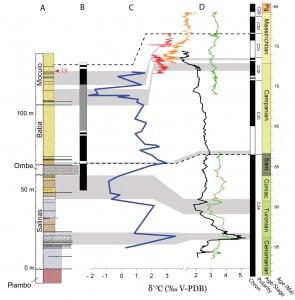

Uplift and aridification of East Africa causing changes in vegetation has been considered a driver of human evolution. Now a fossil whale stranded far inland in Kenya marks the first time scientists can pinpoint how many millions of years ago the uplift began.

Uplift associated with the Great Rift Valley of East Africa and the environmental changes it produced have puzzled scientists for decades. Timing and starting elevation have been poorly understood.

Now paleontologists have tapped a fossil from the most precisely dated beaked whale in the world to pinpoint for the first time a date when East Africa’s mysterious elevation began. The stranded whale is the only one ever found so far inland on the African continent.

The 17 million-year-old fossil is from the beaked Ziphiidae whale family. It was discovered 740 kilometers inland at a elevation of 620 meters in modern Kenya’s harsh desert region, said vertebrate paleontologist Louis L. Jacobs, Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

At the time the whale was alive, it would have been swimming far inland up a river with a low gradient ranging from 24 to 37 meters over more than 600 to 900 kilometers, said Jacobs, a co-author of the study.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides the first constraint on the start of uplift of East African terrain from near sea level.

“The whale was stranded up river at a time when east Africa was at sea level and was covered with forest and jungle,” Jacobs said. “As that part of the continent rose up, that caused the climate to become drier and drier. So over millions of years, forest gave way to grasslands. Primates evolved to adapt to grasslands and dry country. And that’s when — in human evolution — the primates started to walk upright.”

Identified as a Turkana ziphiid, the whale would have lived in the open ocean, like its modern beaked cousins. Ziphiids, still one of the ocean’s top predators, are the deepest diving air-breathing mammals alive, plunging to nearly 10,000 feet to feed, primarily on squid.

In contrast to most whale fossils, which have been discovered in marine rocks, Kenya’s beached whale was found in river deposits, known as fluvial sediments, said Jacobs, a professor in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences of SMU’s Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences.

The ancient large Anza River flowed in a southeastward direction to the Indian Ocean.

The whale, probably disoriented, swam into the river and could not change its course, continuing well inland.

“You don’t usually find whales so far inland,” Jacobs said. “Many of the known beaked whale fossils are dredged by fishermen from the bottom of the sea.”

Determining ancient land elevation is very difficult, but the whale provides one near sea level.

“It’s rare to get a paleo-elevation,” Jacobs said, noting only one other in East Africa, determined from a lava flow.

Beaked whale fossil surfaced after going missing for more than 30 years

The beaked whale fossil was discovered in 1964 by J.G. Mead in what is now the Turkana region of northwest Kenya.

Mead, an undergraduate student at Yale University at the time, made a career at the Smithsonian Institution, from which he recently retired. Over the years, the Kenya whale fossil went missing in storage. Jacobs, who was at one time head of the Division of Paleontology for the National Museums of Kenya, spent 30 years trying to locate the fossil. His effort paid off in 2011, when he rediscovered it at Harvard University and returned it to the National Museums of Kenya.

The fossil is only a small portion of the whale, which Mead originally estimated was 7 meters long during its life. Mead unearthed the beak portion of the skull, 2.6 feet long and 1.8 feet wide, specifically the maxillae and premaxillae, the bones that form the upper jaw and palate.

The researchers reported their findings in “A 17-My-old whale constrains onset of uplift and climate change in east Africa” online at the PNAS web site.

Modern cases of stranded whales have been recorded in the Thames River in London, swimming up a gradient of 2 meters over 70 kilometers; the Columbia River in Washington state, a gradient of 6 meters over 161 kilometers; the Sacramento River in California, a gradient of 4 meters over 133 kilometers; and the Amazon River in Brazil, a gradient of 1 meter over 1,000 kilometers.

Besides Jacobs, other authors from SMU are Andrew Lin, Michael J. Polcyn, Dale A. Winkler and Matthew Clemens.

