New launch of the world’s most powerful particle accelerator is the most stringent test yet of our accepted theories of how subatomic particles work and interact.

Start up of the world’s largest science experiment is underway — with protons traveling in opposite directions at almost the speed of light in the deep underground tunnel called the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva.

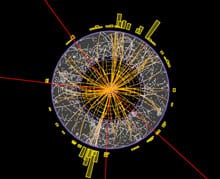

As protons collide, physicists will peer into the resulting particle showers for new discoveries about the universe, said Ryszard Stroynowski, a collaborator on one of the collider’s key experiments and a professor in the Department of Physics at Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

“The hoopla and enthusiastic articles generated by discovery of the Higgs boson two years ago left an impression among many people that we have succeeded, we are done, we understand everything,” said Stroynowski, who is the senior member of SMU’s Large Hadron Collider team. “The reality is far from this. The only thing that we have found is that Higgs exist and therefore the Higgs mechanism of generating the mass of fundamental particles is possible.”

There is much more to be learned during Run 2 of the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

“In a way we kicked a can down the road because we still do not have sufficient precision to know where to look for the really, really new physics that is suggested by astronomical observations,” he said. “The observed facts that are not explained by current theory are many.”

The LHC’s control room in Geneva on April 5 restarted the Large Hadron Collider. A project of CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, the 17-mile LHC tunnel — big enough to ride a bicycle through — straddles the border between France and Switzerland.

Two years ago it made headlines worldwide when its global collaboration of thousands of scientists discovered the Higgs Boson fundamental particle.

The Large Hadron Collider’s first run began in 2009. In 2012 it was paused for an extensive upgrade.

The new upgraded and supercharged LHC restarts at almost twice the energy and higher intensity than it was operating at previously, so it will deliver much more data.

“I think that in the LHC Run 2 we will sieve through more data than in all particle physics experiments in the world together for the past 50 years,” Stroynowski said. “Nature would be really strange if we do not find something new.”

SMU is active on the LHC’s ATLAS detector experiment

Within the big LHC tunnel, gigantic particle detectors at four interaction points along the ring record the proton collisions that are generated when the beams collide.

In routine operation, protons make 11,245 laps of the LHC per second — producing up to 1 billion collisions per second. With that many collisions, each detector captures collision events 40 million times each second.

That’s a lot of collision data, says SMU physicist Robert Kehoe, a member of the ATLAS particle detector experiment with Stroynowski and other SMU physicists.

Evaluating that much data isn’t humanly possible, so a computerized ATLAS hardware “trigger system” grabs the data, makes a fast evaluation, decides if it might hold something of interest to physicists, than quickly discards or saves it.

“That gets rid of 99.999 percent of the data,” Kehoe said. “This trigger hardware system makes measurements — but they are very crude, fast and primitive.”

To further pare down the data, a custom-designed software program culls even more data from each nano-second grab, reducing 40 million events down to 200.

Two groups from SMU, one led by Kehoe, helped develop software to monitor the performance of the trigger systems’ thousands of computer processors.

“The software program has to be accurate in deciding which 200 to keep. We must be very careful that it’s the right 200 — the 200 that might tell us more about the Higgs boson, for example. If it’s not the right 200, then we can’t achieve our scientific goals.”

The ATLAS computers are part of CERN’s computing center, which stores more than 30 petabytes of data from the LHC experiments every year, the equivalent of 1.2 million Blu-ray discs.

Flood of data from ATLAS transmitted via tiny electronics designed at SMU to withstand harsh conditions

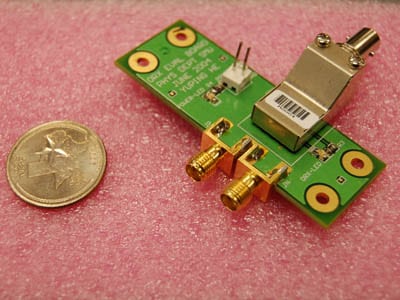

An SMU physics team also collaborates on the design, construction and delivery of the ATLAS “readout” system — an electronic system within the ATLAS trigger system that sends collision data from ATLAS to its data processing farm.

