back-of-the-envelope calculation. To label it as a scientific study is very misleading. ??? Their calculation was never published in a peer-reviewed paper. It was in the point/counterpoint article, which was not rigorously peer-reviewed.”

So the debate about Pistorius lives on. But how much does it still matter?

Other than perhaps inhibiting his training — as the IAAF controversy and CAS fight did back in 2008, when he admitted it dragged him down emotionally (“It’s been completely on this kid’s back to prove everything himself so he can run,” Mullins says) — the griping needn’t stop him.

“As far as we are concerned, the CAS decision is final and the case is closed, as long as he continues to compete on the same prosthetic legs the CAS ruled on,” insisted Jeffrey Kessler, the New York-based attorney who took on Pistorius’ case on a pro bono basis and represents the National Basketball Player’s Association and NFL Players Association in their labor negotiations. “I spoke to Oscar on the phone the other day and I’ve committed to him that when he runs in London, I will be there. To me, this is about the rights of the disabled. He is one of the most inspiring people I’ve ever met in my life.”

Weyand has been careful to stress that he admires Pistorius, too, and finds the man and his accomplishments “absolutely extraordinary.” But Weyand considers himself just a scientist doing his job, and added that nothing he has asserted, “should in any way diminish what Oscar has done.”

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

ESPN Grantland: Is the Fastest Human Ever Already Alive?

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date July 14, 2011

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Peter Weyand in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu. |

Related links

- Peter Weyand

- Journal of Applied Physiology: “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up”

- Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development

More SMU Research news

Sports journalist Chuck Klosterman quotes SMU’s Peter Weyand, an expert in human locomotion, in the July 12 article “Is the Fastest Human Ever Already Alive?”

Klosterman looks at the evolution of track’s 100-meter dash and runners’ repeated shattering of the world record for the race. In discussing the mechanics of human speed, he quotes Weyand on how it relates to a runner’s physiology and the force sprinter’s apply to the ground.

Weyand, who is widely quoted in the press for his expertise on human speed, is an SMU associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics in the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development.

He led a team of experts in biomechanics and physiology that conducted experiments on Oscar Pistorius, a South African bilateral amputee track athlete. Pistorius has made headlines trying to qualify for races against runners with intact limbs, including the Olympics.

EXCERPT:

By Chuck Klosterman

ESPN Grantland

Allow me to spare you the hyperbole: Usain Bolt is fast.He is, as far as we can tell, the fastest human who’s ever lived — in 2009, at a race in Berlin, he ran the 100-meter dash is 9.58 seconds. This translates to an average speed of just over 23 mph (with a top speed closer to 30 mph). His ’09 performance in Germany was .11 quicker than the 9.69 he ran at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the fattest chunk ever taken off a world record at that distance. Considering the unadulterated simplicity of his vocation and the historic magnitude of his dominance, it’s easy to argue that Bolt has been the world’s greatest athlete of the past five years. And yet there’s an even easier argument to make than that one: Within the next 10 years, Bolt’s achievements as a sprinter will be completely annihilated.

This is not guaranteed, of course, but it’s certainly more plausible than speculative — for the past 30 years, the men’s record in the 100-meter dash has been assaulted so continually that many of its former record holders don’t even qualify as difficult answers to trivia questions. This was not always the case: Jim Hines broke the 10.0 barrier with a 9.95 at the (high-altitude) 1968 Olympics; that mark stood for 15 years before Calvin Smith ran a 9.93 (also at altitude) in Colorado Springs. But since 1983, the record has been shattered more than a dozen times. Ben Johnson’s steroid-fueled 9.83 in ’87 was the first massive blow, but eight others have chipped away at the record with increasing regularity (Bolt just happened to use a sledge hammer). …