From other institutions, authors are Henry Wichura and Manfred R. Strecker, University of Potsdam, and Fredrick K. Manthi, National Museums of Kenya.

Funding for the research came from SMU’s Institute for the Study of Earth and Man and the SMU Engaged Learning program. — Margaret Allen

Follow SMUResearch.com on twitter at @smuresearch.

SMU is a nationally ranked private university in Dallas founded 100 years ago. Today, SMU enrolls nearly 11,000 students who benefit from the academic opportunities and international reach of seven degree-granting schools. For more information see www.smu.edu.

SMU has an uplink facility located on campus for live TV, radio, or online interviews. To speak with an SMU expert or book an SMU guest in the studio, call SMU News & Communications at 214-768-7650.

Study will teach algebra with student-authored stories that draw on their own interests

Study will teach algebra with student-authored stories that draw on their own interests Hunt begins for elusive neutrino particle at one of the world’s largest, most powerful detectors

Hunt begins for elusive neutrino particle at one of the world’s largest, most powerful detectors Key to speed? Elite sprinters are unlike other athletes — deliver forceful punch to ground

Key to speed? Elite sprinters are unlike other athletes — deliver forceful punch to ground Hunt for dark matter takes physicists deep below earth’s surface, where WIMPS can’t hide

Hunt for dark matter takes physicists deep below earth’s surface, where WIMPS can’t hide Marital tension between mom and dad can harm each parent’s bond with child, study finds

Marital tension between mom and dad can harm each parent’s bond with child, study finds Booming mobile-health app market needs robust FDA oversight to ensure consumer safety, confidence

Booming mobile-health app market needs robust FDA oversight to ensure consumer safety, confidence

Comet theory false; doesn’t explain cold snap at the end of the Ice Age, Clovis changes or mass animal extinction

Comet theory false; doesn’t explain cold snap at the end of the Ice Age, Clovis changes or mass animal extinction Real-time audio of corporal punishment shows kids misbehave within 10 minutes of spanking

Real-time audio of corporal punishment shows kids misbehave within 10 minutes of spanking Conventional vs. modern: Repertoire drives opera house identity, market share

Conventional vs. modern: Repertoire drives opera house identity, market share Women have made strides for equality in society, but gender gap still exists in art museum directorships

Women have made strides for equality in society, but gender gap still exists in art museum directorships Search for dark matter covers new ground with CDMS experiment in Minnesota

Search for dark matter covers new ground with CDMS experiment in Minnesota NOvA experiment glimpses neutrinos, one of nature’s most abundant, and elusive particles

NOvA experiment glimpses neutrinos, one of nature’s most abundant, and elusive particles SMU scientists to deploy seismic monitors in North Texas region near Azle, Texas

SMU scientists to deploy seismic monitors in North Texas region near Azle, Texas The research of an international paleontological team working in Angola and co-led by SMU paleontologist

The research of an international paleontological team working in Angola and co-led by SMU paleontologist  The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks

Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse

Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health

Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach

Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach Musicians who learn a new melody demonstrate enhanced skill after a night’s sleep

Musicians who learn a new melody demonstrate enhanced skill after a night’s sleep

Study: Most Texas ISDs that are teaching the Bible are skirting 2007 state law

Study: Most Texas ISDs that are teaching the Bible are skirting 2007 state law Study finds Jurassic ecosystems were similar to modern: Animals flourish among lush plants

Study finds Jurassic ecosystems were similar to modern: Animals flourish among lush plants SMU contributes fossils, expertise to new Perot Museum in ongoing scientific collaboration

SMU contributes fossils, expertise to new Perot Museum in ongoing scientific collaboration 100 million-year-old coelacanth discovered in Texas is new fish species from Cretaceous

100 million-year-old coelacanth discovered in Texas is new fish species from Cretaceous Academic achievement improved among students active in structured after-school programs

Academic achievement improved among students active in structured after-school programs Texas frontier scientists who uncovered state’s fossil history had role in epic Bone Wars

Texas frontier scientists who uncovered state’s fossil history had role in epic Bone Wars