Data from the ATLAS particle detector’s Liquid Argon Calorimeter is transmitted via 1,524 small fiber-optic transmitters. A powerful and reliable workhorse, the link is one of thousands of critical components on the LHC that contributed to discovery and precision measurement of the Higgs boson.

The custom-made high-speed data transmitters were designed to withstand extremely harsh conditions — low temperature and high radiation.

“It’s not always a smooth ride operating electronics in such a harsh environment,” said Jingbo Ye, the physics professor who leads the SMU data-link team. “Failure of any transmitter results in the loss of a chunk of valuable data. We’re working to improve the design for future detectors because by 2017 and 2018, the existing optical data-link design won’t be able to carry all the data.”

Each electrical-to-optical and optical-to-electrical signal converter transmits 1.6 gigabytes of data per second. Lighter and smaller than their widely used commercial counterpart, the tiny, wickedly fast transmitters have been transmitting from the Liquid Argon Calorimeter for about 10 years.

Upgraded optical data link is now in the works to accommodate beefed-up data flow

A more powerful data link — much smaller and faster than the current one — is in research and development now. Slated for installation in 2017, it has the capacity to deliver 5.2 gigabytes of data per second.

The new link’s design has been even more challenging than the first, Ye said. It has a smaller footprint than the first, but handles more data, while at the same time maintaining the existing power supply and heat exchanger now in the ATLAS detector.

The link will have the highest data density in the world of any data link based on the transmitter optical subassembly TOSA, a standard industrial package, Ye said.

Fine-tuning the new, upgraded machine will take several weeks

The world’s most powerful machine for smashing protons together will require some “tuning” before physicists from around the world are ready to take data, said Stephen Sekula, a researcher on ATLAS and assistant professor of physics at SMU.

The trick is to get reliable, stable beams that can remain in collision state for 8 to 12 to 24 hours at a time, so that the particle physicists working on the experiments, who prize stability, will be satisfied with the quality of the beam conditions being delivered to them, Sekula said.

“The LHC isn’t a toaster,” he said. “We’re not stamping thousands of them out of a factory every day, there’s only one of them on the planet and when you upgrade it it’s a new piece of equipment with new idiosyncrasies, so there’s no guarantee it will behave as it did before.”

Machine physicists at CERN must learn the nuances of the upgraded machine, he said. The beam must be stable, so physicists on shifts in the control room can take high-quality data under stable operating conditions.

The process will take weeks, Sekula said.

10 times as many Higgs particles means a flood of data to sift for gems

LHC Run 2 will collide particles at a staggering 13 teraelectronvolts (TeV), which is 60 percent higher than any accelerator has achieved before.

“On paper, Run 2 will give us four times more data than we took on Run 1,” Sekula said. “But each of those multiples of data are actually worth more. Because not only are we going to take more collisions, we’re going to do it at a higher energy. When you do more collisions and you do them at a higher energy, the rate at which you make Higgs Bosons goes way up. We’re going to get 10 times more Higgs than we did in run 1 — at least.”

SMU’s ManeFrame supercomputer plays a key role in helping physicists from the Large Hadron Collider experiments. One of the fastest academic supercomputers in the nation, it allows physicists at SMU and around the world to sift through the flood of data, quickly analyze massive amounts of information, and deliver results to the collaborating scientists.

During Run 1, the LHC delivered about 8,500 Higgs particles a week to the scientists, but also delivered a huge number of other kinds of particles that have to be sifted away to find the Higgs particles. Run 2 will make 10 times that, Sekula said. “So they’ll rain from the sky. And with more Higgs, we’ll have an easier time sifting the gems out of the gravel.”

Run 2 will operate at the energy originally intended for Run 1, which was initially stalled by a faulty electrical connection on some superconducting magnets in a sector of the tunnel. Machine physicists were able to get the machine running — just never at full power. And still the Higgs was discovered, notes SMU physics professor Fredrick Olness.

“The 2008 magnet accident at the LHC underscores just how complex a machine this is,” Olness said. “We are pushing the technology to the cutting-edge.”