… “The scientific understanding of sprinting is pretty immature,” concedes Peter Weyand, and — since Weyand has become the de facto American expert on the science of sprinting — that tells you just how mysterious this phenomenon is. A physiologist and biomechanist at Southern Methodist University, Weyand specializes in terrestrial locomotion; while at Harvard in the ’90s, he directed experiments at Concord Field Station, a facility where researchers regularly placed animals such as cheetahs,1 wolverines, and kangaroos on treadmills to understand the mechanics of movement. Now 50, Weyand was also a fairly swift runner in his younger days, having run the 100-yard dash in 10.8 as a high school student. “The one thing about sprinting we all understand is that speed comes from how hard the runner’s foot hits the ground. Someone like Bolt is hitting the ground with 1,000 pounds of force, and we just don’t how he does that. For example, we have a very accurate understanding of how much weight someone can lift — we can take a person’s frame and his muscle mass and accurately estimate how much weight he’ll be able to bench press. But world-class sprinters deliver twice as much force as our estimates indicate, and we don’t know why.”

Discovery News: Why walking is harder for smaller people

- Post author By Margaret Allen

- Post date November 17, 2010

A Nov. 15 article on Discovery News cites the research of SMU physiologist and biomechanist Peter Weyand in which he and other scientists found that everyone uses about the same amount of energy when they walk, but short people use more energy over a given distance. The reason: people with shorter legs take more steps to cover the same distance as people with longer legs.

Weyand says the study has clinical applications and weight balance applications. In addition, the military is interested too because metabolic rates influence the physiological status of soldiers in the field, he said.

Also covering the research is MSNBC with the story Take that, Stretch! Short people burn more calories walking, and UPI, with its story Equation calculates energy cost of walking.

Weyand is an SMU associate professor of applied physiology and biomechanics in the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development. He led a team of experts in biomechanics and physiology that conducted experiments on Oscar Pistorius, a South African bilateral amputee track athlete. Pistorius has made headlines trying to qualify for races against runners with intact limbs, including the Olympics.

Excerpt:

By Liz Day

Discovery News

Why do children tire more quickly than adults when out for a walk?Like most people who have had to carry a tired child home after a long walk, Peter Weyand of Southern Methodist University asked himself that same question. Scientists had long recognized that smaller people use more energy per kilogram body mass than larger individuals when walking.

He wanted to know why.

The reason smaller people use more energy is not due to a different gait or a less efficient metabolic rate per stride. The key was something simpler: their height.

Smaller people tire faster because they take more steps to cover the same distance or travel the same steps as taller people. Their strides are shorter.

Weyand teamed up with three other researchers to study the issue. Their findings are published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

To test the cost of walking, the team measured the metabolic rates of children and adults. Participants ranged from 5 to 32 years old, from 35 to 195 lbs and from 3’6 to a little over 6 feet tall.

The volunteers were filmed walking on treadmills. Their oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were measured to gauge their metabolic rate.

The team compared their walks too — measuring their strides, the way they walked, stride durations and the proportion of each stride spent in contact with the ground.

Results showed everyone moved in the exact same way, no matter if they were 4 feet or 6 feet tall. Analysis also found that everyone used the same amount of energy per stride, regardless of height. So, the energy discrepancy was not due to the style of walking.

Finally, the researchers plotted walkers’ heights against their minimum energy expenditure. The results excited them. The walkers’ energy costs were almost perfectly inversely proportional to their heights. Ergo, tall people walk more economically because they have longer strides and take fewer steps to cover the same distance.

Book a live interview

To book a live or taped interview with Peter Weyand in the SMU News Broadcast Studio call SMU News at 214-768-7650 or email news@smu.edu.

Related links

- Peter Weyand

- Journal of Applied Physiology: “The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up”

- Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education & Human Development

More SMU Research news

Evidence weak for tropical rainforest 65 million years ago in Africa’s low-latitudes

Veterinary medicine shifts to more women, fewer men; pattern will repeat in medicine, law fields

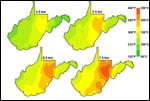

SMU Geothermal Lab: Large, green energy source in West Va. coal country

No evidence for ancient comet causing Clovis catastrophe, archaeologists say

DOD, industry fund $5.6 million SMU-led research for hi-tech prosthetics