Huge possibilities for new discoveries, but some will be more important than others

There are a handful of major new discoveries that could emerge from Run 2 data, Stroynowski said.

- New physics laws related to Higgs — Physicists know only global Higgs properties, many with very poor understanding. They will be measuring Higgs properties with much greater precision, and any deviation from the present picture will indicate new physics laws. “Improved precision is the only guaranteed outcome of the coming run,” Stroynowski said. “But of course we hope that not everything will be as expected. Any deviation may be due to supersymmetry or something completely new.”

- Why basic particles have such a huge range of masses — Clarity achieved by precision measurements of Higgs properties may help to shed light on the exact reason for the pattern of masses found in the known fundamental particles. If new particles are discovered in the LHC during Run 2, the mathematical theories that could explain them might also shed light on the puzzle of why masses have such diversity in the building blocks of nature

- Dark matter — Astronomical observations require a new form of matter that acts only via gravity, otherwise all galaxies would have fallen apart a long time ago. One candidate theory is supersymmetry, which predicts a host of new particles. Some of those particles, if they exist, would fit the characteristics of dark matter. LHC scientists will be looking for them in the coming run both directly, and for indirect effects.

- Quark gluon plasma — In collisions of lead nuclei with each other, LHC scientists have observed a new form of matter called quark gluon plasma. Thought to have been present in the cosmos near the very beginning of time, making and studying this state of matter could teach us more about the early, hot, dense universe.

- Mini black-holes — Some scientists are looking for “mini black-holes” predicted by innovative physicist Stephen Hawking, but that is considered “a v-e-e-e-e-r-y long shot,” Stroynowski said.

- Matter-antimatter — A cosmic imbalance in the amounts of matter and its opposite, antimatter, must be explained by particle physics. The LHC is home to several experiments and teams that aim to search for answers.

— SMU, Fermilab, CERN

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music

The Undying Radio: Familiarity breeds content when it comes to listeners and music Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks

Mosquito indexing system identifies best time to act against potential West Nile Virus outbreaks Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse

Sweden, SMU psychologists partner to launch parenting program that reduces child abuse Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health

Chemical probe confirms that body makes its own rotten egg gas, H2S, to benefit health Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach

Study: High-volume Bitcoin exchanges less likely to fail, but more likely to suffer breach Musicians who learn a new melody demonstrate enhanced skill after a night’s sleep

Musicians who learn a new melody demonstrate enhanced skill after a night’s sleep Study finds that newlyweds who are satisfied with marriage are more likely to gain weight

Study finds that newlyweds who are satisfied with marriage are more likely to gain weight Fruit flies fed organic diets are healthier than flies fed nonorganic diets, study finds

Fruit flies fed organic diets are healthier than flies fed nonorganic diets, study finds Center for Creative Leadership to study innovative learning method of SMU Lyle School of Engineering

Center for Creative Leadership to study innovative learning method of SMU Lyle School of Engineering NOvA neutrino detector in Minnesota records first 3-D particle tracks in search to understand universe

NOvA neutrino detector in Minnesota records first 3-D particle tracks in search to understand universe Parenting program tackles child abuse and neglect among formerly homeless families

Parenting program tackles child abuse and neglect among formerly homeless families Hiding in plain sight: How invisibility saved New Mexico’s Jicarilla Apache

Hiding in plain sight: How invisibility saved New Mexico’s Jicarilla Apache Study: Most Texas ISDs that are teaching the Bible are skirting 2007 state law

Study: Most Texas ISDs that are teaching the Bible are skirting 2007 state law

Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance

Human diabetes has new research tool: Overfed fruit flies that develop insulin resistance Moving 3D computer model of key human protein is powerful new tool in fight against cancer

Moving 3D computer model of key human protein is powerful new tool in fight against cancer Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual

Ancient tree-ring records from southwest U.S. suggest today’s megafires are truly unusual Middle school boys who are reluctant readers value reading more after using e-readers

Middle school boys who are reluctant readers value reading more after using e-readers Dark matter search may turn up evidence of WIMPS: SMU Researcher Q&A

Dark matter search may turn up evidence of WIMPS: SMU Researcher Q&A